AMERICA/PROMISED LAND

The Museum in Urashima Taro's Box

Of all the folktales of my childhood, the tale of Urashima Taro whispers most closely in my inner ear such that when I received the package of ARAMASA Taku’s photography from Tokyo, I left it unopened on the table for most of a day, shuffling and rearranging books and papers around it perhaps to savor the wonder there contained but also to rub away the foreign address embedded in its postage. Ah, but curiosity.

My premonitions, however, were correct, and as I turned the pages of this photographic geography in large sweeping arches of black and white movement and contemplation, I became lost in memory and forgetting, at once youthful and aged, a child of senility. I was aware of having entered a kind of museum, a place of history deeply personal to myself yet displaced by a sad and timeless beauty. I had entered the world inside ARAMASA Taku’s camera. I had entered the museum in Urashima Taro’s box.

Sometime in the early 1990s when the Japanese American National Museum was getting its start, I remember a conversation with my friend Chris Komai who was involved in planning for the new museum to be situated in Little Tokyo, Los Angeles. He explained to me that the fledgling museum had already begun to receive archival and historic artifacts donated by members of the community.

June 2000

The interesting problem was how to evaluate the historic value of any artifact. Presumably there were paper documents, journals, photographs, articles of clothing, handmade and artistic work, but also perhaps mundane objects that survived the camps — utensils, polished driftwood, old dolls, a baseball bat, pressed flowers. How should one make a judgment about an article of sentimental value? What meaning would a particular artifact have placed behind glass, carefully lit, and documented with an explanation and a date? Why should the museum choose to preserve and keep one artifact and not another? I tucked these questions away, assuming there to be a science of the museum; a museum curator must know the answers to these questions.

At the same time I was reminded of the Museu Historico de Imigração Japonesa no Brasil located in São Paulo City's equivalent of Little Tokyo, the Liberdade. This museum had already been open and functioning for some time, and I had probably visited it for the first time in 1975. It contained a photographic and documentary exhibit of early Japanese immigration to Brazil, replicas of early housing for contract laborers on coffee plantations, including tools and furniture, as well as the paintings and drawings of Tomoo Handa, known for his extensive historic work detailing that immigration. At the end of the exhibit I also recall an aquatic tank with an electric freshwater eel, perhaps to demonstrate one of the exotic species of wild life found in the Amazons but most likely one of those donations that a community museum might necessarily absorb into its collection. Perhaps I am mistaken in my memory of this; the upkeep of a live animal in such a museum seems now to be rather difficult if not improbable. In any case, if there were an Amazonian eel, there might also have been an exhibition of the various insects, birds and mammals, all equally exotic for the Japanese immigrant newly arrived in Brazil.

Again, the question about what should be placed inside a given museum for safekeeping, memory and display tweaks the imagination. For whom does such a museum exist? Is a museum, like the American Smithsonian, an attic for our discarded junk, curiosities that remind us of the past, of a modernity that is no longer modern, the proof of life experienced, of the relentless passage of time?

In Los Angeles, there is a curious museum written about in a book by Lawrence Weschler entitled Mr. Wilson's Cabinet of Wonder. The Museum of Jurassic Technology is a kind of installation that challenges our notion of the museum and its reason for being, revealing the origins of the museum in the desire of the private collector to gather and organize a collection of oddities, antiques or natural objects.

One small section of the museum is dedicated to the work of Geoffrey Sonnabend, a scholar who, according to the details presented in the exhibit, developed a theory of forgetting. The audio-visual portion of this exhibit demonstrates Sonnabend's ideas graphically in the form of what is called the “Cone of obliscence” and the “Plane of experience” which intersect to create brief but after all ephemeral and inevitably illusory memory. The wonderful irony of the exhibit is contained in the collected artifacts said to belong to the theorist, including audio from an opera he would have attended. Marvelous to me is the encased miniature panorama of the Iguaçu Falls, one of the most extraordinary natural sites located at the very corner of Argentina, Paraguay and Brazil where Sonnabend presumably experienced the epiphany of his idea. If Sonnabend thought of a theory of what might be called anti-memory, the museum's exhibit is the most elaborate and arcane tribute to the memory of the man himself.

When you emerge from the museum squinting in the daytime sunlight, you find yourself on the busy working class street of Venice Boulevard, as if you have emerged from a time-warp or the dark memory inside another brain. Quickly you run down the street to the Cuban restaurant Versaille or the Café Brasil and contemplate the Foz de Iguaçu inside a demitasse of strong espresso. The cone of obliscence has wiped your slate clean again.

The museum is a project of memory in which artifacts are preserved and, although removed from their locations and time periods, furnishes a way back to the past. The museum is a project of choosing to remember as well as choosing to forget. Perhaps the museum itself is the very intersection of obliscence and experience, an intersection where memory is briefly caught.

The photograph, like the museum, can be an act both of memory and erasure, an artifact that captures an exact moment in time, a moment which in its exactitude defines and defies every other moment before and after, erases the minute and myriad, gentle and dramatic, changes that construct the exact moment of exposure, erases the continuing passage of time as we walk away from the moment of the photo itself and every succeeding viewing into the future.

