A Portrait of Japanese Immigrants

On covering First Generation Japanese Immigrants / ARAMASA Taku

In the autumn of 1980, a relative with whom my family had lost contact in the former Japanese colony of Manchuria suddenly returned to Japan temporarily for the first time in 35 years. This event stirred me very much emotionally. This relative’s name had already been carved into a Buddhist mortuary tablet, so her homecoming caused both great surprise and joy to my entire extended family. Witnessing this event also profoundly filled me with the desire to understand the feelings of Japanese who have permanently distanced themselves from their homeland. I had a hunch that attaining such comprehension might turn out to be the most important work I ever did.

I wonder if it is correct to say that I am a Japanese and that Japan is my motherland simply because I was born and brought up on this island nation. All that really means is that I possess Japanese citizenship, but it has little significance otherwise. I think of myself as an international person in the true sense precisely because I have my roots firmly planted in the unique culture of Japan which was fostered and transmitted by my ancestors. This small, ordinary matter is something I have started to think about sometimes during breaks in the commercial filming I do as my regular profession.

I wonder if it is correct to say that I am a Japanese and that Japan is my motherland simply because I was born and brought up on this island nation. All that really means is that I possess Japanese citizenship, but it has little significance otherwise. I think of myself as an international person in the true sense precisely because I have my roots firmly planted in the unique culture of Japan which was fostered and transmitted by my ancestors. This small, ordinary matter is something I have started to think about sometimes during breaks in the commercial filming I do as my regular profession.

I began to wonder if I could not make a follow-up by myself on the earliest immigrants who moved faraway from Japan in the Meiji Period (1868-1912). I privately concluded that working on this theme would detonate my gradually growing concern about the existence that is know as “Japanese," and that it would also give me the optimum chance to re-inspect the Japanese intently from an outside position.

I read up avidly on the history of Japanese immigration from around the fall of 1983 to the end of February, 1984. After gathering as many materials and doing as much preliminary research as possible on the Japanese in South America, North America, and Hawaii, I decided to focus on the people still living who had boarded the Kasato-Maru, the first immigration boat to Brazil.

Then in March, 1984, I visited São Paulo for a month, where I immediately carried out a survey locally, and managed to meet with the final eight survivors. In São Paulo I ran into some strange happenings, such as finding out that 95 year old Naoe Sonoda from Kagoshima Prefecture, who was reported to be dead at that point, was actually alive. On the other hand, 93 year old Ushi Ishibaru, originally from Okinawa, died on the very day I was scheduled to interview her.

The survey undertaken locally struck with a force that would be impossible in a report based on materials collected on a desk. By meeting with the eight living witnesses, I managed to conjure up a clear image of the Kasato-Maru, which had not been much more than a phantom in my mind before I left Tokyo.

This preliminary survey, furthermore, helped me form a hazy image of the feelings of the Japanese who had permanently distanced themselves faraway from their homeland. Then finally in July of the same year I went to Brazil once more, this time all prepared to work in earnest. In any case, I ended up spending the rest of 1984 searching out the earliest immigrants to various parts of South America for this photo reportage. I feel that, as a result,

I have been able to grasp in my own way the tide of the earliest Japanese immigration to South American countries. I also realized that I should probably polish and perfect my art by gazing at things from a spot of tranquility with a quiet point of view. I hope to be able to work with "seeing” by taking a re-look at my own self via a natural body, while I express my relationship with the subject openly.

I arrived via Kobe at the Yokohama Immigration Center. The eye doctor there gave me a really strict examination, and I was also given a talk by settlement company on what I should know about the immigration ship and the settlement area, and so on. Three days later I headed for Peru on the French ship, Caravelas. They gave me 120 yen for my boat fare. I put the 20 yen I saved from that into my waist band.

We entered the port of Callao 45 days later in the month of November. By the time I reached the Cikitoi settlement for which I was contracted, I had been cheated by Japanese gamblers, and struck by a degenerate sailor-turned thief ; so that I lost all my money.

At the plantation I was sent to, I was treated like virtually no more than a slave, and again cheated out of my wages. Then a fever started going around, and after a half of year I finally escaped from the plantation narrowly with just my life, and went on to Lima.

I managed to subsist for a year as a waiter, meanwhile picking up the language. During that time I managed to save up something toward travelling expenses, and crossed the Andes on foot. I also worked as a waiter for about a half of a year in the vicinity of Cusco.

Since it would be impossible to return to Japan draped in silver brocades by working as a waiter, I got a job with Inca Rubber, and went into the rubber mountain of Tambopata.

I saved up an adequate amount after working there over a year, so I moved down the Tambopata River to Puerto Maldonado, where there about 50 Japanese residents. And there was even one Japanese woman. That made me both happy and strangely nostalgic.

Afterwards I got wind of a most appealing job offer. So several of us young men gathered to put together a raft with driftwood. We floated along the Madre de Dios River for over 20 days before arriving in Riberalta.”

This precious living record of Japanese immigration to South America was related to me by 96 year old Bunkichi Kamikubo (p. 124), who presently resides in Florencia Varella, a suburb of Buenos Aires. His amazing memory recalls the professional story tellers of the past, and he certainly did not sound like someone over 90.

Riberalta lies in the northern extreme of Bolivia close to the Brazilian border near the source of the Amazon. This region is well known within the history of Japanese immigration for the many incidents involving rubber which broke out around the 40th year of the Meiji Period (1907). To borrow a term from Kazuo Ito's Overseas Japanese, this became the terminal station for the "wandering immigrants” from Peru. Mr. Kamikubo continued to explain recall :

There I slept with a red-haired Bolivian woman for the first time, Then I worked furiously for two years, and managed to send 2000 ven back to Japan. My folks in Kagoshima apparently built a house with that money.

After five years in Riberalta, I moved down the Amazon into Brazil. I arrived in Belém via Manaus in 1927. From there I moved on once more via São Paulo to Argentina. I'm finally settled now, and I'm satisfied where I am. A person doesn't really get fixed in a place until the birth of a grandchild.”

To the very end, Mr. Kamikubo never spoke about his homeland.

"Huh, you want to hear about Japanese bloodlines? About Japanese blood, huh?

Well the idea of having blue-eyed grandchildren has become a reality for us, you see.

A ravine forms a stream, which, in turn, becomes a river. And ultimately even the greatest river – even the Amazon — will turn into the sea. So, you see, Japanese blood runs into a great ocean here!"

This is an excerpt from a conversation I had with 75 year old Katsuo Uchiyama (p. 158), currently the managing editor of a São Paulo newspaper company. In 1930, Uchiyama went to Brazil as an immigrant farmer sharing a room on the same boat with the late author Tatsuzo Ishikawa.

Is silk thread still spun in Fukushima nowadays? The morning dew on the mulberry leaves must be swished away first.”

Umeno Tadano (p. 89) spoke to me in a gentle Fukushima dialect. She had not returned to her native country in the 76 years since she moved to Brazil. I met her in Iguape in the state of São Paulo. Just two days after I got her story and photographs, she died peacefully, as if in a deep sleep. She was 101 years old.

This comment came from 84 year old Kan-ichi Takeshita (p. 94), a man who immigrated to South America on his own accord, and is said to be the first of the “issei” (first generation) to marry a non-Japanese. Takeshita and his physically weak wife led a quiet life together in São Paulo, translating the dialogue of Shochiku movies like the “Tora-san” series into Portuguese.

women. Birth and death occasionally came together. The 'sansei' and 'yonsei' (fourth generation) are very lucky because nowadays proper hospitals exist here in Peru.” This is what I heard from 87 year old Chidori Kuroiwa (p. 96, 97), an expert midwife now living in the Casilla section of Lima. There are said to be just under 80,000 people of Japanese descent in Peru, and Ms. Kuroiwa helped deliver some 4,700 of them.

But the 'sansei' and 'yonsei' leave even this dear settlement to go off to the cities to find a job; and then they become fancy clerks and the like. So is this why we of the first generation worked so hard to put our descendents into college ?”

The above is an excerpt from a conversation I had with 84 year old Zenji Watanabe (p. 29, 66), a pioneer Japanese settler living in Colonia Esperanca in the state of Parana.

This was related to me in a pleasant tone by 86 year old Masuno Kanazawa (p. 136) in La Colmena, Paraguay. Power transmission lines had been opened up in recent years in La Colmena, so refrigerators and the like are now in use in the city. Therefore, it is no longer a problem to make ice pillows for people who have suddenly taken ill. The highway to the capital has also been paved, so that “Colmena Fuji” can now be reached within three hours from Asuncion. Vigorous activity was being carried out by the local Agricultural Collective in the fifteenth year since its founding.

Masuno's homemade red miso (soy bean) paste with a tantalizingly sharp malt fragrance and her unrefined soy grains (moromi) were simply out of this world. It may seem a bit ironic that I received some to take back to Japan as a souvenir.

This is what 75 year old Nario Komaki told to me about his mother Karu, who had just died on June 2, 1984, at age 94. Karu had originally immigrated to Brazil on Kasato-Maru before moving on to Argentina. I took a commemorative photograph of Nario (p. 125) in front of his mother's grave in Tucuman, about 1,200 kilometers to the north of Buenos Aires.

I really waited a long time to receive a passport from the country. The boat fare was expensive, so I sneaked on. Yes, I was a stowaway. In those days there were occasionally stowaways like myself. I worked on the boat, and then ran away at a port which took my fancy. When I ventured from Valparaiso, Chile to Peru, I had absolutely no trouble even without a proper visa since the Bolivian border guard was so loose. I have a true Yamato (native Japanese) spirit !” said 86 year old Sadao Matsumoto (p. 121) when I took his photograph in Valle de la Luna in the suburbs of La Paz, Bolivia.

Human beings should not live amidst contradictions and complications forever. Furthermore, even when they are feeling homesick, immigrants can not exactly ignore the real life they have. An immigrant will start feeling comfortable once he comes to have affection and a sense of responsibility toward the land where he is actually residing.

The descendants of the first immigrants are now growing up as Brazilians. They go against the wishes of their ‘issei' parents and guardians to marry the natives, and/or to participate as local people in student and various other political movements.”

The aforementioned excerpt was quoted from the voluminous History of Immigrant Life with the permission of its author, Tomoo Handa (p. 99), a 79 year old painter who lives in Sao Paulo.

I must say that I was rather amazed to hear modest-sounding expressions like “exposing my decrepitness” in Brazil when they are in the process of dying out in Japan these days. Ise Hayashi is the younger sister of the late great novelist Jun-ichiro Tanizaki. Born in Kakigara-cho, Nihombashi, the heart of traditional Tokyo, she spoke with a pure, crisp Edo accent that still remains in my ears.

Ninety-two year old Fukumoto, also known as Donpanchito, was one of the earliest immigrants to Riberalta along the Beni River in Bolivia. However he was unable to forget Puerto Maldonado, and is now the only one left of the immigrants who moved back there. “Donpanchito” is an honorary title given to him by the local residents.

