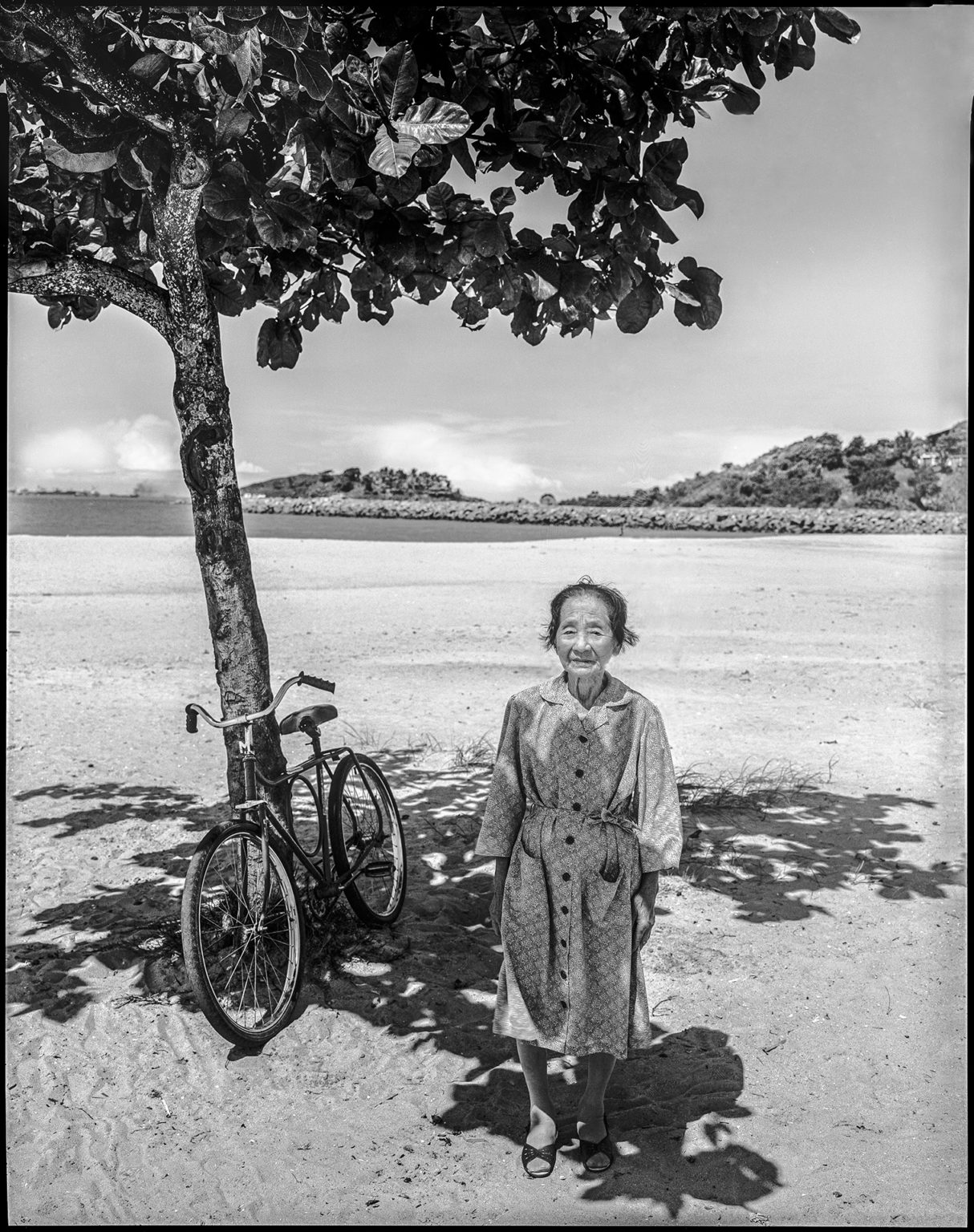

A Portrait of Japanese Immigrants

On covering First Generation Japanese Immigrants / ARAMASA Taku

In the autumn of 1980, a relative with whom my family had lost contact in the former Japanese colony of Manchuria suddenly returned to Japan temporarily for the first time in 35 years. This event stirred me very much emotionally. This relative’s name had already been carved into a Buddhist mortuary tablet, so her homecoming caused both great surprise and joy to my entire extended family. Witnessing this event also profoundly filled me with the desire to understand the feelings of Japanese who have permanently distanced themselves from their homeland. I had a hunch that attaining such comprehension might turn out to be the most important work I ever did.

I wonder if it is correct to say that I am a Japanese and that Japan is my motherland simply because I was born and brought up on this island nation. All that really means is that I possess Japanese citizenship, but it has little significance otherwise. I think of myself as an international person in the true sense precisely because I have my roots firmly planted in the unique culture of Japan which was fostered and transmitted by my ancestors. This small, ordinary matter is something I have started to think about sometimes during breaks in the commercial filming I do as my regular profession.

I wonder if it is correct to say that I am a Japanese and that Japan is my motherland simply because I was born and brought up on this island nation. All that really means is that I possess Japanese citizenship, but it has little significance otherwise. I think of myself as an international person in the true sense precisely because I have my roots firmly planted in the unique culture of Japan which was fostered and transmitted by my ancestors. This small, ordinary matter is something I have started to think about sometimes during breaks in the commercial filming I do as my regular profession.

I began to wonder if I could not make a follow-up by myself on the earliest immigrants who moved faraway from Japan in the Meiji Period (1868-1912). I privately concluded that working on this theme would detonate my gradually growing concern about the existence that is know as “Japanese," and that it would also give me the optimum chance to re-inspect the Japanese intently from an outside position.

I read up avidly on the history of Japanese immigration from around the fall of 1983 to the end of February, 1984. After gathering as many materials and doing as much preliminary research as possible on the Japanese in South America, North America, and Hawaii, I decided to focus on the people still living who had boarded the Kasato-Maru, the first immigration boat to Brazil.

Then in March, 1984, I visited São Paulo for a month, where I immediately carried out a survey locally, and managed to meet with the final eight survivors. In São Paulo I ran into some strange happenings, such as finding out that 95 year old Naoe Sonoda from Kagoshima Prefecture, who was reported to be dead at that point, was actually alive. On the other hand, 93 year old Ushi Ishibaru, originally from Okinawa, died on the very day I was scheduled to interview her.

The survey undertaken locally struck with a force that would be impossible in a report based on materials collected on a desk. By meeting with the eight living witnesses, I managed to conjure up a clear image of the Kasato-Maru, which had not been much more than a phantom in my mind before I left Tokyo.