Vanishing Landscapes

Urashima Taro saves a great turtle, an ageless turtle, who cannot understand the nature of human time, cannot understand Urashima's confusion as he returns from his underwater adventures to his seaside village. Where is the house where he was born? Where are the familiar markers, the neighbors, his mother's garden?One of my favorite books about Japan is a compilation of oral histories of the oldest inhabitants (born between 1889 and 1917) of the town of Tsuchiura in Ibaragi Prefecture, transcribed by a physician named Saga Junichi and published in English translation in 1987. The title of his book is Memories of Silk and Straw: A Self-Portrait of SmallTown Japan. These stories reveal the long-gone livelihoods and physical surroundings of townspeople such as tofu and sembei-makers, fishermen, gangsters, horsemeat butchers, and even executioners in the 1910s and 20s. By this time, my own grandparents had established their lives in San Francisco or Oakland, California, but I imagine that the Japan they knew as children might not have been so different. What struck me when I first read this book was the incredible change and difference of that old world remembered only 60 years later. Never again, for example, would we experience tofu sold from wooden buckets balanced on a pole over a man's shoulder. The Japan of my grandparents had all but disappeared. The tale of Urashima Taro was true.

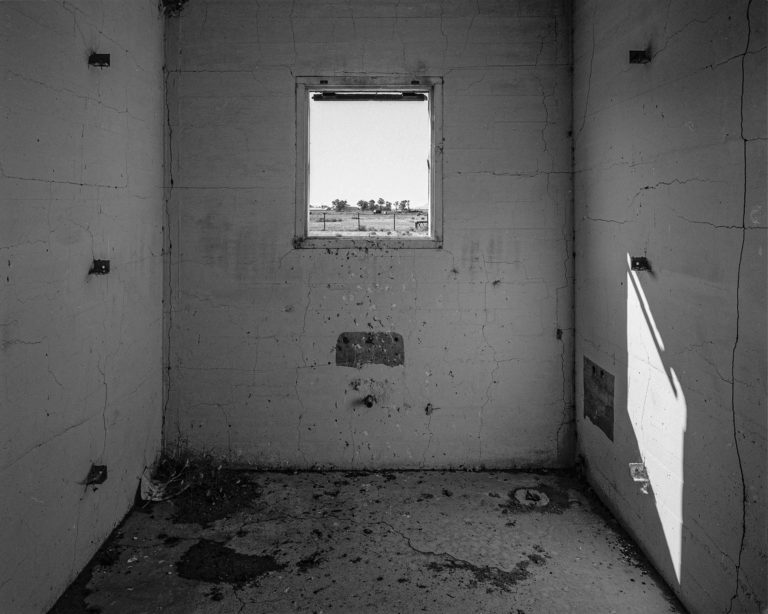

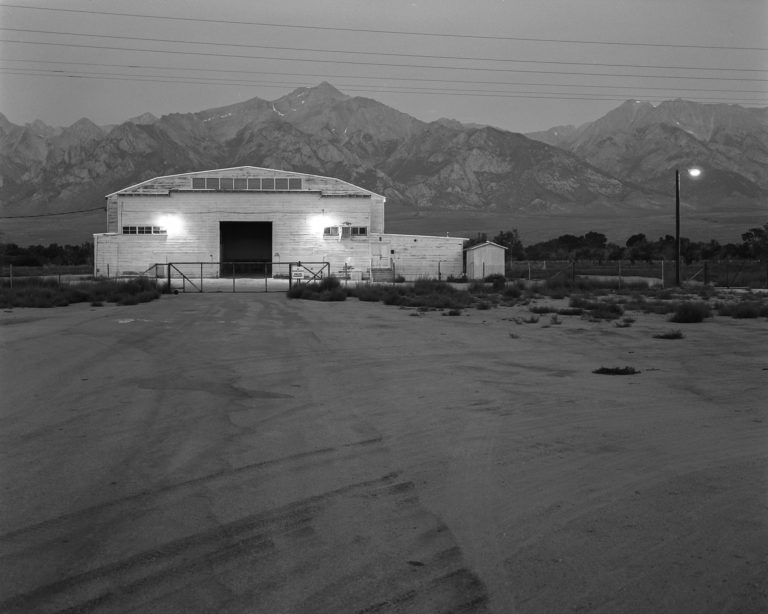

Similarly, it is as if a great turtle has left us within the pages of ARAMASA's photography to contemplate a deserted village, once teaming with human community. There is an unsettling beauty in these landscapes of vanishing wartime internment camps. If you are a sansei like me who was born after the war, you begin to wonder about the stories you have heard and collected and the erasure of human history across an unfeeling natural landscape. If you are a nisei like my mother who was interned at Topaz Internment Camp in Utah, you look on the desolation of the land where you, your family and thousands of Japanese Americans lived during the war and acknowledge the land’s inhabitability — a place like the moon fit only for exile, badlands stolen long before from indigenous peoples, further tainted by your loss and suffering. No one since has wanted to live again in such places. Where did the water and the electricity come from? What cunning could so quickly build a prison around innocent people and then all but disappear? How, you wonder, can we have been so hated, so feared, mistreated and abandoned?