Yoshimitsu Nakamura (p. 146), the 72 year old Chairman of the Japanese Society of Bauru in the state of Sao Paulo, made the brief comment, “I only finally reached the decision to be buried here in Brazil when I held my blue-eyed grandchildren for the first time.”

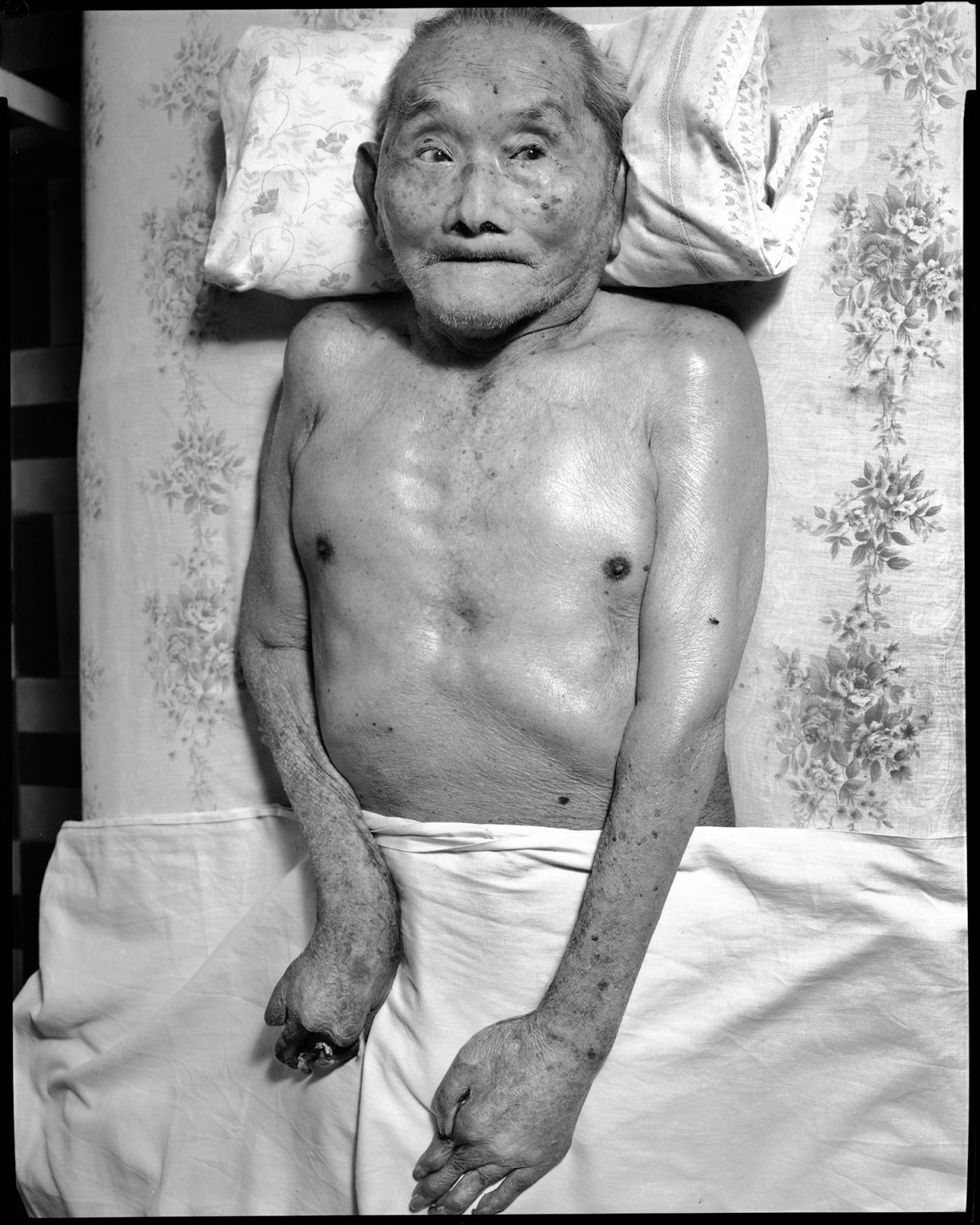

Ninety-five year old Naoe Sonoda (p. 90, 91) was silent ; he could not say anything to me. A resident of Recife in the state of Pernambuco, he was one of the last remaining of those who immigrated aboard the Kasato-Maru. He did not even blink when my huge 8 x 10 inch Deardorff camera was fixed directly over his bed. Though aware that I was being rude, I impudently pressed down on the shutter.

I was taking a commemorative photograph of him with the dream picture in the background.

Then once I finally finished shooting, he asked how much he should pay for the photographs. A barber in downtown Lima,

Tsuda was once an extremely popular figure, nicknamed"Chaplin.” However at the time I met him, due to the infirmities of old age, he was no longer capable of using a razor, an important tool of his trade. Yet even though he was not getting any patrons lately, he was still donning his white uniform every day.

The main street of the town of Guayaramerin overflows with gambling houses. The three themes of "drinking,” “striking for luck" and "buying" seem to have a devilish appeal. This intensely hot region near the source of the Amazon also appears to serve as a heroin smuggling route.

The living room of a typical “issei” household I visited in Sao Paulo had a slight air of confrontation as shouts of “Viva, Viva, Braziliero” were emitted. The great-grandparents in their eighties were gloomy and silent. A “nisei” in his sixties emitted a series of “Viva" shouts as he drew his "yonsei” grandchild onto his knees. This man's eldest son, a "sansei” in his thirties, who could not speak Japanese, grinned awkwardly, avoiding my eyes. This trifling scene took place when the national volleyball team of Japan went on a playing tour of Brazil in the middle of March, 1984. Since all the matches ended disastrously for the Japanese team with a set count of zero, the “issei” members of the family apparently had confused, mixed feelings at the time.

The Yuba Farm's ideal is to have agriculture and farming function like two wheels of a cart. Almost all the people on the communal farm participate in its ballet performances which have gained fame throughout Brazil.

The countless number of graves bearing Japanese names lined up on a gentle hill were serenely bathed in the early autumn dusk. (p. 80)

I have a feeling that I have just finished relating about half of my role through this recording of the words of nostalgia for Japan coming from the people who left a particularly strong impression on me during my three calendar years gathering stories in South America. I also carried out surveys and assignments in Hawaii and the North American continent during these past three years. In any case, this work would not have succeeded without the immense help of Toshinori Ebina, President of Office Two One, Ltd., who lent me an ear from the very planning stage. Moreover, in closing, I would like to express my thanks to the staff members of Office Two One who accompanied me on part of my journey in South America in order to do some filming for a television documentary project.

I read up avidly on the history of Japanese immigration from around the fall of 1983 to the end of February, 1984. After gathering as many materials and doing as much preliminary research as possible on the Japanese in South America, North America, and Hawaii, I decided to focus on the people still living who had boarded the Kasato-Maru, the first immigration boat to Brazil.

Then in March, 1984, I visited São Paulo for a month, where I immediately carried out a survey locally, and managed to meet with the final eight survivors. In São Paulo I ran into some strange happenings, such as finding out that 95 year old Naoe Sonoda from Kagoshima Prefecture, who was reported to be dead at that point, was actually alive. On the other hand, 93 year old Ushi Ishibaru, originally from Okinawa, died on the very day I was scheduled to interview her.

The survey undertaken locally struck with a force that would be impossible in a report based on materials collected on a desk. By meeting with the eight living witnesses, I managed to conjure up a clear image of the Kasato-Maru, which had not been much more than a phantom in my mind before I left Tokyo.

This preliminary survey, furthermore, helped me form a hazy image of the feelings of the Japanese who had permanently distanced themselves faraway from their homeland. Then finally in July of the same year I went to Brazil once more, this time all prepared to work in earnest. In any case, I ended up spending the rest of 1984 searching out the earliest immigrants to various parts of South America for this photo reportage. I feel that, as a result,

I have been able to grasp in my own way the tide of the earliest Japanese immigration to South American countries. I also realized that I should probably polish and perfect my art by gazing at things from a spot of tranquility with a quiet point of view. I hope to be able to work with "seeing” by taking a re-look at my own self via a natural body, while I express my relationship with the subject openly.

“It must have been in the 41st year of Meiji (1908) when I was 17 years old. I had responded to a recruitment notice made by the Meiji Settlement Joint Stock Company because it seemed better than going into the military service, you see. When I boarded the boat alone from Kagoshima, I had been intending to go overseas for just two or three years to make money. So I only went through the motions with the farewell cups of water.

I arrived via Kobe at the Yokohama Immigration Center. The eye doctor there gave me a really strict examination, and I was also given a talk by settlement company on what I should know about the immigration ship and the settlement area, and so on. Three days later I headed for Peru on the French ship, Caravelas. They gave me 120 yen for my boat fare. I put the 20 yen I saved from that into my waist band.

We entered the port of Callao 45 days later in the month of November. By the time I reached the Cikitoi settlement for which I was contracted, I had been cheated by Japanese gamblers, and struck by a degenerate sailor-turned thief ; so that I lost all my money.

At the plantation I was sent to, I was treated like virtually no more than a slave, and again cheated out of my wages. Then a fever started going around, and after a half of year I finally escaped from the plantation narrowly with just my life, and went on to Lima.

I managed to subsist for a year as a waiter, meanwhile picking up the language. During that time I managed to save up something toward travelling expenses, and crossed the Andes on foot. I also worked as a waiter for about a half of a year in the vicinity of Cusco.

Since it would be impossible to return to Japan draped in silver brocades by working as a waiter, I got a job with Inca Rubber, and went into the rubber mountain of Tambopata.

I saved up an adequate amount after working there over a year, so I moved down the Tambopata River to Puerto Maldonado, where there about 50 Japanese residents. And there was even one Japanese woman. That made me both happy and strangely nostalgic.

Afterwards I got wind of a most appealing job offer. So several of us young men gathered to put together a raft with driftwood. We floated along the Madre de Dios River for over 20 days before arriving in Riberalta.”

This precious living record of Japanese immigration to South America was related to me by 96 year old Bunkichi Kamikubo (p. 124), who presently resides in Florencia Varella, a suburb of Buenos Aires. His amazing memory recalls the professional story tellers of the past, and he certainly did not sound like someone over 90.

Riberalta lies in the northern extreme of Bolivia close to the Brazilian border near the source of the Amazon. This region is well known within the history of Japanese immigration for the many incidents involving rubber which broke out around the 40th year of the Meiji Period (1907). To borrow a term from Kazuo Ito's Overseas Japanese, this became the terminal station for the "wandering immigrants” from Peru. Mr. Kamikubo continued to explain recall :

"It was an extraordinarily long journey. I thought I would die. Riberalta was bustling with a good market for rubber at the time our raft drifted ashore.