This preliminary survey, furthermore, helped me form a hazy image of the feelings of the Japanese who had permanently distanced themselves faraway from their homeland. Then finally in July of the same year I went to Brazil once more, this time all prepared to work in earnest. In any case, I ended up spending the rest of 1984 searching out the earliest immigrants to various parts of South America for this photo reportage. I feel that, as a result,

I have been able to grasp in my own way the tide of the earliest Japanese immigration to South American countries. I also realized that I should probably polish and perfect my art by gazing at things from a spot of tranquility with a quiet point of view. I hope to be able to work with "seeing” by taking a re-look at my own self via a natural body, while I express my relationship with the subject openly.

I arrived via Kobe at the Yokohama Immigration Center. The eye doctor there gave me a really strict examination, and I was also given a talk by settlement company on what I should know about the immigration ship and the settlement area, and so on. Three days later I headed for Peru on the French ship, Caravelas. They gave me 120 yen for my boat fare. I put the 20 yen I saved from that into my waist band.

We entered the port of Callao 45 days later in the month of November. By the time I reached the Cikitoi settlement for which I was contracted, I had been cheated by Japanese gamblers, and struck by a degenerate sailor-turned thief ; so that I lost all my money.

At the plantation I was sent to, I was treated like virtually no more than a slave, and again cheated out of my wages. Then a fever started going around, and after a half of year I finally escaped from the plantation narrowly with just my life, and went on to Lima.

I managed to subsist for a year as a waiter, meanwhile picking up the language. During that time I managed to save up something toward travelling expenses, and crossed the Andes on foot. I also worked as a waiter for about a half of a year in the vicinity of Cusco.

Since it would be impossible to return to Japan draped in silver brocades by working as a waiter, I got a job with Inca Rubber, and went into the rubber mountain of Tambopata.

I saved up an adequate amount after working there over a year, so I moved down the Tambopata River to Puerto Maldonado, where there about 50 Japanese residents. And there was even one Japanese woman. That made me both happy and strangely nostalgic.

Afterwards I got wind of a most appealing job offer. So several of us young men gathered to put together a raft with driftwood. We floated along the Madre de Dios River for over 20 days before arriving in Riberalta.”

This precious living record of Japanese immigration to South America was related to me by 96 year old Bunkichi Kamikubo (p. 124), who presently resides in Florencia Varella, a suburb of Buenos Aires. His amazing memory recalls the professional story tellers of the past, and he certainly did not sound like someone over 90.

Riberalta lies in the northern extreme of Bolivia close to the Brazilian border near the source of the Amazon. This region is well known within the history of Japanese immigration for the many incidents involving rubber which broke out around the 40th year of the Meiji Period (1907). To borrow a term from Kazuo Ito's Overseas Japanese, this became the terminal station for the "wandering immigrants” from Peru. Mr. Kamikubo continued to explain recall :

There I slept with a red-haired Bolivian woman for the first time, Then I worked furiously for two years, and managed to send 2000 ven back to Japan. My folks in Kagoshima apparently built a house with that money.

After five years in Riberalta, I moved down the Amazon into Brazil. I arrived in Belém via Manaus in 1927. From there I moved on once more via São Paulo to Argentina. I'm finally settled now, and I'm satisfied where I am. A person doesn't really get fixed in a place until the birth of a grandchild.”

To the very end, Mr. Kamikubo never spoke about his homeland.

"Huh, you want to hear about Japanese bloodlines? About Japanese blood, huh?

Well the idea of having blue-eyed grandchildren has become a reality for us, you see.

A ravine forms a stream, which, in turn, becomes a river. And ultimately even the greatest river – even the Amazon — will turn into the sea. So, you see, Japanese blood runs into a great ocean here!"

This is an excerpt from a conversation I had with 75 year old Katsuo Uchiyama (p. 158), currently the managing editor of a São Paulo newspaper company. In 1930, Uchiyama went to Brazil as an immigrant farmer sharing a room on the same boat with the late author Tatsuzo Ishikawa.

Is silk thread still spun in Fukushima nowadays? The morning dew on the mulberry leaves must be swished away first.”

Umeno Tadano (p. 89) spoke to me in a gentle Fukushima dialect. She had not returned to her native country in the 76 years since she moved to Brazil. I met her in Iguape in the state of São Paulo. Just two days after I got her story and photographs, she died peacefully, as if in a deep sleep. She was 101 years old.

This comment came from 84 year old Kan-ichi Takeshita (p. 94), a man who immigrated to South America on his own accord, and is said to be the first of the “issei” (first generation) to marry a non-Japanese. Takeshita and his physically weak wife led a quiet life together in São Paulo, translating the dialogue of Shochiku movies like the “Tora-san” series into Portuguese.

women. Birth and death occasionally came together. The 'sansei' and 'yonsei' (fourth generation) are very lucky because nowadays proper hospitals exist here in Peru.” This is what I heard from 87 year old Chidori Kuroiwa (p. 96, 97), an expert midwife now living in the Casilla section of Lima. There are said to be just under 80,000 people of Japanese descent in Peru, and Ms. Kuroiwa helped deliver some 4,700 of them.

But the 'sansei' and 'yonsei' leave even this dear settlement to go off to the cities to find a job; and then they become fancy clerks and the like. So is this why we of the first generation worked so hard to put our descendents into college ?”

The above is an excerpt from a conversation I had with 84 year old Zenji Watanabe (p. 29, 66), a pioneer Japanese settler living in Colonia Esperanca in the state of Parana.

This was related to me in a pleasant tone by 86 year old Masuno Kanazawa (p. 136) in La Colmena, Paraguay. Power transmission lines had been opened up in recent years in La Colmena, so refrigerators and the like are now in use in the city. Therefore, it is no longer a problem to make ice pillows for people who have suddenly taken ill. The highway to the capital has also been paved, so that “Colmena Fuji” can now be reached within three hours from Asuncion. Vigorous activity was being carried out by the local Agricultural Collective in the fifteenth year since its founding.

Masuno's homemade red miso (soy bean) paste with a tantalizingly sharp malt fragrance and her unrefined soy grains (moromi) were simply out of this world. It may seem a bit ironic that I received some to take back to Japan as a souvenir.

This is what 75 year old Nario Komaki told to me about his mother Karu, who had just died on June 2, 1984, at age 94. Karu had originally immigrated to Brazil on Kasato-Maru before moving on to Argentina. I took a commemorative photograph of Nario (p. 125) in front of his mother's grave in Tucuman, about 1,200 kilometers to the north of Buenos Aires.