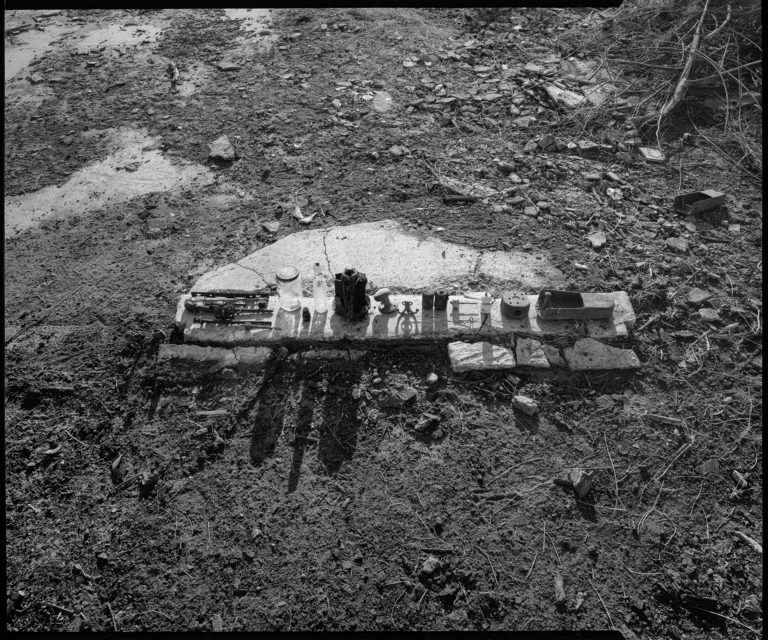

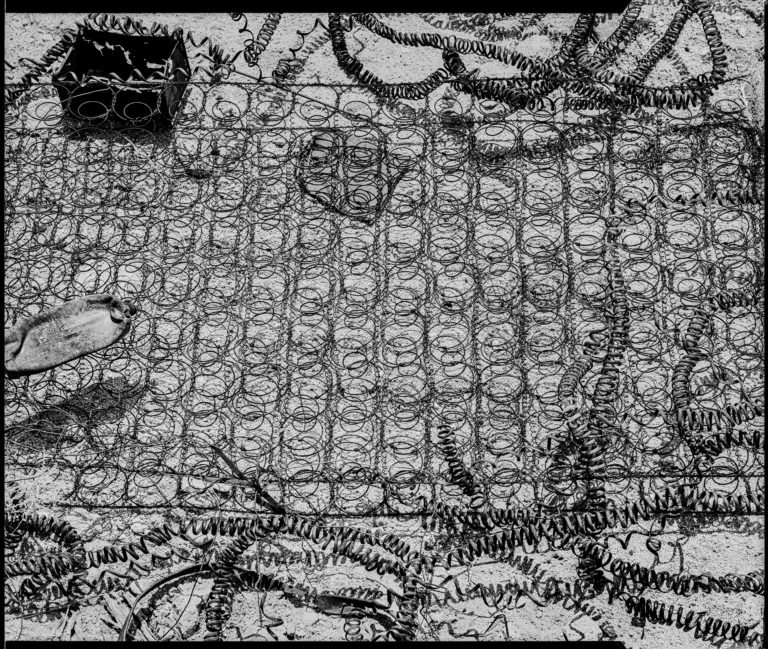

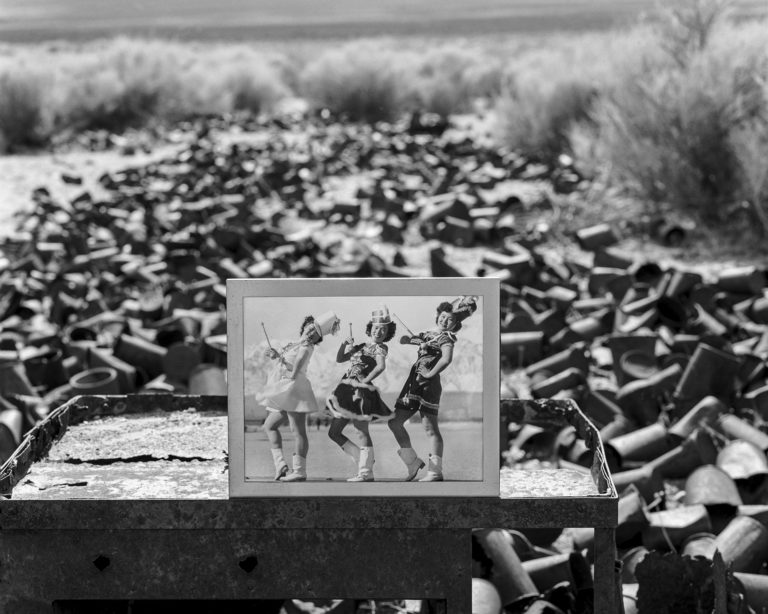

ARAMASA's landscapes are interrupted by ruins and artifacts: the crumbling foundations of barracks; the stonework of a dried out garden pond; a group of tombstones with names like Kinoshita, Takade, Kunitomi; a field of rusting cans; an arrangement of castaway bottles and metal objects; a door knob, nails, hinges; a Japanese doll, old geta. Within a few of the scenes, ARAMASA includes work by Miyatake Toyo, an issei photographer known for smuggling his camera into the Manzanar Internment Camp. Thus, a framed photograph by Miyatake sits on a tree stump, the great Sierra Nevada in the background. Miyatake's image of young boys staring out through barbed wire that stretches back to a distant guard tower returns momentarily to haunt this horizon. It is not just the framed image; the young boys themselves return and so does Miyatake Toyo. One imagines the photographer risking a moment on the opposite side of the barbed wire, the shadow of his camera and his own body cast against the rocky soil. And then there is this second moment, some fifty years later when ARAMASA Taku's camera and body too are cast in shadows we can only imagine over the same spoiled earth.

From Saga Junichi's Tsuchiura to Miyatake Toyo's Manzanar to ARAMASA Taku's landscapes of Japanese America, Meiji to Heisei in one hundred years, how much is changed, how many ways of living abandoned and forgotten. Punctuating the center of these years was the violent event of war — lives divided by hatred and killing, and to have lived them all is a small miracle of survival and obstinacy.

Centenarians

The essence held in Urashima Taro's box is the process of human growth, maturing and aging — Shakespeare's seven ages of man, from puking infant to second childishness. Here, ARAMASA Taku conjoins landscape and portraiture such that all of the photographs depict landscape, whether of the land or of the human body, and all of it vanishing, disappearing wartime internment camps but also the bodies of issei centenarians in the very process of erasure and forgetting. Like the ruins of these American sites of imprisonment, the one hundred year-old body is another kind of ruin, a living museum, clothed and surrounded by the artifacts that mark time and place, individual stories and sentimental worth. The mind does a strange trick, superimposing portraits of issei and nisei on the landscapes they once inhabited. Like Miyatake's photographs within photographs, these portraits conjure memories, return as dogged witnesses to events even as the remains of these sites and their bodies have been captured on film perhaps for the very last time, the very edge of absence, erasure, death. Their bodies inscribe the landscape with a history of human existence. What are missing then are their voices. They stare at us from their posed moments, their old bodies speaking a great silence. Speak! I want to say. Where is Saga Junichi now? Who will transcribe their stories? How to conjure words? What words to conjure?Voices