There I slept with a red-haired Bolivian woman for the first time, Then I worked furiously for two years, and managed to send 2000 ven back to Japan. My folks in Kagoshima apparently built a house with that money.

After five years in Riberalta, I moved down the Amazon into Brazil. I arrived in Belém via Manaus in 1927. From there I moved on once more via São Paulo to Argentina. I'm finally settled now, and I'm satisfied where I am. A person doesn't really get fixed in a place until the birth of a grandchild.”

To the very end, Mr. Kamikubo never spoke about his homeland.

"Huh, you want to hear about Japanese bloodlines? About Japanese blood, huh?

Well the idea of having blue-eyed grandchildren has become a reality for us, you see.

A ravine forms a stream, which, in turn, becomes a river. And ultimately even the greatest river – even the Amazon — will turn into the sea. So, you see, Japanese blood runs into a great ocean here!"

This is an excerpt from a conversation I had with 75 year old Katsuo Uchiyama (p. 158), currently the managing editor of a São Paulo newspaper company. In 1930, Uchiyama went to Brazil as an immigrant farmer sharing a room on the same boat with the late author Tatsuzo Ishikawa.

“Life was rough in Fukushima. I worked spinning thread. When we landed in Santos, a bureaucrat took away my precious silk cocoons.

Is silk thread still spun in Fukushima nowadays? The morning dew on the mulberry leaves must be swished away first.”

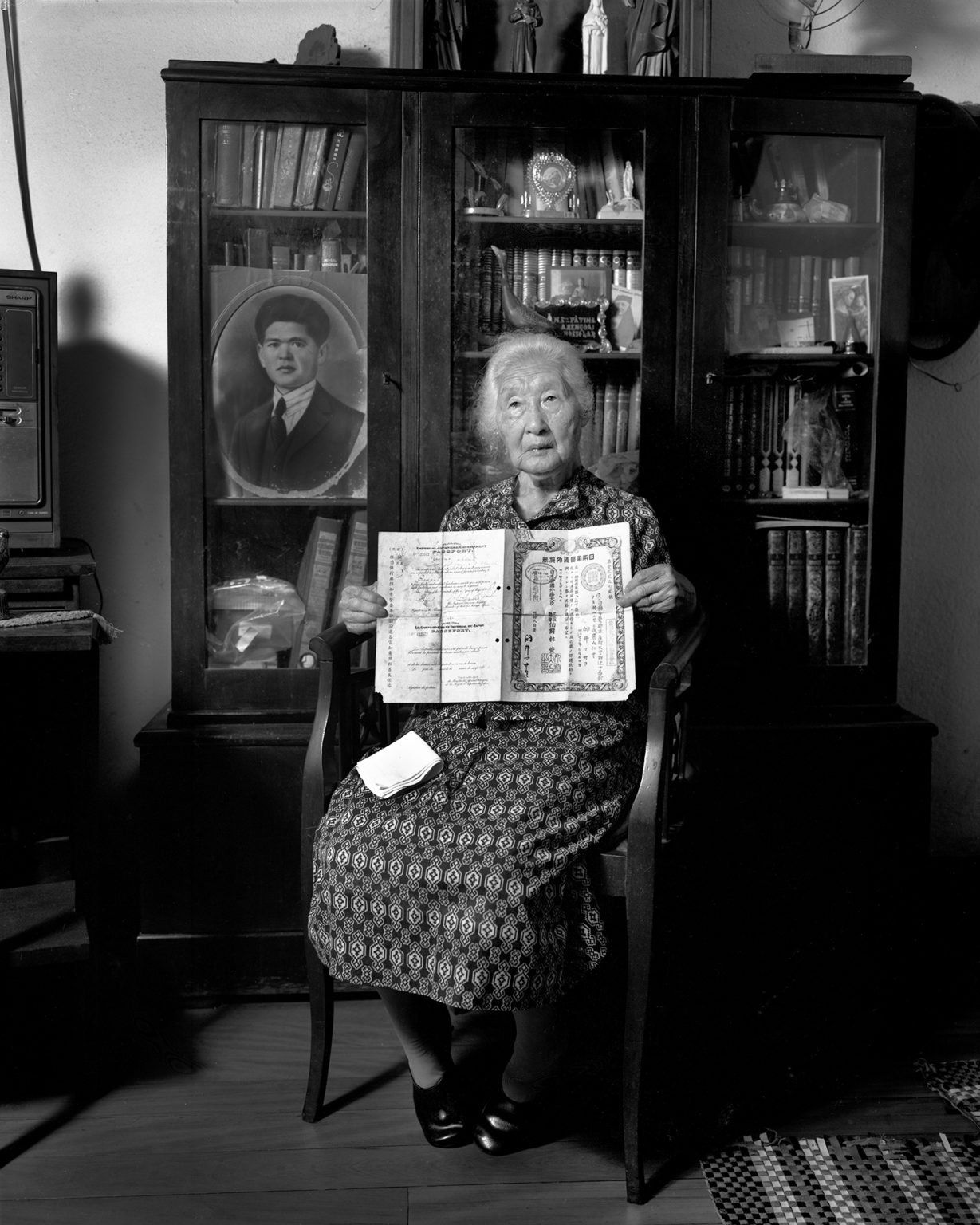

Umeno Tadano (p. 89) spoke to me in a gentle Fukushima dialect. She had not returned to her native country in the 76 years since she moved to Brazil. I met her in Iguape in the state of São Paulo. Just two days after I got her story and photographs, she died peacefully, as if in a deep sleep. She was 101 years old.

“We were very happy. Truly happy. However life became a bit rough for both of us after our legs and hips started acting up.”

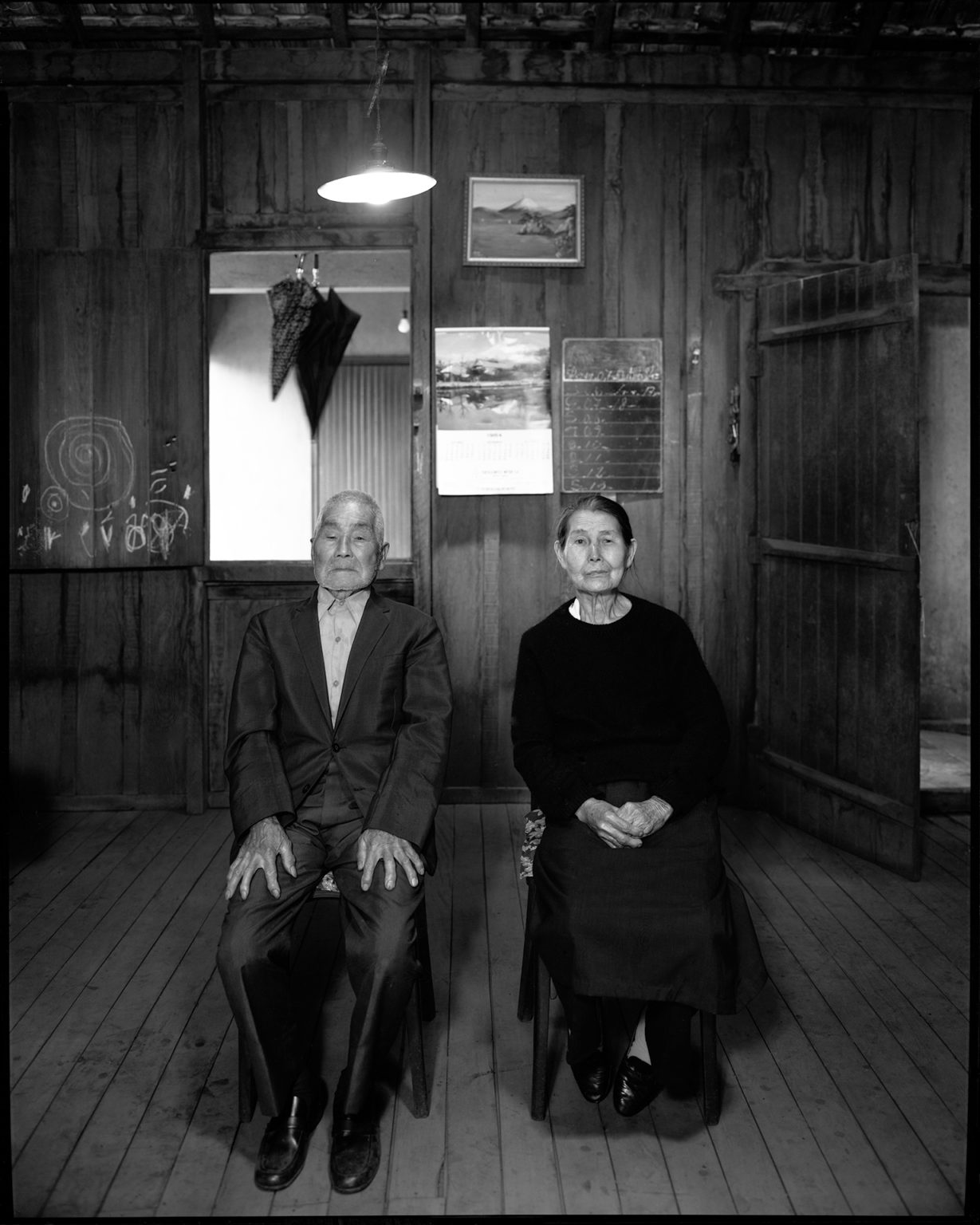

This comment came from 84 year old Kan-ichi Takeshita (p. 94), a man who immigrated to South America on his own accord, and is said to be the first of the “issei” (first generation) to marry a non-Japanese. Takeshita and his physically weak wife led a quiet life together in São Paulo, translating the dialogue of Shochiku movies like the “Tora-san” series into Portuguese.

"One out of every three 'nisei' (second generation) and 'sansei' (third generation) children in Lima were assisted out of the womb by me. In the old days giving birth was the roughest work of all for ‘issei'

women. Birth and death occasionally came together. The 'sansei' and 'yonsei' (fourth generation) are very lucky because nowadays proper hospitals exist here in Peru.” This is what I heard from 87 year old Chidori Kuroiwa (p. 96, 97), an expert midwife now living in the Casilla section of Lima. There are said to be just under 80,000 people of Japanese descent in Peru, and Ms. Kuroiwa helped deliver some 4,700 of them.

Spring keeps coming, Itsu mademo

But I don't return. Kaeranu Haru ka

Chilled to the bone, Hitoyo sao

I stand in the rain Otsuru Amadare

Which falls all night. Mi no naka ni hiyu

Shigeichi

This is a posthumous poem by Shigeichi Sakai (p.92), the lyricist of “Hietsuki-bushi," a folk song from Miyazaki Prefecture. My reportage diary indicates that I visited Mr. Sakai's house in Suzano in the state of Sao Paulo on March 31, 1984, and received photos from him. I thereafter returned to Japan for one month. When I went back to Brazil again on July 12th, it was already too late to meet him any more, for he had just passed away at age 83.