I really waited a long time to receive a passport from the country. The boat fare was expensive, so I sneaked on. Yes, I was a stowaway. In those days there were occasionally stowaways like myself. I worked on the boat, and then ran away at a port which took my fancy. When I ventured from Valparaiso, Chile to Peru, I had absolutely no trouble even without a proper visa since the Bolivian border guard was so loose. I have a true Yamato (native Japanese) spirit !” said 86 year old Sadao Matsumoto (p. 121) when I took his photograph in Valle de la Luna in the suburbs of La Paz, Bolivia.

Human beings should not live amidst contradictions and complications forever. Furthermore, even when they are feeling homesick, immigrants can not exactly ignore the real life they have. An immigrant will start feeling comfortable once he comes to have affection and a sense of responsibility toward the land where he is actually residing.

The descendants of the first immigrants are now growing up as Brazilians. They go against the wishes of their ‘issei' parents and guardians to marry the natives, and/or to participate as local people in student and various other political movements.”

The aforementioned excerpt was quoted from the voluminous History of Immigrant Life with the permission of its author, Tomoo Handa (p. 99), a 79 year old painter who lives in Sao Paulo.

I must say that I was rather amazed to hear modest-sounding expressions like “exposing my decrepitness” in Brazil when they are in the process of dying out in Japan these days. Ise Hayashi is the younger sister of the late great novelist Jun-ichiro Tanizaki. Born in Kakigara-cho, Nihombashi, the heart of traditional Tokyo, she spoke with a pure, crisp Edo accent that still remains in my ears.

Ninety-two year old Fukumoto, also known as Donpanchito, was one of the earliest immigrants to Riberalta along the Beni River in Bolivia. However he was unable to forget Puerto Maldonado, and is now the only one left of the immigrants who moved back there. “Donpanchito” is an honorary title given to him by the local residents.

Yoshimitsu Nakamura (p. 146), the 72 year old Chairman of the Japanese Society of Bauru in the state of Sao Paulo, made the brief comment, “I only finally reached the decision to be buried here in Brazil when I held my blue-eyed grandchildren for the first time.”

Ninety-five year old Naoe Sonoda (p. 90, 91) was silent ; he could not say anything to me. A resident of Recife in the state of Pernambuco, he was one of the last remaining of those who immigrated aboard the Kasato-Maru. He did not even blink when my huge 8 x 10 inch Deardorff camera was fixed directly over his bed. Though aware that I was being rude, I impudently pressed down on the shutter.

I was taking a commemorative photograph of him with the dream picture in the background.

Then once I finally finished shooting, he asked how much he should pay for the photographs. A barber in downtown Lima,

Tsuda was once an extremely popular figure, nicknamed"Chaplin.” However at the time I met him, due to the infirmities of old age, he was no longer capable of using a razor, an important tool of his trade. Yet even though he was not getting any patrons lately, he was still donning his white uniform every day.

The main street of the town of Guayaramerin overflows with gambling houses. The three themes of "drinking,” “striking for luck" and "buying" seem to have a devilish appeal. This intensely hot region near the source of the Amazon also appears to serve as a heroin smuggling route.

The living room of a typical “issei” household I visited in Sao Paulo had a slight air of confrontation as shouts of “Viva, Viva, Braziliero” were emitted. The great-grandparents in their eighties were gloomy and silent. A “nisei” in his sixties emitted a series of “Viva" shouts as he drew his "yonsei” grandchild onto his knees. This man's eldest son, a "sansei” in his thirties, who could not speak Japanese, grinned awkwardly, avoiding my eyes. This trifling scene took place when the national volleyball team of Japan went on a playing tour of Brazil in the middle of March, 1984. Since all the matches ended disastrously for the Japanese team with a set count of zero, the “issei” members of the family apparently had confused, mixed feelings at the time.

The Yuba Farm's ideal is to have agriculture and farming function like two wheels of a cart. Almost all the people on the communal farm participate in its ballet performances which have gained fame throughout Brazil.

The countless number of graves bearing Japanese names lined up on a gentle hill were serenely bathed in the early autumn dusk. (p. 80)

I have a feeling that I have just finished relating about half of my role through this recording of the words of nostalgia for Japan coming from the people who left a particularly strong impression on me during my three calendar years gathering stories in South America. I also carried out surveys and assignments in Hawaii and the North American continent during these past three years. In any case, this work would not have succeeded without the immense help of Toshinori Ebina, President of Office Two One, Ltd., who lent me an ear from the very planning stage. Moreover, in closing, I would like to express my thanks to the staff members of Office Two One who accompanied me on part of my journey in South America in order to do some filming for a television documentary project.

I read up avidly on the history of Japanese immigration from around the fall of 1983 to the end of February, 1984. After gathering as many materials and doing as much preliminary research as possible on the Japanese in South America, North America, and Hawaii, I decided to focus on the people still living who had boarded the Kasato-Maru, the first immigration boat to Brazil.

Then in March, 1984, I visited São Paulo for a month, where I immediately carried out a survey locally, and managed to meet with the final eight survivors. In São Paulo I ran into some strange happenings, such as finding out that 95 year old Naoe Sonoda from Kagoshima Prefecture, who was reported to be dead at that point, was actually alive. On the other hand, 93 year old Ushi Ishibaru, originally from Okinawa, died on the very day I was scheduled to interview her.

The survey undertaken locally struck with a force that would be impossible in a report based on materials collected on a desk. By meeting with the eight living witnesses, I managed to conjure up a clear image of the Kasato-Maru, which had not been much more than a phantom in my mind before I left Tokyo.

This preliminary survey, furthermore, helped me form a hazy image of the feelings of the Japanese who had permanently distanced themselves faraway from their homeland. Then finally in July of the same year I went to Brazil once more, this time all prepared to work in earnest. In any case, I ended up spending the rest of 1984 searching out the earliest immigrants to various parts of South America for this photo reportage. I feel that, as a result,

I have been able to grasp in my own way the tide of the earliest Japanese immigration to South American countries. I also realized that I should probably polish and perfect my art by gazing at things from a spot of tranquility with a quiet point of view. I hope to be able to work with "seeing” by taking a re-look at my own self via a natural body, while I express my relationship with the subject openly.

“It must have been in the 41st year of Meiji (1908) when I was 17 years old. I had responded to a recruitment notice made by the Meiji Settlement Joint Stock Company because it seemed better than going into the military service, you see. When I boarded the boat alone from Kagoshima, I had been intending to go overseas for just two or three years to make money. So I only went through the motions with the farewell cups of water.