Of course the tale of Urashima Taro begins with mukashi mukashi, but my memory encounters the word: Abunai! This may have been one of the first Japanese words I learned. My mother could never explain why in a moment of great distress and the need to protect me from danger, the only words that she could successfully utter were Japanese. Instinctually, abunai was the word that summoned the command that would protect me from harm. I would hear it and know it from a deep past that belonged to her and to her own mother as well.Ii ko ne. These are words that my cousins and I all associate with our Tei obaachan who did not speak a word of English. We were all good children, and if Tei, whom everyone regarded as wise in her old age, could say such words, they must be true. I remember my maternal grandmother to be a small woman with the protruding chin and malocclusion that has marked all of us progeny, her spine folded over, her thin white hair combed into a tiny bun at the base of her head. In the summers, my family visited Tei who lived above the family fish market and grocery in an old Victorian house of high ceilings on Post Street in Japantown in San Francisco. My grandfather and, thereafter, my uncles and aunts, had run the Uoki Fish Market since the 1900s. Sometimes I slept next to Tei in the large double bed in her room overlooking Post Street.

She was so slight and quiet, I barely felt her presence, and she slipped away from the bed every morning as soon as it was light. While the night below on Post Street was filled with the distant sounds of jazz and human carousing, the early morning hours faded into the commotion of unloading produce from trucks, my uncles yelling orders back and forth, their feet stomping up and down the long staircases to retrieve boxes of imported Japanese foods — dried bonito, sembei, nori. I followed Tei's bent figure through the old house, down the long staircase, observed her daily ritual before the Buddhist altar with the stern photo of my grandfather, watched the thin trail of smoke from incense that followed the long reverberations of the chime, then followed her through the kitchen, down the back stairs into the back entrance of the fish market, past the cold breath of the refrigerator and the stink of fresh fish. I watched her reach for frosted flakes and the green and yellow packets of something I knew as ochazuke.

My mother wouldn't approve of the all the sugar on the corn flakes, nor the salt in the ochazuke, but Tei obaachan never gave it a thought. I would indulge myself for breakfast and lunch. This was the luxury of having your very own grocery store right under your house. While I slurped up ochazuke from my ochawan, Tei sat hunched over at one end of the large kitchen, her gnarled and wrinkled hands constantly in motion, crocheting a blanket.

Minna! Katta! My father was always a great and avid competitor at games, and his wild enthusiasm gave every act of play a special life. One summer while camping he taught us to play poker, hardly a very orthodox activity for a Christian minister, but he was never orthodox. In any case, we played for pebbles collected in the riverbed. He loved to tease us with his great bluff. He bet everything, pushing his great mound of pebbles to the center of the card table. Minna! he roared so that his mother who had joined us for the summer would roll her eyes. We all dropped out like frightened flies only to have him reveal his poor hand. Katta! he would yell into the redwoods.