“Aramasa-san, where you're standing now, as well as this road, that church over there and this hill ? in fact, as far as you could see consisted of a great primeval forest. Attracted long ago to the magical power of the words ‘pioneer spiri?, I settled in the hinterlands. And then I spent 50 years making that into this lovely farm.

But the 'sansei' and 'yonsei' leave even this dear settlement to go off to the cities to find a job; and then they become fancy clerks and the like. So is this why we of the first generation worked so hard to put our descendents into college ?”

The above is an excerpt from a conversation I had with 84 year old Zenji Watanabe (p. 29, 66), a pioneer Japanese settler living in Colonia Esperanca in the state of Parana.

“I was tricked into going through with a marriage by photograph. And then tricked and put on a boat to Buenos Aires. Then I was deceived and sent up here via the La Plata estuary. The men in my life drank a lot. If I happened to sleep with someone else after an argument, then that would be the end of everything. A woman gets deceived throughout her life. Before I realized it, I was left in La Colmena all by myself. The men who deceived me were long gone."

This was related to me in a pleasant tone by 86 year old Masuno Kanazawa (p. 136) in La Colmena, Paraguay. Power transmission lines had been opened up in recent years in La Colmena, so refrigerators and the like are now in use in the city. Therefore, it is no longer a problem to make ice pillows for people who have suddenly taken ill. The highway to the capital has also been paved, so that “Colmena Fuji” can now be reached within three hours from Asuncion. Vigorous activity was being carried out by the local Agricultural Collective in the fifteenth year since its founding.

Masuno's homemade red miso (soy bean) paste with a tantalizingly sharp malt fragrance and her unrefined soy grains (moromi) were simply out of this world. It may seem a bit ironic that I received some to take back to Japan as a souvenir.

“The only Japanese who is not a laundryman" is the catch phrase by which a leading Buenos Aires journal designated 87 year old Tsutomu Matsunaga (p. 130) when he retired as the manager of the local La Plata Jockey Club. People of Japanese descent somehow took over the laundry profession in Argentina, and sort of became the sole agent in the introduction of modern equipment.

"Until the very end my mother greatly looked forward to your visit. You didn't show up for more than six months after the Japanese Society of Buenos Aires first telephoned to say you would be coming for an interview.”

This is what 75 year old Nario Komaki told to me about his mother Karu, who had just died on June 2, 1984, at age 94. Karu had originally immigrated to Brazil on Kasato-Maru before moving on to Argentina. I took a commemorative photograph of Nario (p. 125) in front of his mother's grave in Tucuman, about 1,200 kilometers to the north of Buenos Aires.

“This is a picture of a cavalry buggler, which is what I wanted to be when I grew up during my boyhood. Here is a picture of the daredevil warrior Genta Yoshihira at age 19 on his favorite horse during the Heiji Disturbance (1160). Last, but not least is a portrait of my dear departed wife.” Explained 96 year old amateur painter Kameki Obara (p. 40, 41). His face was slightly flushed as he gladly pointed to the framed pictures on the wall in his house. He was one of the earliest Japanese residents of Santos, in the state of Sao Paulo.

“I naturally had dreams of making a fortune!

I really waited a long time to receive a passport from the country. The boat fare was expensive, so I sneaked on. Yes, I was a stowaway. In those days there were occasionally stowaways like myself. I worked on the boat, and then ran away at a port which took my fancy. When I ventured from Valparaiso, Chile to Peru, I had absolutely no trouble even without a proper visa since the Bolivian border guard was so loose. I have a true Yamato (native Japanese) spirit !” said 86 year old Sadao Matsumoto (p. 121) when I took his photograph in Valle de la Luna in the suburbs of La Paz, Bolivia.

“A very human dilemna going beyond questions of good and evil laid in the fate of the Japanese immigrants, who were not only forced out of their homeland during the collapse of the feudal society and the subsequent establishment of the modern capitalism developed to replace it ; for they also had to work toward the modernization of the nation where they settled next. This dilemna has been described succinctly as the 'assimilation process'.......

Human beings should not live amidst contradictions and complications forever. Furthermore, even when they are feeling homesick, immigrants can not exactly ignore the real life they have. An immigrant will start feeling comfortable once he comes to have affection and a sense of responsibility toward the land where he is actually residing.

The descendants of the first immigrants are now growing up as Brazilians. They go against the wishes of their ‘issei' parents and guardians to marry the natives, and/or to participate as local people in student and various other political movements.”

The aforementioned excerpt was quoted from the voluminous History of Immigrant Life with the permission of its author, Tomoo Handa (p. 99), a 79 year old painter who lives in Sao Paulo.

"I hate to say this to someone who has travelled so far to visit me. But I don't want to meet the eyes of a photographer. I have no desire to expose my ugly decrepit appearance,” said 86 year old Ise Hayashi, a haiku poet living in Sao Paulo. Twice on the telephone at the beginning of April, 1984, she refused my request for an interview ; in fact, she was the only person from whom I could not get a photograph during this assignment.

I must say that I was rather amazed to hear modest-sounding expressions like “exposing my decrepitness” in Brazil when they are in the process of dying out in Japan these days. Ise Hayashi is the younger sister of the late great novelist Jun-ichiro Tanizaki. Born in Kakigara-cho, Nihombashi, the heart of traditional Tokyo, she spoke with a pure, crisp Edo accent that still remains in my ears.

Just one grave Shogai o

I've secretly paid respects to Kakure mairi no

All my life. Haka hitotsu

Ise

Eiji Fukumoto (p.104,105) of Puerto Maldonado, Peru told me, “I spent 20 years building the park at Centro Plaza all by myself. The palm trees growing there are rare in these parts, and they don't exist all in Kagoshima. I'm the only true ‘issei’ of Japanese descent here in Puerto Maldonado.”

Ninety-two year old Fukumoto, also known as Donpanchito, was one of the earliest immigrants to Riberalta along the Beni River in Bolivia. However he was unable to forget Puerto Maldonado, and is now the only one left of the immigrants who moved back there. “Donpanchito” is an honorary title given to him by the local residents.

“I never had my shoulder pleasantly hugged by him even once up to now," 90 year old Katsuyo Hiromori (p. 47) suddenly confessed to me in a whisper as I was taking her picture in her home in Maringa in the state of Parana.

Yoshimitsu Nakamura (p. 146), the 72 year old Chairman of the Japanese Society of Bauru in the state of Sao Paulo, made the brief comment, “I only finally reached the decision to be buried here in Brazil when I held my blue-eyed grandchildren for the first time.”

Ninety-five year old Naoe Sonoda (p. 90, 91) was silent ; he could not say anything to me. A resident of Recife in the state of Pernambuco, he was one of the last remaining of those who immigrated aboard the Kasato-Maru. He did not even blink when my huge 8 x 10 inch Deardorff camera was fixed directly over his bed. Though aware that I was being rude, I impudently pressed down on the shutter.

“There are pines, bamboo, and plum trees, as well as wild cherry trees. An arched bridge lies in the center, and Mount Fuji can be seen in the distance,” said 91 year old Ichiro Hironaka (p. 100) of Lima to describe the painting on his living room wall which apparently depicted a dream of his.

I was taking a commemorative photograph of him with the dream picture in the background.

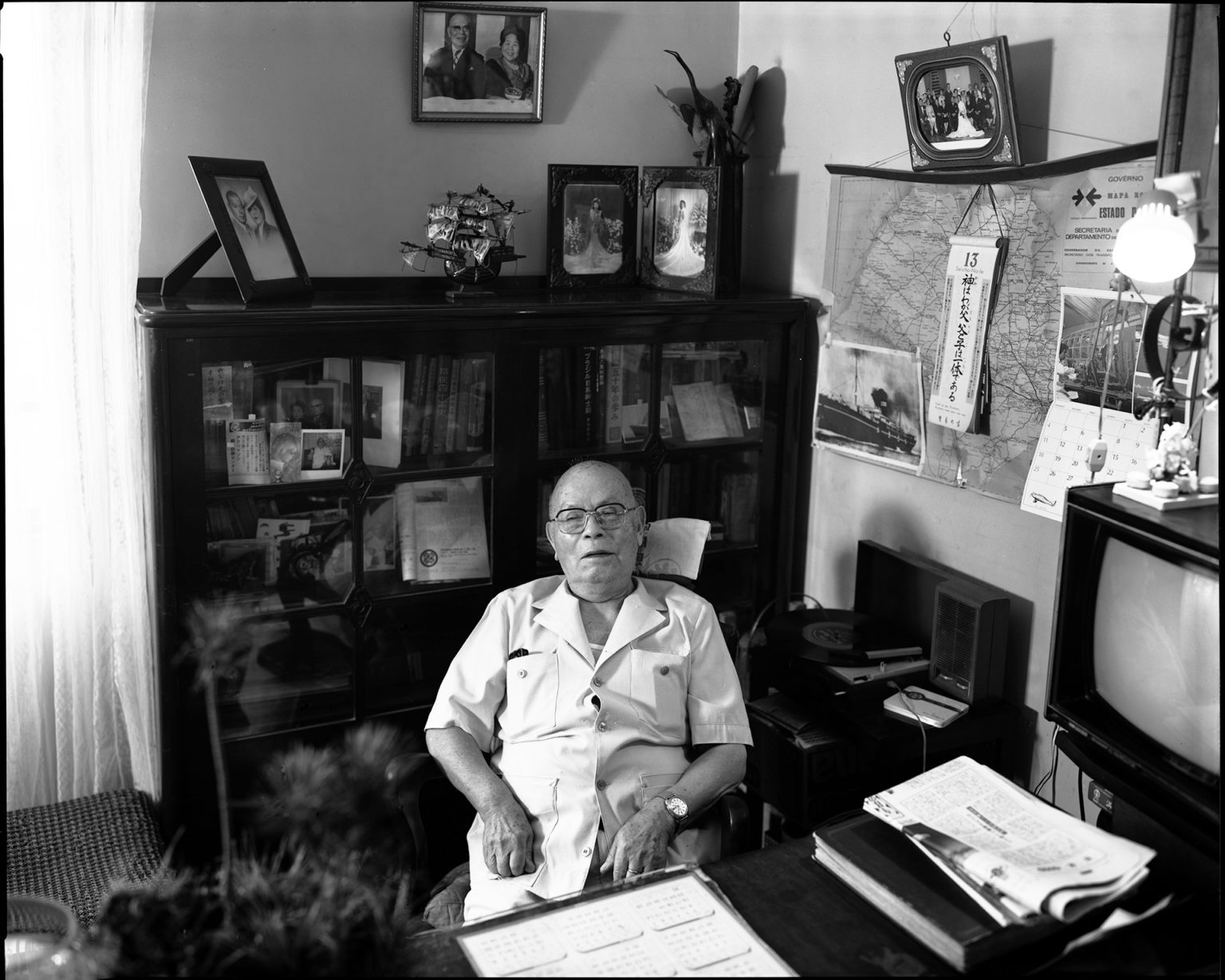

“I don't need a photo. Let's just talk. I really don't need a photo,” said eighty-nine year old Johei Isuda (p. 112).