I arrived via Kobe at the Yokohama Immigration Center. The eye doctor there gave me a really strict examination, and I was also given a talk by settlement company on what I should know about the immigration ship and the settlement area, and so on. Three days later I headed for Peru on the French ship, Caravelas. They gave me 120 yen for my boat fare. I put the 20 yen I saved from that into my waist band.

We entered the port of Callao 45 days later in the month of November. By the time I reached the Cikitoi settlement for which I was contracted, I had been cheated by Japanese gamblers, and struck by a degenerate sailor-turned thief ; so that I lost all my money.

At the plantation I was sent to, I was treated like virtually no more than a slave, and again cheated out of my wages. Then a fever started going around, and after a half of year I finally escaped from the plantation narrowly with just my life, and went on to Lima.

I managed to subsist for a year as a waiter, meanwhile picking up the language. During that time I managed to save up something toward travelling expenses, and crossed the Andes on foot. I also worked as a waiter for about a half of a year in the vicinity of Cusco.

Since it would be impossible to return to Japan draped in silver brocades by working as a waiter, I got a job with Inca Rubber, and went into the rubber mountain of Tambopata.

I saved up an adequate amount after working there over a year, so I moved down the Tambopata River to Puerto Maldonado, where there about 50 Japanese residents. And there was even one Japanese woman. That made me both happy and strangely nostalgic.

Afterwards I got wind of a most appealing job offer. So several of us young men gathered to put together a raft with driftwood. We floated along the Madre de Dios River for over 20 days before arriving in Riberalta.”

This precious living record of Japanese immigration to South America was related to me by 96 year old Bunkichi Kamikubo (p. 124), who presently resides in Florencia Varella, a suburb of Buenos Aires. His amazing memory recalls the professional story tellers of the past, and he certainly did not sound like someone over 90.

Riberalta lies in the northern extreme of Bolivia close to the Brazilian border near the source of the Amazon. This region is well known within the history of Japanese immigration for the many incidents involving rubber which broke out around the 40th year of the Meiji Period (1907). To borrow a term from Kazuo Ito's Overseas Japanese, this became the terminal station for the "wandering immigrants” from Peru. Mr. Kamikubo continued to explain recall :

"It was an extraordinarily long journey. I thought I would die. Riberalta was bustling with a good market for rubber at the time our raft drifted ashore.

There I slept with a red-haired Bolivian woman for the first time, Then I worked furiously for two years, and managed to send 2000 ven back to Japan. My folks in Kagoshima apparently built a house with that money.

After five years in Riberalta, I moved down the Amazon into Brazil. I arrived in Belém via Manaus in 1927. From there I moved on once more via São Paulo to Argentina. I'm finally settled now, and I'm satisfied where I am. A person doesn't really get fixed in a place until the birth of a grandchild.”

To the very end, Mr. Kamikubo never spoke about his homeland.

"Huh, you want to hear about Japanese bloodlines? About Japanese blood, huh?

Well the idea of having blue-eyed grandchildren has become a reality for us, you see.

A ravine forms a stream, which, in turn, becomes a river. And ultimately even the greatest river – even the Amazon — will turn into the sea. So, you see, Japanese blood runs into a great ocean here!"

This is an excerpt from a conversation I had with 75 year old Katsuo Uchiyama (p. 158), currently the managing editor of a São Paulo newspaper company. In 1930, Uchiyama went to Brazil as an immigrant farmer sharing a room on the same boat with the late author Tatsuzo Ishikawa.

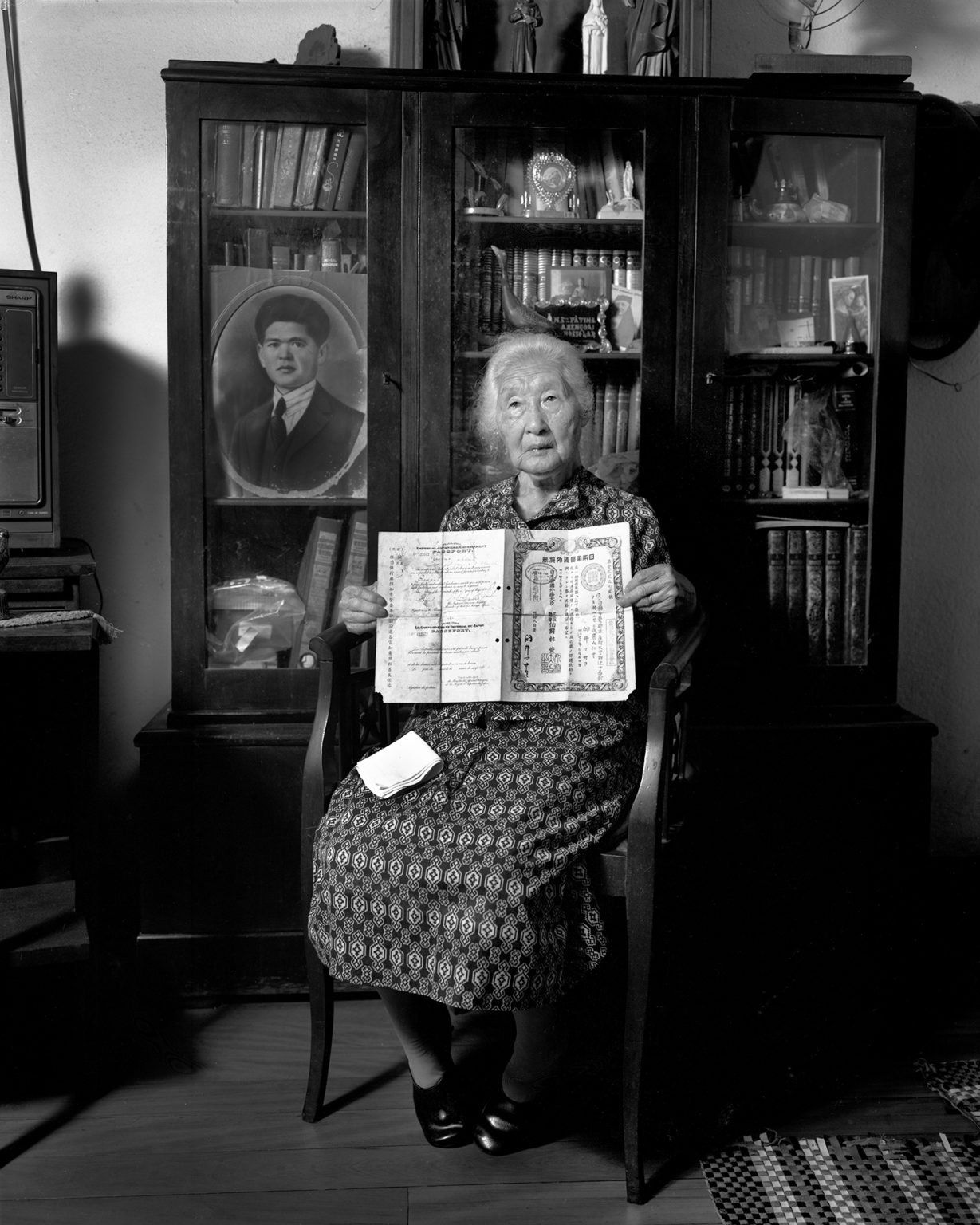

“Life was rough in Fukushima. I worked spinning thread. When we landed in Santos, a bureaucrat took away my precious silk cocoons.