My paternal grandmother Tomi spoke what she called broken English, lived alone in a small apartment in Berkeley on San Pablo Avenue, and came to visit and live with us from time to time. If Tei was obaachan, Tomi, given her broken English, was always gramma. Her husband had been a tailer, schooled in New York. He opened the Yokohama Tailor Shop in Oakland where my grandmother must have also learned to sew. She was always well dressed with hat and gloves — elegant and vain. Proud of her figure and posture, for much of her life she wore a corset laced down the middle.to make it tight. When you hugged Tomi, you could feel the stiff corset around her torso and the little hooks sometimes digging into your chest. She'd tell me that I was very pretty like my aunt, her first daughter. who in turn also resembled Tomi herself when she was young. She made me think that I was part of a continuing line of beautiful women. Always curious about her activities, I watched her fill her fountain pen with blue ink, scroll kanji down the pages of her letters, and carefully use a blotter to prevent smears.

Maybe she ended her letters in kamisama no okage de. She had been converted to Christianity probably in Tokyo by Christian missionaries, and she had a large group of issei friends who all attended the same church. Sometimes I sat next to her on the sofa while she prayed and then fell asleep. She was a great snorer, and at night you could hear the sound of her guttural roar penetrating the walls.

She died while I was a student in Tokyo where I practiced my kanji and sent her letters in Japanese. Perhaps by then she was too ill to my broken Japanese. My father wrote me from Oak Park, Illinois, where he and his sisters nursed her until she died. He wrote to me saying that every day gramma awoke in surprise and announced, mada ikite iru?

Abunai. Ii ko ne. Minna! Katta! Mada ikite iru? First words to last words, words that for me lose their emotional grip in any other language. Within them, voices return to me — the high pitch of my mother's greeting, Tei's low chuckling tones, my father's exuberance, Tomi’s exasperated dignity. My grandmothers both lived a decade short of a hundred years. Carved into their faces and hands, their sagging breasts, bowed spines and bunioned feet, was an entire landscape of history and experience. But it all happened so quickly. How were they to know in 1900 when they arrived in America that a war would interrupt the very middle of their lives, would disperse their children and destroy their dreams? Why had they and other women come so far to suffer the frustrations of unsuccessful men, to raise their families through a Great Depression, to see their children imprisoned or sent to war to die? Who could read the intricate landscape of their bodies, that silent map, the inscription of their lives? Ii ko ne. Mada ikite iru? Their voices waft over the landscape, haunt the ruins, swirl around artifacts, breathe life and story into our museums of memory and forgetting.

The Future in a Camera Box

Can the future exist without the past? Why not? If time is an inevitable continuum moving on, unstoppable, surely the future just happens. But, if the future is also what we imagine, then the past and a memory of that past must exist to build such a future. Some, like Sonnabend, would say that memory is illusory, imagined. And so it is.Memory can be a kind of story we tell about past events. Some of it we imagine. We do our best to remember, to tell the truth, but sometimes the truth doesn't always make such a good story. And there is memory that hovers over any story, inexplicable memory: the salty stink of shoyu, the texture and weight of my father's hand on my forehead, the shape and dance of light over kelpy waters, the sound of the sheen as its glistening disappears into porous sand and crumbling seashells. An ancient Urashima Taro at the edge of the ocean. Does he look through the camera box or is the camera box focused on him? Or is he anyway a pile of ashes within that very box? It all happened so fast — an impossible dream, but ARAMASA's natural and human landscapes are here to tell you that it really happened. Fleeting evidence but evidence. A great gift of dying that charges the freedom of the future.

Karen Tei Yamashita

June 2000

浦島玉手箱博物館

子供のころ聞いたすべての民話の中で、私の心の耳にもっとも親しくささやきかけてくるのは浦島太郎のお話だ。それで新正卓の写真の入った小包が東京から送られてきたとき、私はその日ずっとそれを開けることなく、本や新聞や書類を無雑作にその上に積み重ねたり並べ変えたりしながら、テーブルの上に置きっぱなしにしていた。それはたぶん包みの中の驚異への期待を楽しむためであり、またたくさんの切手に埋もれかけた外国の住所がこすれて読めなくなるようにするためでもあった。ああ、でも人は好奇心には勝てない。

それでも私の予感は正しくて、このモノクロの運動と熟視の、大きく旋回するいくつもの弧が描き出す写真地理学のページをめくるにつれ、私は記憶と忘却の中に迷いこんでしまった。若くて、同時に年老いた、老齢の子供として。一種の博物館に自分が入りこんでいることに、私は気づいた。それは私にとって深く個人的な歴史の場所、けれども、ものさびしい無時間的な美に置き換えられている。私は新正卓のカメラの内部の世界に入っていた。浦島太郎の玉手箱博物館に、入ってしまったのだ。