Then once I finally finished shooting, he asked how much he should pay for the photographs. A barber in downtown Lima,

Tsuda was once an extremely popular figure, nicknamed"Chaplin.” However at the time I met him, due to the infirmities of old age, he was no longer capable of using a razor, an important tool of his trade. Yet even though he was not getting any patrons lately, he was still donning his white uniform every day.

“Chinese people would stick to all the money they had. And when the odds were just about nil, they would simply go home. We Japanese are different. We kept on waiting for a better turn in the tide, while getting stripped of everything,” remarked 88 year old Shigeo Kanda (p. 119), the only Japanese “issei” in Guayaramerin, which takes one day and night by waterway from Riberalta, the terminus for the over one thousand (estimated) Japanese who flowed in from Peru.

The main street of the town of Guayaramerin overflows with gambling houses. The three themes of "drinking,” “striking for luck" and "buying" seem to have a devilish appeal. This intensely hot region near the source of the Amazon also appears to serve as a heroin smuggling route.

"In 1935, I launched my Kabuki career playing Ishido Maru, and took my final curtain call in 1968 as Nezumi Kozo, the "Mouse Accolyte," commented Mitsuishi Takeno (p. 148). An 87 year old resident of Bastos in the Sao Paulo state, he also goes by the stage name of Kikusho Onoe. The supervisor of the Hakuko Drama Troupe, Onoe had been extolled by the “issei” immigrant community as a master of rapid transformation. At the time I met with him, he was quietly living out his post-retirement years in the spot which had been as the headquarters for his theatrical troupe for over four decades.

“I came to Brazil as an immigrant farmer, but now I'm the top fisherman in this country. After undergoing extremes, a person can do anything. During the war, I was put into an internment camp in California. But I managed to get by because I have all this strength,” stated Toshimatsu Ono (p. 152) with a smile as he drew his "nisei” wife over to him by her shoulders. Eighty-four year old Ono owns around 15 or so tuna boats and the like. He is the “don” of the port of Santos.

The living room of a typical “issei” household I visited in Sao Paulo had a slight air of confrontation as shouts of “Viva, Viva, Braziliero” were emitted. The great-grandparents in their eighties were gloomy and silent. A “nisei” in his sixties emitted a series of “Viva" shouts as he drew his "yonsei” grandchild onto his knees. This man's eldest son, a "sansei” in his thirties, who could not speak Japanese, grinned awkwardly, avoiding my eyes. This trifling scene took place when the national volleyball team of Japan went on a playing tour of Brazil in the middle of March, 1984. Since all the matches ended disastrously for the Japanese team with a set count of zero, the “issei” members of the family apparently had confused, mixed feelings at the time.

“Let's make a silent prayer,” reverberated the low yet severe voice of 76 year old Kinsuke Minowa (p. 36, 145) in the common dining room. Then a chorus of about 40 or 50 voices shouted in unison, “Let us partake now.” The people live and work communally on the Yuba Farm in 3 Allianca in the Sao Paulo state.

The Yuba Farm's ideal is to have agriculture and farming function like two wheels of a cart. Almost all the people on the communal farm participate in its ballet performances which have gained fame throughout Brazil.

“Here rest the souls of the Japanese ‘issei' who dedicated themselves to the Brazilian nation. People of Japanese descent played an especially key role in the settling of this region. However times have changed, and so has farming. Thus, the onetime residents of this area have dispersed all over Brazil. But many of the people I miss return here once a year for O-bon (the festival of the dead),” explained 90 year old Ryoichi Kodama (p. 34). He was decked out in a “happi" coat for “bon” dancing when we spoke at the plaza in Alvares Machado, Sao Paulo, where an abandoned Japanese school lies.

The countless number of graves bearing Japanese names lined up on a gentle hill were serenely bathed in the early autumn dusk. (p. 80)

I have a feeling that I have just finished relating about half of my role through this recording of the words of nostalgia for Japan coming from the people who left a particularly strong impression on me during my three calendar years gathering stories in South America. I also carried out surveys and assignments in Hawaii and the North American continent during these past three years. In any case, this work would not have succeeded without the immense help of Toshinori Ebina, President of Office Two One, Ltd., who lent me an ear from the very planning stage. Moreover, in closing, I would like to express my thanks to the staff members of Office Two One who accompanied me on part of my journey in South America in order to do some filming for a television documentary project.

English Translation / Lora Sharnoff

南米移民一世たちの取材によせて / 新正 卓

1980年の秋、旧満州で離別した私の肉親が35年ぶりに一時帰国をするという事件が降って湧いた。

位牌に戒名まで刻まれていたこの残留婦人の帰国は、わが一族郎党の驚愕と喜びを極端に揺り動かした。私はこの事件を目の当たりにしたことを契機に、祖国日本を永く遠く離れている日本人の心情に深くかかわりたい、深くかかわることが、今、自分にとってもっとも重要な仕事になるのではないだろうか、こんな予感をもつことになった。

日本に生を受け、この島国に育ったというだけで私は日本人です、あるいは私の祖国は日本なのです、ということに果たしてなるのだろうか。それはたんに国籍を所持しているというだけの、まったく根拠の希薄なことなのではないだろうか。先人達が育んだ日本固有の文化をしっかりと受け継いでこそ真の意味での国際人といえるのではないだろうか。こんな平易な、あたりまえのことを、私がつね日頃生業としている広告制作のための撮影の合間に、たびたび考えるようになりはじめていた。

位牌に戒名まで刻まれていたこの残留婦人の帰国は、わが一族郎党の驚愕と喜びを極端に揺り動かした。私はこの事件を目の当たりにしたことを契機に、祖国日本を永く遠く離れている日本人の心情に深くかかわりたい、深くかかわることが、今、自分にとってもっとも重要な仕事になるのではないだろうか、こんな予感をもつことになった。

日本に生を受け、この島国に育ったというだけで私は日本人です、あるいは私の祖国は日本なのです、ということに果たしてなるのだろうか。それはたんに国籍を所持しているというだけの、まったく根拠の希薄なことなのではないだろうか。先人達が育んだ日本固有の文化をしっかりと受け継いでこそ真の意味での国際人といえるのではないだろうか。こんな平易な、あたりまえのことを、私がつね日頃生業としている広告制作のための撮影の合間に、たびたび考えるようになりはじめていた。

遠く日本を、明治の昔に飛翔した初期移住者たちの追跡調査を自分の手でできないものだろうか。このテーマの実行こそ、日本人という存在が少々気になりだした私を触発してくれるはずだし、日本を外側から見詰め直す格好の題材であるはずだと密かに決心した。

1983年の秋頃から、翌84年の2月末までに日本人の移住史を読みあさり、南米、北米、ハワイ州の資料の収集と下調べを可能なだけすませて、標的をブラジルの第1回移民船の笠戸丸の現存者にしぼりこんだ。そして、84年の3月からひと月の予定でサンパウロに飛び、ただちに現地調査を開始して、8名の最後の現存者にお会いすることができたわけである。この時点で、死亡説にかたむいていた鹿児島出身の園田猶衛さん(95歳)の存命確認とか、インタビューの予定日に他界されてしまった沖縄出身の石原ウシさん(死亡当時93歳)のような事件に遭遇したり、現地での生きた取材調査は机上の資料調査にはない迫力でせまってきた。東京では幻に近かった笠戸丸の船影も、8名の生き証人ひとりひとりにお会いするにしたがって、イメージがはっきりと浮かび上がってきたのである。

この予備調査で“祖国を永く遠く離れている日本人の心情”に深くかかわる切り口が漠然と見えてきた。いよいよ本腰をいれて態勢を整え直し、同年の7月に再度のブラジル渡航になった。とにもかくにも昨年いっぱい、南米各国に初期の移民の方方を探し求めての撮影取材行となったのである。その結果として、取材させていただいた方々は最終的に204人に及び、日本人の南米5カ国への初期の流れが、自分なりにつかめ得たような気がする。

平易なこころと静かな視点でものを見詰めることの大切さを、自分の仕事の極意にすべきなのではないか、より自然体で自分自身を見詰め直し、対象とのかかわりを素直に表現することによって、私は“見る”ことにかかわりあうことを仕事にした人間になりきれるのではあるまいか―。

「確か、明治41年、数えで18歳でした。明治植民合資会社の告知に応募したのです。兵役に行くよりましだったからね。

たったひとり鹿児島から船に乗った時は2、3年の出稼ぎのつもりだったので、形だけの水杯でした。神戸経由で横浜の移民収容所に入って、眼医者のきつい検査や、植民会社からは移民船や入植地での心得を聞かされて、3日後フランス船のカラベラス号でペルーに移住したのです。

船賃は120円もとられてしまって、腹巻きの残金は20円を欠いていました。カヤオの港には45日目の11月に入港しました。契約先のチキトイに入植するまでに、日本人の博徒にだまされたり、船員くずれの強盗に見舞われて持ち金を全部まきあげられてしまいました。

配耕先ではまるで奴隷の代替用員そのままで、賃金もだまされ、熱病も流行って、とうとう半年日に命からがら脱耕してしまいリマ市に出ました。

1年間ボーイをして飢えをしのぎ、言葉を習いました。この間に、多少の路銀ができたので、歩いて、アンデスを越え、半年間クスコあたりでもボーイをしました。

錦衣帰国するためには、ボーイではだめで、インカ・ゴムに雇われ、タンボパタのゴム山に入ったのです。1年以上働いたので相応の蓄えができ、タンボパタ川を下り、プエルト・マルドナドに移動したのです。そこには日本人が50人程も居て、日本の女もひとりいました。とても懐かしく、嬉しかった。

その後もっとうまい仕事の話をきいたので、若い者が数人集まって、流木で筏を組んで、マドレ・デ・ディオス川を20日以上も流れて、ボリビアのリベラルタに行き着いたのです」

驚嘆に値する記憶力は、いにしえの語り部を思わせ、とても九十数歳には感じられなかった。リベラルタはボリビアの北端にあり、ブラジルとの国境近くアマゾン源流地帯に位置している。明治40年当時この地方でゴムに関する事件が多発したことは移民史に名高く、ペルーからの日系の“流れ移民”(「海外日系人」掲載、伊藤一男氏の表現を拝借しました)の終着駅であったようだ。