Is silk thread still spun in Fukushima nowadays? The morning dew on the mulberry leaves must be swished away first.”

Umeno Tadano (p. 89) spoke to me in a gentle Fukushima dialect. She had not returned to her native country in the 76 years since she moved to Brazil. I met her in Iguape in the state of São Paulo. Just two days after I got her story and photographs, she died peacefully, as if in a deep sleep. She was 101 years old.

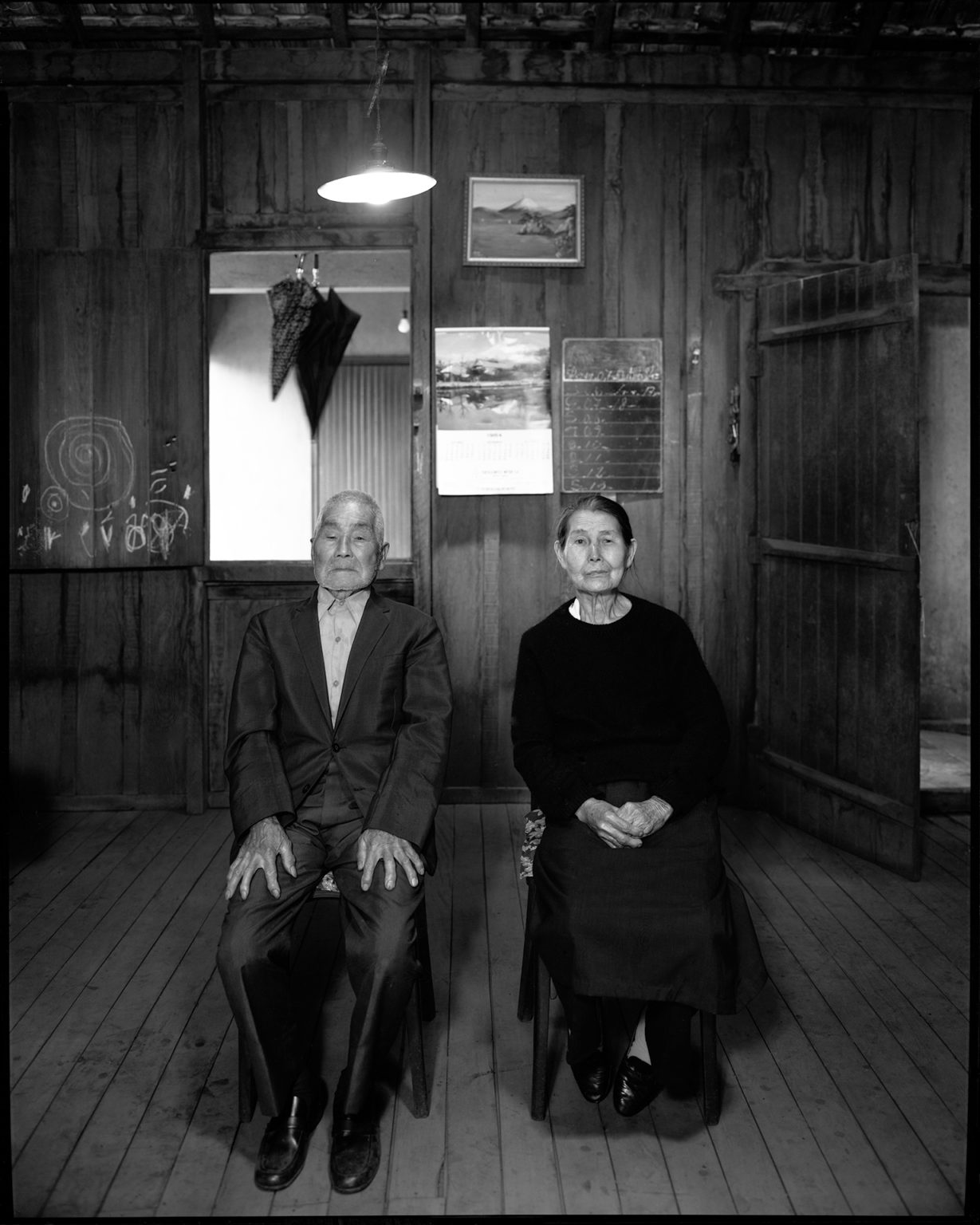

“We were very happy. Truly happy. However life became a bit rough for both of us after our legs and hips started acting up.”

This comment came from 84 year old Kan-ichi Takeshita (p. 94), a man who immigrated to South America on his own accord, and is said to be the first of the “issei” (first generation) to marry a non-Japanese. Takeshita and his physically weak wife led a quiet life together in São Paulo, translating the dialogue of Shochiku movies like the “Tora-san” series into Portuguese.

"One out of every three 'nisei' (second generation) and 'sansei' (third generation) children in Lima were assisted out of the womb by me. In the old days giving birth was the roughest work of all for ‘issei'

women. Birth and death occasionally came together. The 'sansei' and 'yonsei' (fourth generation) are very lucky because nowadays proper hospitals exist here in Peru.” This is what I heard from 87 year old Chidori Kuroiwa (p. 96, 97), an expert midwife now living in the Casilla section of Lima. There are said to be just under 80,000 people of Japanese descent in Peru, and Ms. Kuroiwa helped deliver some 4,700 of them.

Spring keeps coming, Itsu mademo

But I don't return. Kaeranu Haru ka

Chilled to the bone, Hitoyo sao

I stand in the rain Otsuru Amadare

Which falls all night. Mi no naka ni hiyu

Shigeichi

This is a posthumous poem by Shigeichi Sakai (p.92), the lyricist of “Hietsuki-bushi," a folk song from Miyazaki Prefecture. My reportage diary indicates that I visited Mr. Sakai's house in Suzano in the state of Sao Paulo on March 31, 1984, and received photos from him. I thereafter returned to Japan for one month. When I went back to Brazil again on July 12th, it was already too late to meet him any more, for he had just passed away at age 83.