1990年代初頭、日系アメリカ博物館が設立準備に入ったころのこと、ロス・アンジェルスのリトル・トーキョーに開かれるこの新しい博物館の計画にたずさわっている友人のクリス・コマイと交わした会話を、私は覚えている。まだ雛鳥でしかない博物館だが、すでに日系社会の人々から資料や歴史的物品の寄贈を受けはじめているということを、彼は話してくれた。

カレン・テイ・ヤマシタ/2000年6月

管 啓次郎・訳

このとき厄介な問題は、どのようなものであれその物品の歴史的価値をいかに評価すればいいのか、ということだった。たぶん、書類、日記、写真、衣類、手工芸品や芸術作品などがあるだろう。でもそれだけではなくて、強制収容所(キャンプ)生活を経験してきた、日用品もあるだろう ⸺ 道具類、磨かれた流木、古いお人形、野球のバット、押し花など。心にとって思い出としての価値をおびた品々を、どう評価すればいいのか?

ある特定の物品が、ガラスのむこうに注意深く照明をあてられ説明と日付けを添えて置かれたとき、どんな意味をもつことになるのか? なぜ博物館は、ある品物を保存することを選び、別の何かは捨てなくてはならないのか? 私はこうした問いを棚上げにしてしまった。博物館学とかいうものがあるのだから、と思って。専門の学芸員が、こうした問いに対する答えを知っているにちがいないのだから。

またこのとき私は、ブラジル日系移民博物館のことを思い出してもいた。それはサン・パウロにおけるリトル・トーキョーとでもいえる、リベルダージ地区にある。こちらの博物館はすでにしばらくまえに開館され活動してきたもので、私がそこをはじめて訪れたのは1975年だったと思う。そこにはブラジルへの初期日系移民の写真と資料が展示され、コーヒー農園の契約労働者たちが最初の頃に住んだ住居の複製が道具類や家具とともに置かれ、移民・入植の細部を描いた膨大な歴史的作品で知られる半田知雄の絵画やスケッチが掛けられていた。展示の最後には、電気ウナギを入れた水槽があったのを覚えている。これはアマゾン河流域地方のエグゾティックな野生動物を見せるためだったのだろうが、おそらく移民社会に根ざした博物館にはどうしても断ることのできない、寄贈品のひとつだったのではないか。それともこの記憶は、私のまちがいなのかもしれない。このような博物館で生き物を飼うのは、いま考えてみると、ありえなくはなくとも、かなりむずかしいことだろうと思えるので。いずれにせよ、アマゾン河のウナギがいたのであれば、またいろいろな昆虫や鳥や哺乳動物といった、ブラジルにやってきたばかりの日本人移民にとってはどれもおなじようにエグゾティックだった生物たちも、展示されていたかもしれない。

またもや、ある博物館には保管、記憶、展示のために何が置かれるべきなのかという問いが、想像力を抓る。そうした博物館は、誰のためにあるのか? 博物館というものは、アメリカのスミソニアン博物館のように、われわれが捨てたがらくたを所蔵するための、過去やもはや古びてしまった現代や生きられた生活の証拠や時間の容赦ない流れを思い出させてくれる珍奇な事物を片付けておくための、屋根裏部屋にすぎないのだろうか?

ロス・アンジェルスに、ローレンス・ウェシュラーが『ウィルソン氏の驚異の陳列室』(みすず書房、1998年)という本に書いた、奇妙な博物館がある。ここジュラシック・テクノロジー博物館は、私たちが抱く博物館の観念とその存在理由に挑むような一種のインスタレーション作品で、奇怪なものや古いものや珍しい自然物を集めコレクションとして組織したいという個人蒐集家の欲望こそ、博物館の起源にあるものだということを、明らかにしてくれる。

この博物館のある小さな部屋は、ジェフリー・ソナベンドの仕事にささげられている。展示の紹介によると、彼は忘却の理論を展開した学者だそうだ。この展示の視聴覚資料が、ソナベンドの考え方を説明してくれる。「記憶喪失の円錐」というものがあって、それが「経験の平面」と呼ばれるものと交わり、簡潔な、けれども結局は、あまりにもはかない、不可避的に幻想でしかない記憶を生み出すというのだ。この展示のすてきなアイロニーは、この理論家が所有していたとされる数々の収蔵品 ⸺ そこには彼が劇場で見たと思われるオペラ作品の録音も含まれる ⸺ に見られる。私にとってすばらしかったのは、イグアスの滝のケース入りミニチュア・パノラマだ。イグアスの滝は世界でももっとも驚異的な自然景観のひとつで、アルゼンチン、パラグアイ、ブラジル三国の国境に位置し、どうやらソナベンドはここで彼の着想の啓示を経験したようだった。ソナベンドが考えたのが反=記憶とでも呼べるものの理論だとしたら、この博物館の展示は彼自身の記憶への、もっとも精緻な、秘められた賛辞だった。

この博物館から、日中の陽光に目を細めながら出てくるとき、あなたはタイムワープか他人の脳内の暗い記憶から出てきたような気分で、ヴェニス・ブールヴァードの人通りの多い、労働者階級の街路を歩いている自分を発見することになる。通りをそのまま歩いてゆくとすぐに、キューバ・レストランのヴェルサイユやカフェ・ブラジルにさしかかり、そこでデミタス・カップの濃いエスプレッソの中に、イグアスの滝を見つめることになるのだ。そうしているうちに記憶喪失の円錐が、またもやあなたの記憶の石板を、きれいに拭い去ってくれる。