「途方もない長い、ながい旅だった。死ぬる旅だったよ。私達が筏で漂着したとき、リベラルタはゴム景気でにぎわっていた。

ボリビアの毛の紅い女をはじめて抱いた。それから2年間、遮二無二働いて、日本に2000円送った。鹿児島ではその金で家を建てたそうだ。

5年たって、アマゾンを下り、ブラジルに移動しました。マナウスを経て昭和2年に河口のベレンから、サンパウロを経て、アルゼンチンに再移住したのです。

いま、やっと落ち着いて、ここに満足しています。人間、孫ができてはじめて腰が落ち着くものです」

この貴重な生きた南米日系移民史は、ブエノスアイレス市郊外のフロレンシオ・バレラに住む、上久保文吉さん(96歳)からの聞き書きである。上久保さんは最後まで祖国の話を持ち出さなかった。(124ページ掲載)

「えっ、血の話?」

「ええ、日本人の血の話ですが」

「うーん、君、今われわれには碧限の孫達の存在が現実の話題となっているのだよ。谷は小川となり、川となる。そして大河は、アマゾンでさえも最後は海となる。日本人の血は、君い、大海原となるのだ!」

昭和5年、故石川達三氏と同船同室でブラジルへ農業移民をした、現サンパウロ新聞社主幹の内山勝雄さん(75歳)との会話から。(158ページ)

「ふぐすまでは、つらかった。めい日、めい日、糸をつぶい(紡い)だぁよ。サントスに上陸したどぎ、でんじにしでた繭を、お役人がとりあげてしまっただ。いまでも、ふぐすまでは、繭の糸つぶいでんのか? 桑の葉の朝露はきらねばだめだぞい」 渡伯以来76年間、祖国福島に帰国することなく、私の撮影取材後2週間目の朝、101歳で眠るように他界した笠戸丸民の只野ウメノさんは、福島訛がとてもやさしかった。サンパウロ州のイグアッペでお会いした。(89ページ)

「ふたりともとても幸せです。ほんとに幸せですよ。ただ、ふたりとも足腰が思うようにならなくなって、生きているのがつらくなりました」

自由渡航者の竹下完一さん(84歳)夫妻は邦人移民一世のなかで、国際結婚の第1号といわれている。竹下さんは、サンパウロ市で松竹系の“寅さんもの”などのポルトガル訳を多数手がけ、病弱な妻とひっそりとふたりきりの人生を送っていた。(94ページ)

「リマに住んでいる日系の二、三世の3人にひとりは私が取りあげた子供たちです。当時の一世のおなごたちは、めでたいお産の時が一番の難業でした。産湯と死に水が同時の時がたまにありました。今はペルーにも病院があるから、三世、四世たちは幸せです」

在ペルーの日系人は約8万人弱といわれている。約4700人の嬰児を取りあげたリマ市カシィヤァに暮らす黒岩チドリさん(87歳)は名人と讃えられている。(96、97ページ)

いつまでも還らぬ春か一夜さを

落つる雨だれ身の中に冷ゆ

繁一

宮崎県の“ひえつき節”の作詩者、酒井繁一さん(死亡当時83歳)の遺詠である。私の取材日誌によれば、1984年3月31日土曜日、サンパウロ州スザーノ市のお宅を訪問、お話をうかがい、写真をいただいた。ひと月のちに、いったん帰国、同年7月12日再渡伯をしたのだが、時すでに遅く、氏は還らぬひとになっていた。(92ページ)

「あらまっさん、あんたが今立っていなさるこの道も、あそこの教会も、そしてこの丘ぜんぶ見わたす限り、大原始林じゃった。

昔は開拓者魂という言葉の魔力に魅せられて、この奥地に入植したのですけれど、50年かけてこんなに綺麗な農場に仕上げてしまった。

この親愛植民地でも、三、四世は都会に出て手に職つけたり、高級な勤め人になってしまった。わしら一世はなにがなんでも子孫達を大学に入れるために頑張ったのが裏目に出おったよ」

パラナ州、コロニア・エスペランサに住む、初期開拓移民一世の渡辺善治さん(84歳)との会話の一部である。(29、66ページ)

「だまされて写真結婚をしてしまった。だまされてブエノスアイレス行きの船にのせられた。だまされてラ・プラタ川を遡り、こんな所までつれてこられた。

男衆はいいよ。飲んだくれて、喧嘩して、不貞寝すればそれっきり。女は一生だまされて、気いつけばコルメナにひとり取り残されていた。だました連れ合い、もういない」

ブラジルの隣国パラグアイ、ラ・コルメナで聞いた金沢マスノさん(86歳)の楽しそうな口調の述懐。現在のコルメナは送電線も近年開通、冷蔵庫も使用できるようになり、急な病人の氷枕にもこまらなくなった。首都圏への道路も舗装され、アスンシオンからは3時間程でコルメナ富士が仰げるようになり、農協創立15周年を迎えて活況を呈している。

マスノさんお手製の麴の香がつんと刺激する赤味噌と醤油の実(もろみ)は絶品で、皮肉にも日本への土産にいただいた。(136ページ)

“チントレーロ(洗濯屋)でない唯一の日本人”これは松永勤さん(87歳)が、ラプラタ・ジョッキークラブの支配人を引退した時に、地元ブエノスアイレス市の一流紙が翁に冠したキャッチフレーズのひとつ。アルゼンチンにおいては洗濯屋さんの地位を日系人が独占し、近代設備の導入で一手専売の様相である。(130ページ)

「あなたが訪ねてみえることを、最後の最後まで楽しみにしていたようです。ブエノスアイレスの日系人会から取材に見えると電話があってから半年以上も、あなたは来なかった。

とうとう、6月の2日に死にました」

ブラジルからの再移住の日系一世、小牧カルさん(死亡当時94)は笠戸丸移民である。二世の長男の成雄さん(75歳)は達者な日本話で私に亡き母堂のことを話してくれた。ブエノスアイレスから北へ1200キロ、トクマン市に眠るカルさんの墓前で、成雄氏を記念撮影した。1984年10月21日のことである。(125ページ)

「これはわが少年時代の憧れ、騎兵隊ラッパ手。これは平治の乱の荒武者齢十九、悪源太義平が愛馬とひと息の図。最後は、今は亡きわが愛妻が像」

ほんのりとお顔を染められた日曜画家の小原亀喜さん(96歳)は自宅の壁に飾られた奥さんの似顔絵を指差し、嬉しそうに説明してくれた。サンパウロ州リンス市の初期住人である。(40、41ページ)

「当然一攫千金を夢みたさ! 国が造るパサ・ポルテ(旅券)を待てなんだ。

船賃は高かった。密航だよ、密航。当時は俺みたいな密航者は時折いたよ。船で働き、気に入った港でポイさ。チリのバルパライソからペルーへ入る時も、ボリビアでも国境はずさんなもので、ビザなんかなくても平気の平左だった。大和魂さ!」

ボリビア、ラパス郊外の月の谷で撮影の時の松本貞雄さん(86歳)。(121ページ)

「封建制社会の崩壊と近代資本主義の成立およびその発展過程のなかで、祖国をはみだし、しかも移住先の近代化のために働くことを余儀なくされた移民の運命のなかには、善悪を超越した人間的な悩みがあった。それはひと口に、同化過程という言葉で表現される。(中略)

しかし、人間はいつまでも矛盾葛藤のなかに生きられるものではない。また、移民の郷愁がいかに強くとも、現実の生活を無視することはできない。自分のいまたっているこの大地に、愛情と責任を感じるにしたがって、心は落ち着いてくる。子孫はブラジル人として成長しつつある。一世父兄の意思とはべつに、土地の人たちと婚姻関係をむすび、土地の人間として学生運動や政治運動にもたずさわる」

サンパウロ在住の画家、半田知雄さん(79歳)の大著『移民の生活の歴史』エピローグから抜粋をおゆるし願った。(79ページ)

「遠方からのお訪ね、恐縮です。しかし写真家の方には目文字しとうござあませんの。老醜をさらしとうござあません」

1981年の4月初め、2度にわたり私の取材願いの電話をおことわりになった、サンパウロ在住の俳人、林伊勢さん(86歳)は、今回の取材活動で唯ひとり写真をいただけなかった方だった。最近の日本の風潮では、死語になりつつある“老醜をさらず”などという奥ゆかしい言葉を、ここフラジルで拝聴できようとは言じられぬことだった。林伊勢さんは、故谷崎潤一郎さんの令妹でした。日本橋は蠣殻町生まれの純粋な江戸弁は、さわやかに今でも耳に残るおもいである。

生涯をかくれ参りの墓ひとつ

伊勢

「セントロ広場の公園は、俺ひとりで20年もかけて造ったんだよ。あそこの椰子はこの辺でもめずらしくて、鹿児島にもないねえ。このプエルト・マルドナドで本物の日系一世は、俺ひとりさ」

ドンパンチートこと福花英二さん(92歳)は、ボリビア・ベニ州リベラルタの草創期の一世であったが、ペルーのプエルト・マルドナドがわすれられずに逆移住をした生存者である。ドンパンチートとは住民が彼に奉った尊称である。(104、105ページ)

「こんひとに、こげんに肩をだいてもろうたこと、いむまでにいちども有り申さん」

パラナ州マリンガ市のお宅で撮影中、ふと私に小声でもらした広森カツヨさん(90歳)。(47ページ)

「碧い日の孫を初めて抱きあげた時、このブラジルの土になる決心がやっとできました」

サンパウロ州バウルー市の日本人会長、中村好光さん(71歳)のひとこと。(146ページ)

「…………」

彼は無言。ひとことも話をしてくれない。私の大きな8✕10インチのデアドルフが彼のベッドの真上に固定された時、彼はまばたきもしなかった。私は無礼を承知していたのだが、ずうずうしくもシャッターを押した。

ペルナンブコ州レシフェ市の笠戸丸移民の現存者、園田猶衛さん(95歳)。(90、91ページ)

「松竹梅、それに山桜があって、お太鼓橋がセントロ(中央)で、遠くに富士山があります」

リマ市在住の広中一郎さん(91歳)の応接間で、氏の夢を描いた壁面をバックに記念撮影。(100ページ)

「写真はいらない。話だけしよう。写真はいらないんですよ」

結果的に撮影を完了した私に、

「写真代、いくら払えばいいんだね」

リマ市下町の住人、津田尉平さん(89歳)は、チャプリンの渾名がある人気者だったが、高齢のため商売道具のカミソリが使えなくなった。最近はひとりの客もないのだが、毎日白衣は着用している。(112ページ)

「支那人は持ち金のありったけを一点にはる。勝ち目のない時はあっさりと帰る。日本人は違う。ちびりちびりと勝機を待つ。そして身ぐるみ剥がされる」

この町グワイヤラメリンのメーンストリートには賭場があふれている。飲む、打つ、買うの三拍子が魔性の魅力となっている。酷暑のアマゾン源流地帯はヘロインの闇ルートでもあるらしい。ペルーからの邦人流れ移民(推定千数百名といわれている)の終着駅リベラルタから水路一昼夜の距離である。神田蕃男さん(88歳)はここグワイヤラメリン唯ひとりの日本人一世であった。(119ページ)