“Aramasa-san, where you're standing now, as well as this road, that church over there and this hill ? in fact, as far as you could see consisted of a great primeval forest. Attracted long ago to the magical power of the words ‘pioneer spiri?, I settled in the hinterlands. And then I spent 50 years making that into this lovely farm.

But the 'sansei' and 'yonsei' leave even this dear settlement to go off to the cities to find a job; and then they become fancy clerks and the like. So is this why we of the first generation worked so hard to put our descendents into college ?”

The above is an excerpt from a conversation I had with 84 year old Zenji Watanabe (p. 29, 66), a pioneer Japanese settler living in Colonia Esperanca in the state of Parana.

“I was tricked into going through with a marriage by photograph. And then tricked and put on a boat to Buenos Aires. Then I was deceived and sent up here via the La Plata estuary. The men in my life drank a lot. If I happened to sleep with someone else after an argument, then that would be the end of everything. A woman gets deceived throughout her life. Before I realized it, I was left in La Colmena all by myself. The men who deceived me were long gone."

This was related to me in a pleasant tone by 86 year old Masuno Kanazawa (p. 136) in La Colmena, Paraguay. Power transmission lines had been opened up in recent years in La Colmena, so refrigerators and the like are now in use in the city. Therefore, it is no longer a problem to make ice pillows for people who have suddenly taken ill. The highway to the capital has also been paved, so that “Colmena Fuji” can now be reached within three hours from Asuncion. Vigorous activity was being carried out by the local Agricultural Collective in the fifteenth year since its founding.

Masuno's homemade red miso (soy bean) paste with a tantalizingly sharp malt fragrance and her unrefined soy grains (moromi) were simply out of this world. It may seem a bit ironic that I received some to take back to Japan as a souvenir.

“The only Japanese who is not a laundryman" is the catch phrase by which a leading Buenos Aires journal designated 87 year old Tsutomu Matsunaga (p. 130) when he retired as the manager of the local La Plata Jockey Club. People of Japanese descent somehow took over the laundry profession in Argentina, and sort of became the sole agent in the introduction of modern equipment.

"Until the very end my mother greatly looked forward to your visit. You didn't show up for more than six months after the Japanese Society of Buenos Aires first telephoned to say you would be coming for an interview.”

This is what 75 year old Nario Komaki told to me about his mother Karu, who had just died on June 2, 1984, at age 94. Karu had originally immigrated to Brazil on Kasato-Maru before moving on to Argentina. I took a commemorative photograph of Nario (p. 125) in front of his mother's grave in Tucuman, about 1,200 kilometers to the north of Buenos Aires.

“This is a picture of a cavalry buggler, which is what I wanted to be when I grew up during my boyhood. Here is a picture of the daredevil warrior Genta Yoshihira at age 19 on his favorite horse during the Heiji Disturbance (1160). Last, but not least is a portrait of my dear departed wife.” Explained 96 year old amateur painter Kameki Obara (p. 40, 41). His face was slightly flushed as he gladly pointed to the framed pictures on the wall in his house. He was one of the earliest Japanese residents of Santos, in the state of Sao Paulo.

“I naturally had dreams of making a fortune!

I really waited a long time to receive a passport from the country. The boat fare was expensive, so I sneaked on. Yes, I was a stowaway. In those days there were occasionally stowaways like myself. I worked on the boat, and then ran away at a port which took my fancy. When I ventured from Valparaiso, Chile to Peru, I had absolutely no trouble even without a proper visa since the Bolivian border guard was so loose. I have a true Yamato (native Japanese) spirit !” said 86 year old Sadao Matsumoto (p. 121) when I took his photograph in Valle de la Luna in the suburbs of La Paz, Bolivia.

“A very human dilemna going beyond questions of good and evil laid in the fate of the Japanese immigrants, who were not only forced out of their homeland during the collapse of the feudal society and the subsequent establishment of the modern capitalism developed to replace it ; for they also had to work toward the modernization of the nation where they settled next. This dilemna has been described succinctly as the 'assimilation process'.......

Human beings should not live amidst contradictions and complications forever. Furthermore, even when they are feeling homesick, immigrants can not exactly ignore the real life they have. An immigrant will start feeling comfortable once he comes to have affection and a sense of responsibility toward the land where he is actually residing.

The descendants of the first immigrants are now growing up as Brazilians. They go against the wishes of their ‘issei' parents and guardians to marry the natives, and/or to participate as local people in student and various other political movements.”

The aforementioned excerpt was quoted from the voluminous History of Immigrant Life with the permission of its author, Tomoo Handa (p. 99), a 79 year old painter who lives in Sao Paulo.

"I hate to say this to someone who has travelled so far to visit me. But I don't want to meet the eyes of a photographer. I have no desire to expose my ugly decrepit appearance,” said 86 year old Ise Hayashi, a haiku poet living in Sao Paulo. Twice on the telephone at the beginning of April, 1984, she refused my request for an interview ; in fact, she was the only person from whom I could not get a photograph during this assignment.

I must say that I was rather amazed to hear modest-sounding expressions like “exposing my decrepitness” in Brazil when they are in the process of dying out in Japan these days. Ise Hayashi is the younger sister of the late great novelist Jun-ichiro Tanizaki. Born in Kakigara-cho, Nihombashi, the heart of traditional Tokyo, she spoke with a pure, crisp Edo accent that still remains in my ears.

Just one grave Shogai o

I've secretly paid respects to Kakure mairi no

All my life. Haka hitotsu

Ise

Eiji Fukumoto (p.104,105) of Puerto Maldonado, Peru told me, “I spent 20 years building the park at Centro Plaza all by myself. The palm trees growing there are rare in these parts, and they don't exist all in Kagoshima. I'm the only true ‘issei’ of Japanese descent here in Puerto Maldonado.”

Ninety-two year old Fukumoto, also known as Donpanchito, was one of the earliest immigrants to Riberalta along the Beni River in Bolivia. However he was unable to forget Puerto Maldonado, and is now the only one left of the immigrants who moved back there. “Donpanchito” is an honorary title given to him by the local residents.

“I never had my shoulder pleasantly hugged by him even once up to now," 90 year old Katsuyo Hiromori (p. 47) suddenly confessed to me in a whisper as I was taking her picture in her home in Maringa in the state of Parana.