博物館とは記憶のプロジェクトだ。そこでは蒐集物が保存され、本来の場所や時代からは遠ざけられているにもかかわらず、過去に戻る道を人に提供してくれる。博物館とは記憶することを選ぶプロジェクトだが、また忘却することを選ぶものでもある。おそらく、博物館そのものが、忘却と経験の交錯する点、記憶がつかのま捕捉される一点なのだ。

写真もまた、博物館とおなじく、記憶と消去という背反する二つの行為なのかもしれない。それは、時間の中のある厳密な一瞬間を捉えるものであり、提えられる瞬間は、その厳密さにおいて前後のすべての瞬間を画定し、またそれらを平然と無視する。露出の瞬間を構成する細密で無数の、微妙でドラマティックな変化が消去される。同時に、撮影の瞬間からわれわれが歩み去っても、未来において写真を見るたびごとに、時間の絶えざる流れは廃棄されるのだ。

消失する風景たち

浦島太郎は一頭の大海亀を救った。計り知れないほど歳をとった亀で、人間的尺度の時間を理解することができず、海底での冒険から海岸の村へと帰った浦島の混乱を理解することができなかった。自分が生まれた家はどこなのだろう? 見なれた道標、近所の人々、母の庭はどこなのだろう?日本について書かれた本で私がいちばん好きなもののひとつに、茨城県土浦の最年長の老人たち(1889年から1917年生まれ)に聞いた話を、佐賀純一という名の医師が転写しまとめたものがある。英訳が1987年に出版されていて、題名を『絹と藁 ⸺ 小さな町に見る日本の自画像』という(日本語版は『田舎町の肖像』、図書出版社、1993年)。ここで語られている話は、町の人々の、いまでは姿を消してしまった生活や物質的環境について教えてくれる。豆腐屋にせんべい屋、漁師、やくざ、馬肉屋、さらには1910年代、20年代の死刑執行人までがいるのだ。このころには、私自身の祖父母はカリフォルニア州のサン・フランシスコやオークランドに生活を築いていたのだが、かれらが子供時代に知っていた日本は、この本に語られている日本とあまりちがわなかったのではないかと、私は想像している。はじめて読んだとき、私が衝撃を受けたのは、たった60年後に回想されるその古い世界と現代の日本とのあいだにある、信じられないほどの変化と差異だった。たとえば、男が天秤棒で木橋を肩にかついで売りにくる豆腐に私たちが出会うことは、二度とない。私の祖父母の日本は、ほとんどまったく姿を消してしまった。浦島太郎の物語は、本当だったのだ。

それとおなじように、大海亀は私たちを新正の写真集のページに置き去りにしてしまったようだ。かつては人々が生き生きと暮らしていた村の、見捨てられた後の姿を見つめるために、いまや失われつつある、これら戦時中の強制収容所の風景には、人を不安にさせる美が立ちこめている。もしあなたが私とおなじく戦後生まれの三世だったなら、あなたはあなたが聞いたり集めたりしてきた数々の話について、この無感情な自然景観いっぱいにひろがる人間の歴史の消去について、いやでも考えはじめるはずだ。もしあなたが私の母とおなじくユタ州のトパーズ強制収容所に入れられていた二世だったなら、家族やその他の何千人という日系アメリカ人とともにあなたが戦争中の暮らしを営むことになった土地の荒涼とした風景を見て、この土地に人は住めないということを再確認するはずだ ⸺ 流浪者のみにふさわしい月面のような場所、遠い昔に先住民から盗みとられた荒れ地、しかもあなた自身の経験した喪失と苦痛によってさらに染め上げられた土地。それ以後、そんなところにふたたび住みたいと願った者は、誰もいない。水と電気はどこから引かれていたのだろう?

いったいどんな狡知によって、罪もない人々の周囲にあれほどすばやく牢獄が建てられ、ついでほとんど痕跡もないほどに消失したのか? いったいなぜ、とあなたは不思議に思う。われわれ日系人はあれほどまでに憎まれ、恐れられ、虐待され、見捨てられたのか? 新正の風景には、数々の廃虚と異物がちりばめられている。仮設住居の、崩れかけた土台。干上がった庭池の石組。キノシタ、タカデ、クニトミといった名前のある一群の墓標。一面に転がる錆びた空き缶。捨てられた瓶や金物が並ぶかたち。ドアの把手、釘、蝶番。日本人形、古い下駄。いくつかの場面に、新正は宮武東洋の作品を取り入れている。マンザナー強制収容所にひそかにカメラを持ちこんだことで知られる、一世の写真家だ。それで宮武が撮った写真が枠に入れられて、大いなるシエラネバダ山脈を背景に木の切り株に置かれている、というわけだ。遠い見張り塔までずっと続く鉄条網から外を眺めている少年たちを撮った宮武の映像が、一瞬戻ってきて、この地平にとりつく、枠の中の映像だけではない。少年たち自身が帰還し、宮武東洋が帰ってくるのだ。危険を冒してつかのま鉄条網の反対側に出て、彼のカメラと彼自身の影を石ころだらけの地面に投げかけている写真家を、たしかに想像することができる。ついで、この第二の瞬間、およそ50年後に新正卓のカメラと体がまた影となって、おなじ荒れはてた土地に投げかけられている様子も、私たちにはただ想像するしかないことだ。