「昭和10年に“石童丸”で旗を揚げ、昭和43年に“風小僧”で幕を引かせていただきました」

伯光団を主宰して日系移民一世たちから早変わりの名人と謳われていた、尾上菊昇こと光石竹野さん(87歳)は四十数年間の劇団の本拠地サンパウロ州バストスで静かな余生を過ごしていた。(148ページ)

「農業移民で渡伯をして、今じゃ、ブラジル一の漁師だよ。人間窮すればなんでもできるよなあ。戦時、わしがカリフォルニアに収容された時、このかあちゃんがひとりで切り盛りしてたんだ」

マグロ船など十数隻を持つサントス港のドン、小野敏松さん(84歳)は、日系二世の妻の肩を引き寄せて微笑んだ。(152ページ)

「ビバ、ビバ、ブラジレイロ!!」

茶の間の空気はちょっぴりと対立ムードである。80歳代の祖父母は重苦しく無言。60歳代の二世は、ビバとブウ、ブウを連発する四世のひい孫をひざに引きよせる。日本語のできない30代の三世の長男は、私の視線をさけながらニヤリとしている。1984年3月中旬、日本ナショナル・バレーボールチームがブラジルに海外遠征をしていた時、すべての試合がセットカウント、ゼロの無惨な敗退となった。この時の一世祖父母の心境は複雑であったらしい。サンパウロ市の典型的な日系一世の家庭を訪問した時のささやかな事件である。

「黙禱。一なおれ」

低いが凜とした声が共同の食堂に響き渡る。数十人の声が「いただきます」と唱和する。箕輪勤助さん(76歳)の掛け声である。共同作業の共同生活。「農業と芸術を車の両輪のように」がここサンパウロ州、アリアンサの弓場農場の理想である。農場を構成するほとんどの人が参加をする弓場バレエ団の公演はブラジル中に知れ渡っている。(36、145ページ)

「ここはブラジルのお国にささげた日本人一世たちの魂がねむっています。この地方は特に日系が中心になって開拓をしました。しかし時代が変わり、農業も変化して、ここの住民達はプラジル全土に散らばりました。年一度のお盆の時には多数の懐かしい人々がここへ帰って来ます」

こんなことを話しながら、笠戸丸移民の児玉良一さん(90歳)は、盆踊りのハッピに腕を通していた。サンパウロ州、アルバレス・マッシャードの旧日本人学校の廃屋のある広場である。

なだらかな丘陵に沿って並ぶ無数の日本人墓地が、ひっそりと初秋の夕日を浴びていた。(34、80ページ)

足かけ3年にわたる南米取材に関するメモの中から、とくに強烈な印象を残してくれた人々の祖国恋慕の言葉を記すことによって、私の役割の半分くらいは伝え終えたような気がする。それにしてもこの3年間(もちろん、ハワイ州および北米の調査と取材も含まれているが……)企画の段階から耳を貸してくださった株式会社オフィス・トゥー・ワン社長、海老名俊則氏の絶大な援助なくしては、今回の仕事は決して成り立たなかったであろう。また、テレビドキュメントの企画としての撮影行に、南米まで一部同行してくれたオフィス・トゥー・ワンのスタッフの方々にもあわせて感謝の気持ちをあらわして筆をおきたい。

ー 1985年晩夏

1983年の秋頃から、翌84年の2月末までに日本人の移住史を読みあさり、南米、北米、ハワイ州の資料の収集と下調べを可能なだけすませて、標的をブラジルの第1回移民船の笠戸丸の現存者にしぼりこんだ。そして、84年の3月からひと月の予定でサンパウロに飛び、ただちに現地調査を開始して、8名の最後の現存者にお会いすることができたわけである。この時点で、死亡説にかたむいていた鹿児島出身の園田猶衛さん(95歳)の存命確認とか、インタビューの予定日に他界されてしまった沖縄出身の石原ウシさん(死亡当時93歳)のような事件に遭遇したり、現地での生きた取材調査は机上の資料調査にはない迫力でせまってきた。東京では幻に近かった笠戸丸の船影も、8名の生き証人ひとりひとりにお会いするにしたがって、イメージがはっきりと浮かび上がってきたのである。

この予備調査で“祖国を永く遠く離れている日本人の心情”に深くかかわる切り口が漠然と見えてきた。いよいよ本腰をいれて態勢を整え直し、同年の7月に再度のブラジル渡航になった。とにもかくにも昨年いっぱい、南米各国に初期の移民の方方を探し求めての撮影取材行となったのである。その結果として、取材させていただいた方々は最終的に204人に及び、日本人の南米5カ国への初期の流れが、自分なりにつかめ得たような気がする。

平易なこころと静かな視点でものを見詰めることの大切さを、自分の仕事の極意にすべきなのではないか、より自然体で自分自身を見詰め直し、対象とのかかわりを素直に表現することによって、私は“見る”ことにかかわりあうことを仕事にした人間になりきれるのではあるまいか―。

「確か、明治41年、数えで18歳でした。明治植民合資会社の告知に応募したのです。兵役に行くよりましだったからね。

たったひとり鹿児島から船に乗った時は2、3年の出稼ぎのつもりだったので、形だけの水杯でした。神戸経由で横浜の移民収容所に入って、眼医者のきつい検査や、植民会社からは移民船や入植地での心得を聞かされて、3日後フランス船のカラベラス号でペルーに移住したのです。

船賃は120円もとられてしまって、腹巻きの残金は20円を欠いていました。カヤオの港には45日目の11月に入港しました。契約先のチキトイに入植するまでに、日本人の博徒にだまされたり、船員くずれの強盗に見舞われて持ち金を全部まきあげられてしまいました。

配耕先ではまるで奴隷の代替用員そのままで、賃金もだまされ、熱病も流行って、とうとう半年日に命からがら脱耕してしまいリマ市に出ました。

1年間ボーイをして飢えをしのぎ、言葉を習いました。この間に、多少の路銀ができたので、歩いて、アンデスを越え、半年間クスコあたりでもボーイをしました。

錦衣帰国するためには、ボーイではだめで、インカ・ゴムに雇われ、タンボパタのゴム山に入ったのです。1年以上働いたので相応の蓄えができ、タンボパタ川を下り、プエルト・マルドナドに移動したのです。そこには日本人が50人程も居て、日本の女もひとりいました。とても懐かしく、嬉しかった。

その後もっとうまい仕事の話をきいたので、若い者が数人集まって、流木で筏を組んで、マドレ・デ・ディオス川を20日以上も流れて、ボリビアのリベラルタに行き着いたのです」

驚嘆に値する記憶力は、いにしえの語り部を思わせ、とても九十数歳には感じられなかった。リベラルタはボリビアの北端にあり、ブラジルとの国境近くアマゾン源流地帯に位置している。明治40年当時この地方でゴムに関する事件が多発したことは移民史に名高く、ペルーからの日系の“流れ移民”(「海外日系人」掲載、伊藤一男氏の表現を拝借しました)の終着駅であったようだ。

「途方もない長い、ながい旅だった。死ぬる旅だったよ。私達が筏で漂着したとき、リベラルタはゴム景気でにぎわっていた。

ボリビアの毛の紅い女をはじめて抱いた。それから2年間、遮二無二働いて、日本に2000円送った。鹿児島ではその金で家を建てたそうだ。

5年たって、アマゾンを下り、ブラジルに移動しました。マナウスを経て昭和2年に河口のベレンから、サンパウロを経て、アルゼンチンに再移住したのです。

いま、やっと落ち着いて、ここに満足しています。人間、孫ができてはじめて腰が落ち着くものです」

この貴重な生きた南米日系移民史は、ブエノスアイレス市郊外のフロレンシオ・バレラに住む、上久保文吉さん(96歳)からの聞き書きである。上久保さんは最後まで祖国の話を持ち出さなかった。(124ページ掲載)

「えっ、血の話?」

「ええ、日本人の血の話ですが」

「うーん、君、今われわれには碧限の孫達の存在が現実の話題となっているのだよ。谷は小川となり、川となる。そして大河は、アマゾンでさえも最後は海となる。日本人の血は、君い、大海原となるのだ!」

昭和5年、故石川達三氏と同船同室でブラジルへ農業移民をした、現サンパウロ新聞社主幹の内山勝雄さん(75歳)との会話から。(158ページ)

「ふぐすまでは、つらかった。めい日、めい日、糸をつぶい(紡い)だぁよ。サントスに上陸したどぎ、でんじにしでた繭を、お役人がとりあげてしまっただ。いまでも、ふぐすまでは、繭の糸つぶいでんのか? 桑の葉の朝露はきらねばだめだぞい」 渡伯以来76年間、祖国福島に帰国することなく、私の撮影取材後2週間目の朝、101歳で眠るように他界した笠戸丸民の只野ウメノさんは、福島訛がとてもやさしかった。サンパウロ州のイグアッペでお会いした。(89ページ)

「ふたりともとても幸せです。ほんとに幸せですよ。ただ、ふたりとも足腰が思うようにならなくなって、生きているのがつらくなりました」

自由渡航者の竹下完一さん(84歳)夫妻は邦人移民一世のなかで、国際結婚の第1号といわれている。竹下さんは、サンパウロ市で松竹系の“寅さんもの”などのポルトガル訳を多数手がけ、病弱な妻とひっそりとふたりきりの人生を送っていた。(94ページ)

「リマに住んでいる日系の二、三世の3人にひとりは私が取りあげた子供たちです。当時の一世のおなごたちは、めでたいお産の時が一番の難業でした。産湯と死に水が同時の時がたまにありました。今はペルーにも病院があるから、三世、四世たちは幸せです」

在ペルーの日系人は約8万人弱といわれている。約4700人の嬰児を取りあげたリマ市カシィヤァに暮らす黒岩チドリさん(87歳)は名人と讃えられている。(96、97ページ)

いつまでも還らぬ春か一夜さを

落つる雨だれ身の中に冷ゆ

繁一

宮崎県の“ひえつき節”の作詩者、酒井繁一さん(死亡当時83歳)の遺詠である。私の取材日誌によれば、1984年3月31日土曜日、サンパウロ州スザーノ市のお宅を訪問、お話をうかがい、写真をいただいた。ひと月のちに、いったん帰国、同年7月12日再渡伯をしたのだが、時すでに遅く、氏は還らぬひとになっていた。(92ページ)