Yoshimitsu Nakamura (p. 146), the 72 year old Chairman of the Japanese Society of Bauru in the state of Sao Paulo, made the brief comment, “I only finally reached the decision to be buried here in Brazil when I held my blue-eyed grandchildren for the first time.”

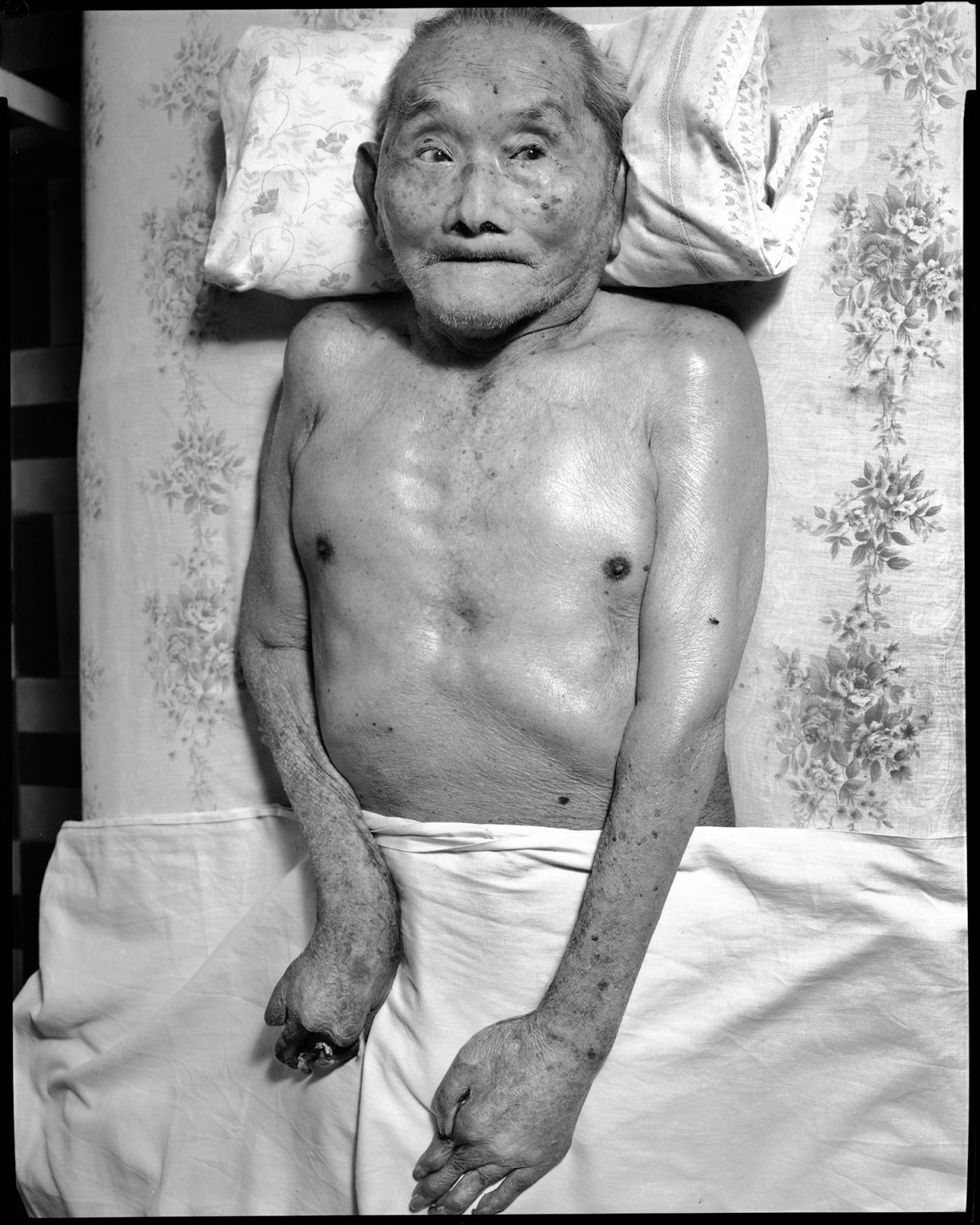

Ninety-five year old Naoe Sonoda (p. 90, 91) was silent ; he could not say anything to me. A resident of Recife in the state of Pernambuco, he was one of the last remaining of those who immigrated aboard the Kasato-Maru. He did not even blink when my huge 8 x 10 inch Deardorff camera was fixed directly over his bed. Though aware that I was being rude, I impudently pressed down on the shutter.

“There are pines, bamboo, and plum trees, as well as wild cherry trees. An arched bridge lies in the center, and Mount Fuji can be seen in the distance,” said 91 year old Ichiro Hironaka (p. 100) of Lima to describe the painting on his living room wall which apparently depicted a dream of his.

I was taking a commemorative photograph of him with the dream picture in the background.

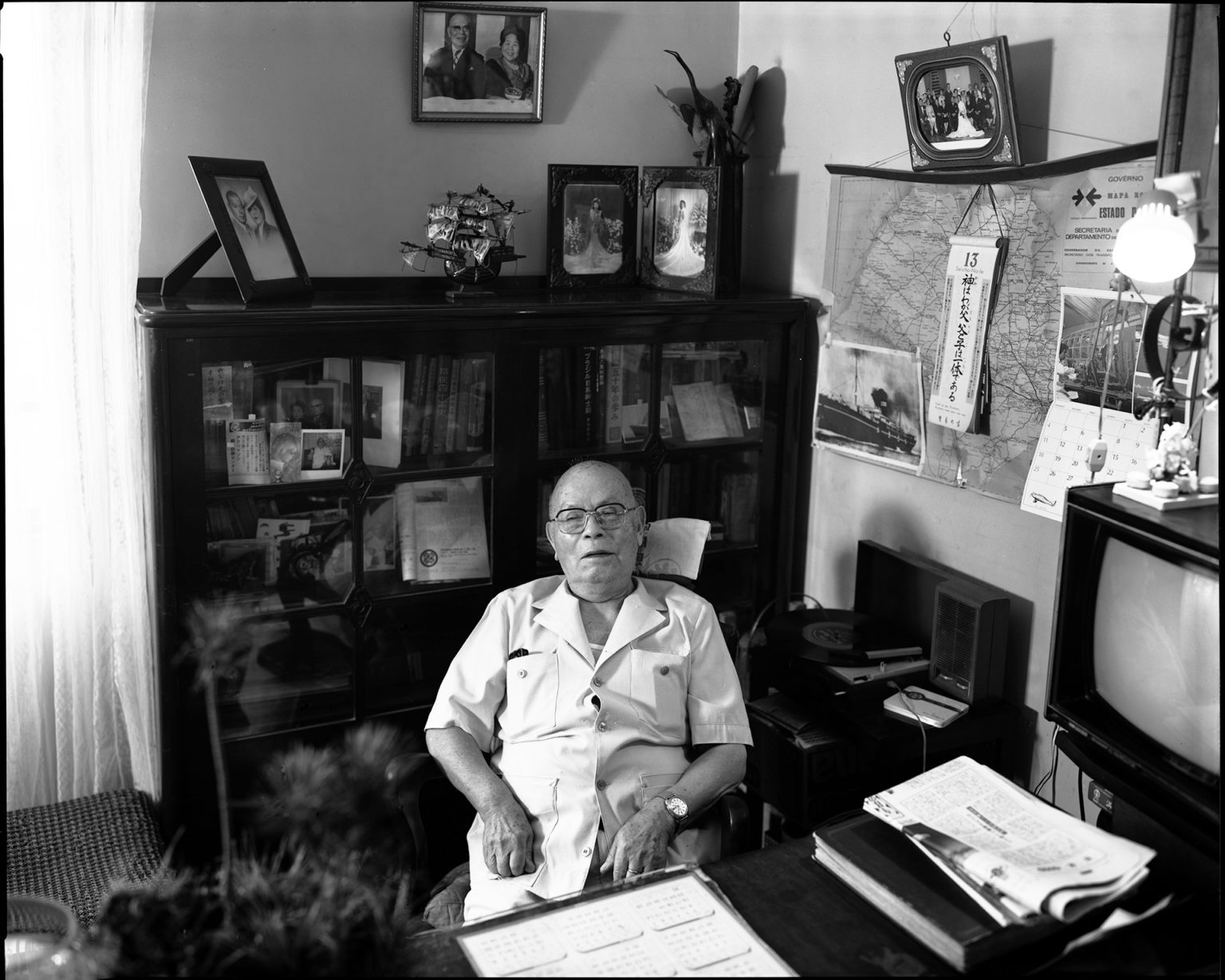

“I don't need a photo. Let's just talk. I really don't need a photo,” said eighty-nine year old Johei Isuda (p. 112).

Then once I finally finished shooting, he asked how much he should pay for the photographs. A barber in downtown Lima,

Tsuda was once an extremely popular figure, nicknamed"Chaplin.” However at the time I met him, due to the infirmities of old age, he was no longer capable of using a razor, an important tool of his trade. Yet even though he was not getting any patrons lately, he was still donning his white uniform every day.

“Chinese people would stick to all the money they had. And when the odds were just about nil, they would simply go home. We Japanese are different. We kept on waiting for a better turn in the tide, while getting stripped of everything,” remarked 88 year old Shigeo Kanda (p. 119), the only Japanese “issei” in Guayaramerin, which takes one day and night by waterway from Riberalta, the terminus for the over one thousand (estimated) Japanese who flowed in from Peru.

The main street of the town of Guayaramerin overflows with gambling houses. The three themes of "drinking,” “striking for luck" and "buying" seem to have a devilish appeal. This intensely hot region near the source of the Amazon also appears to serve as a heroin smuggling route.

"In 1935, I launched my Kabuki career playing Ishido Maru, and took my final curtain call in 1968 as Nezumi Kozo, the "Mouse Accolyte," commented Mitsuishi Takeno (p. 148). An 87 year old resident of Bastos in the Sao Paulo state, he also goes by the stage name of Kikusho Onoe. The supervisor of the Hakuko Drama Troupe, Onoe had been extolled by the “issei” immigrant community as a master of rapid transformation. At the time I met with him, he was quietly living out his post-retirement years in the spot which had been as the headquarters for his theatrical troupe for over four decades.

“I came to Brazil as an immigrant farmer, but now I'm the top fisherman in this country. After undergoing extremes, a person can do anything. During the war, I was put into an internment camp in California. But I managed to get by because I have all this strength,” stated Toshimatsu Ono (p. 152) with a smile as he drew his "nisei” wife over to him by her shoulders. Eighty-four year old Ono owns around 15 or so tuna boats and the like. He is the “don” of the port of Santos.

The living room of a typical “issei” household I visited in Sao Paulo had a slight air of confrontation as shouts of “Viva, Viva, Braziliero” were emitted. The great-grandparents in their eighties were gloomy and silent. A “nisei” in his sixties emitted a series of “Viva" shouts as he drew his "yonsei” grandchild onto his knees. This man's eldest son, a "sansei” in his thirties, who could not speak Japanese, grinned awkwardly, avoiding my eyes. This trifling scene took place when the national volleyball team of Japan went on a playing tour of Brazil in the middle of March, 1984. Since all the matches ended disastrously for the Japanese team with a set count of zero, the “issei” members of the family apparently had confused, mixed feelings at the time.

“Let's make a silent prayer,” reverberated the low yet severe voice of 76 year old Kinsuke Minowa (p. 36, 145) in the common dining room. Then a chorus of about 40 or 50 voices shouted in unison, “Let us partake now.” The people live and work communally on the Yuba Farm in 3 Allianca in the Sao Paulo state.

The Yuba Farm's ideal is to have agriculture and farming function like two wheels of a cart. Almost all the people on the communal farm participate in its ballet performances which have gained fame throughout Brazil.

“Here rest the souls of the Japanese ‘issei' who dedicated themselves to the Brazilian nation. People of Japanese descent played an especially key role in the settling of this region. However times have changed, and so has farming. Thus, the onetime residents of this area have dispersed all over Brazil. But many of the people I miss return here once a year for O-bon (the festival of the dead),” explained 90 year old Ryoichi Kodama (p. 34). He was decked out in a “happi" coat for “bon” dancing when we spoke at the plaza in Alvares Machado, Sao Paulo, where an abandoned Japanese school lies.

The countless number of graves bearing Japanese names lined up on a gentle hill were serenely bathed in the early autumn dusk. (p. 80)

I have a feeling that I have just finished relating about half of my role through this recording of the words of nostalgia for Japan coming from the people who left a particularly strong impression on me during my three calendar years gathering stories in South America. I also carried out surveys and assignments in Hawaii and the North American continent during these past three years. In any case, this work would not have succeeded without the immense help of Toshinori Ebina, President of Office Two One, Ltd., who lent me an ear from the very planning stage. Moreover, in closing, I would like to express my thanks to the staff members of Office Two One who accompanied me on part of my journey in South America in order to do some filming for a television documentary project.

English Translation / Lora Sharnoff