「あらまっさん、あんたが今立っていなさるこの道も、あそこの教会も、そしてこの丘ぜんぶ見わたす限り、大原始林じゃった。

昔は開拓者魂という言葉の魔力に魅せられて、この奥地に入植したのですけれど、50年かけてこんなに綺麗な農場に仕上げてしまった。

この親愛植民地でも、三、四世は都会に出て手に職つけたり、高級な勤め人になってしまった。わしら一世はなにがなんでも子孫達を大学に入れるために頑張ったのが裏目に出おったよ」

パラナ州、コロニア・エスペランサに住む、初期開拓移民一世の渡辺善治さん(84歳)との会話の一部である。(29、66ページ)

「だまされて写真結婚をしてしまった。だまされてブエノスアイレス行きの船にのせられた。だまされてラ・プラタ川を遡り、こんな所までつれてこられた。

男衆はいいよ。飲んだくれて、喧嘩して、不貞寝すればそれっきり。女は一生だまされて、気いつけばコルメナにひとり取り残されていた。だました連れ合い、もういない」

ブラジルの隣国パラグアイ、ラ・コルメナで聞いた金沢マスノさん(86歳)の楽しそうな口調の述懐。現在のコルメナは送電線も近年開通、冷蔵庫も使用できるようになり、急な病人の氷枕にもこまらなくなった。首都圏への道路も舗装され、アスンシオンからは3時間程でコルメナ富士が仰げるようになり、農協創立15周年を迎えて活況を呈している。

マスノさんお手製の麴の香がつんと刺激する赤味噌と醤油の実(もろみ)は絶品で、皮肉にも日本への土産にいただいた。(136ページ)

“チントレーロ(洗濯屋)でない唯一の日本人”これは松永勤さん(87歳)が、ラプラタ・ジョッキークラブの支配人を引退した時に、地元ブエノスアイレス市の一流紙が翁に冠したキャッチフレーズのひとつ。アルゼンチンにおいては洗濯屋さんの地位を日系人が独占し、近代設備の導入で一手専売の様相である。(130ページ)

「あなたが訪ねてみえることを、最後の最後まで楽しみにしていたようです。ブエノスアイレスの日系人会から取材に見えると電話があってから半年以上も、あなたは来なかった。

とうとう、6月の2日に死にました」

ブラジルからの再移住の日系一世、小牧カルさん(死亡当時94)は笠戸丸移民である。二世の長男の成雄さん(75歳)は達者な日本話で私に亡き母堂のことを話してくれた。ブエノスアイレスから北へ1200キロ、トクマン市に眠るカルさんの墓前で、成雄氏を記念撮影した。1984年10月21日のことである。(125ページ)

「これはわが少年時代の憧れ、騎兵隊ラッパ手。これは平治の乱の荒武者齢十九、悪源太義平が愛馬とひと息の図。最後は、今は亡きわが愛妻が像」

ほんのりとお顔を染められた日曜画家の小原亀喜さん(96歳)は自宅の壁に飾られた奥さんの似顔絵を指差し、嬉しそうに説明してくれた。サンパウロ州リンス市の初期住人である。(40、41ページ)

「当然一攫千金を夢みたさ! 国が造るパサ・ポルテ(旅券)を待てなんだ。

船賃は高かった。密航だよ、密航。当時は俺みたいな密航者は時折いたよ。船で働き、気に入った港でポイさ。チリのバルパライソからペルーへ入る時も、ボリビアでも国境はずさんなもので、ビザなんかなくても平気の平左だった。大和魂さ!」

ボリビア、ラパス郊外の月の谷で撮影の時の松本貞雄さん(86歳)。(121ページ)

「封建制社会の崩壊と近代資本主義の成立およびその発展過程のなかで、祖国をはみだし、しかも移住先の近代化のために働くことを余儀なくされた移民の運命のなかには、善悪を超越した人間的な悩みがあった。それはひと口に、同化過程という言葉で表現される。(中略)

しかし、人間はいつまでも矛盾葛藤のなかに生きられるものではない。また、移民の郷愁がいかに強くとも、現実の生活を無視することはできない。自分のいまたっているこの大地に、愛情と責任を感じるにしたがって、心は落ち着いてくる。子孫はブラジル人として成長しつつある。一世父兄の意思とはべつに、土地の人たちと婚姻関係をむすび、土地の人間として学生運動や政治運動にもたずさわる」

サンパウロ在住の画家、半田知雄さん(79歳)の大著『移民の生活の歴史』エピローグから抜粋をおゆるし願った。(79ページ)

「遠方からのお訪ね、恐縮です。しかし写真家の方には目文字しとうござあませんの。老醜をさらしとうござあません」

1981年の4月初め、2度にわたり私の取材願いの電話をおことわりになった、サンパウロ在住の俳人、林伊勢さん(86歳)は、今回の取材活動で唯ひとり写真をいただけなかった方だった。最近の日本の風潮では、死語になりつつある“老醜をさらず”などという奥ゆかしい言葉を、ここフラジルで拝聴できようとは言じられぬことだった。林伊勢さんは、故谷崎潤一郎さんの令妹でした。日本橋は蠣殻町生まれの純粋な江戸弁は、さわやかに今でも耳に残るおもいである。

生涯をかくれ参りの墓ひとつ

伊勢

「セントロ広場の公園は、俺ひとりで20年もかけて造ったんだよ。あそこの椰子はこの辺でもめずらしくて、鹿児島にもないねえ。このプエルト・マルドナドで本物の日系一世は、俺ひとりさ」

ドンパンチートこと福花英二さん(92歳)は、ボリビア・ベニ州リベラルタの草創期の一世であったが、ペルーのプエルト・マルドナドがわすれられずに逆移住をした生存者である。ドンパンチートとは住民が彼に奉った尊称である。(104、105ページ)

「こんひとに、こげんに肩をだいてもろうたこと、いむまでにいちども有り申さん」

パラナ州マリンガ市のお宅で撮影中、ふと私に小声でもらした広森カツヨさん(90歳)。(47ページ)

「碧い日の孫を初めて抱きあげた時、このブラジルの土になる決心がやっとできました」

サンパウロ州バウルー市の日本人会長、中村好光さん(71歳)のひとこと。(146ページ)

「…………」

彼は無言。ひとことも話をしてくれない。私の大きな8✕10インチのデアドルフが彼のベッドの真上に固定された時、彼はまばたきもしなかった。私は無礼を承知していたのだが、ずうずうしくもシャッターを押した。

ペルナンブコ州レシフェ市の笠戸丸移民の現存者、園田猶衛さん(95歳)。(90、91ページ)

「松竹梅、それに山桜があって、お太鼓橋がセントロ(中央)で、遠くに富士山があります」

リマ市在住の広中一郎さん(91歳)の応接間で、氏の夢を描いた壁面をバックに記念撮影。(100ページ)

「写真はいらない。話だけしよう。写真はいらないんですよ」

結果的に撮影を完了した私に、

「写真代、いくら払えばいいんだね」

リマ市下町の住人、津田尉平さん(89歳)は、チャプリンの渾名がある人気者だったが、高齢のため商売道具のカミソリが使えなくなった。最近はひとりの客もないのだが、毎日白衣は着用している。(112ページ)

「支那人は持ち金のありったけを一点にはる。勝ち目のない時はあっさりと帰る。日本人は違う。ちびりちびりと勝機を待つ。そして身ぐるみ剥がされる」

この町グワイヤラメリンのメーンストリートには賭場があふれている。飲む、打つ、買うの三拍子が魔性の魅力となっている。酷暑のアマゾン源流地帯はヘロインの闇ルートでもあるらしい。ペルーからの邦人流れ移民(推定千数百名といわれている)の終着駅リベラルタから水路一昼夜の距離である。神田蕃男さん(88歳)はここグワイヤラメリン唯ひとりの日本人一世であった。(119ページ)

「昭和10年に“石童丸”で旗を揚げ、昭和43年に“風小僧”で幕を引かせていただきました」

伯光団を主宰して日系移民一世たちから早変わりの名人と謳われていた、尾上菊昇こと光石竹野さん(87歳)は四十数年間の劇団の本拠地サンパウロ州バストスで静かな余生を過ごしていた。(148ページ)

「農業移民で渡伯をして、今じゃ、ブラジル一の漁師だよ。人間窮すればなんでもできるよなあ。戦時、わしがカリフォルニアに収容された時、このかあちゃんがひとりで切り盛りしてたんだ」

マグロ船など十数隻を持つサントス港のドン、小野敏松さん(84歳)は、日系二世の妻の肩を引き寄せて微笑んだ。(152ページ)

「ビバ、ビバ、ブラジレイロ!!」

茶の間の空気はちょっぴりと対立ムードである。80歳代の祖父母は重苦しく無言。60歳代の二世は、ビバとブウ、ブウを連発する四世のひい孫をひざに引きよせる。日本語のできない30代の三世の長男は、私の視線をさけながらニヤリとしている。1984年3月中旬、日本ナショナル・バレーボールチームがブラジルに海外遠征をしていた時、すべての試合がセットカウント、ゼロの無惨な敗退となった。この時の一世祖父母の心境は複雑であったらしい。サンパウロ市の典型的な日系一世の家庭を訪問した時のささやかな事件である。

「黙禱。一なおれ」

低いが凜とした声が共同の食堂に響き渡る。数十人の声が「いただきます」と唱和する。箕輪勤助さん(76歳)の掛け声である。共同作業の共同生活。「農業と芸術を車の両輪のように」がここサンパウロ州、アリアンサの弓場農場の理想である。農場を構成するほとんどの人が参加をする弓場バレエ団の公演はブラジル中に知れ渡っている。(36、145ページ)

「ここはブラジルのお国にささげた日本人一世たちの魂がねむっています。この地方は特に日系が中心になって開拓をしました。しかし時代が変わり、農業も変化して、ここの住民達はプラジル全土に散らばりました。年一度のお盆の時には多数の懐かしい人々がここへ帰って来ます」

こんなことを話しながら、笠戸丸移民の児玉良一さん(90歳)は、盆踊りのハッピに腕を通していた。サンパウロ州、アルバレス・マッシャードの旧日本人学校の廃屋のある広場である。

なだらかな丘陵に沿って並ぶ無数の日本人墓地が、ひっそりと初秋の夕日を浴びていた。(34、80ページ)

足かけ3年にわたる南米取材に関するメモの中から、とくに強烈な印象を残してくれた人々の祖国恋慕の言葉を記すことによって、私の役割の半分くらいは伝え終えたような気がする。それにしてもこの3年間(もちろん、ハワイ州および北米の調査と取材も含まれているが……)企画の段階から耳を貸してくださった株式会社オフィス・トゥー・ワン社長、海老名俊則氏の絶大な援助なくしては、今回の仕事は決して成り立たなかったであろう。また、テレビドキュメントの企画としての撮影行に、南米まで一部同行してくれたオフィス・トゥー・ワンのスタッフの方々にもあわせて感謝の気持ちをあらわして筆をおきたい。

ー 1985年晩夏