佐賀純一の土浦から宮武東洋のマンザナーから新正卓による日系アメリカの風景まで、明治から平成にいたる百年のあいだに、どれほど多くが変わり、どれほど多くの生き方が捨てられ、忘れられたことだろう。これらの年月の真ん中に読点を打っているのは、戦争という暴力的事件だった ⸺ 憎悪と殺害によって分断された数々の人生。そしてこの長い年月をずっと生きてきたということは、執拗に生き延びようとする意志だけになしとげることができた、小さな奇跡だ。

百歳を超えた人々

浦島太郎の玉手箱に閉じこめられている本質とは、人間の成長のプロセスにほかならない。つまり成熟し、歳をとってゆくことだ ⸺ シェイクスピアのいう人間の七つの年齢、乳を吐く赤ん坊にはじまり第二の子供時代にいたるまで。ここで、新正卓は風景と人物の肖像をひとつに結びつける。すべての写真は、それが土地であれ人間の身体であれ風景を描きだすものとなり、しかもそのすべてが消え去りつつある。消滅しつつある戦時の強制収容所跡、そしてまさに消去と忘却の途上にある、百歳を超えた一世の老人たちの身体。アメリカ国家による監禁の場所の廃虚とおなじく、百歳の身体は別種の廃虚、生きた博物館であり、時と場所、個別の物語や感情的価値を刻まれた事物を、身にまとい、あるいはそれらに囲まれている。心とは不思議な技を使うもので、一世と二世の肖像を、かれらがかつて住んだ風景に重ねてみせるのだ。写真の内部に置かれた宮武の写真とおなじく、これらの肖像は記憶を召喚し、これらの場所や身体の廃虚の記憶を不在、消去、死の間際において捉えながら(おそらくそうして捕捉=撮影されたのはそれが最後だったのかもしれない)、さまざまな事件に対する頑迷な目撃者となるのだ。かれらの身体は、人間の存在の歴史を、風景に記入する。そのとき欠けているのは、かれらの声だ。かれらはポーズをとったその瞬間から私たちを見つめ、かれらの老いた身体は大いなる沈黙を語っている。話して! と私はいいたくなる。佐賀純一は、いまどこにいるのだろう? かれらの物語を書き記すのは誰? どうやって言葉を召喚する? どんな言葉を呼び出す?声たち

もちろん浦島太郎の物語は「むかしむかし」ではじまるのだが、私の記憶がぶつかるのは次の一語だ。「あぶない!」これは、私が最初に覚えた日本語の単語のひとつだったのかもしれない。私の母は、自分がひどい心配にかられたり、私を危険から守る必要に迫られたとき、口をついて出てくる言葉がつい日本語ばかりになってしまうのはなぜかということを、どうにも説明することができなかった。私を危害から守るための命令を発するときの単語は、本能的に「あぶない」だったのだ。それを耳にするたび、私はそれが彼女と彼女の母親のあいだでも使われた、深い過去からやってきたものだということを感じていた。「いい子ね」。これが、いとこたちと私にとっての、テイおばあちゃんの言葉だ。この人は一言も英語を話さなかった。私たちはみんないい子で、老年にあっては誰からも賢い人だと見なされるようになったテイがそういうのであれば、それは本当だったにちがいない。この母方の祖母が小柄な女性だったことを、私は覚えている。子孫の全員が受け継ぐことになった尖った顎と不正咬合をもち、背骨は曲がり、薄くなった白髪を首筋で小さく結っていた。夏になると、私たちはサン・フランシスコの日本街、ポスト・ストリートにある天井の高い古いヴィクトリア朝風の家屋で、家族がやっている魚屋兼食料品店の二階に住んでいたテイを訪ねた。祖父、ついでおじやおばたちが、1900年代以来、このウオキ・フィッシュ・マーケットを経営していたのだ。ときには私はポスト・ストリートを見晴らす彼女の部屋の大きなダブルベッドで、テイのかたわらに眠ることがあった。

祖母はとてもか細く静かで、存在がほとんど感じられないくらいだった。彼女は毎朝、夜明けとともにベッドから起き出した。下のポスト・ストリートの夜は遠くから聞こえてくるジャズの音や人間のざわめきにみちていたが、早朝になるとそれがトラックから野菜や食料品を下ろす作業の音にかき消されていった。おじたちがあちらこちらと指示を叫びあい、かれらの足は音を立てながら長い階段を昇り降りして輸入された日本食品の箱を運ぶのだった ⸺ 鰹節、せんべい、海苔などを。私は腰の曲がったテイの後を追って古い家を歩き、長い階段を降り、祖父の厳めしい写真が飾られた仏壇での彼女の毎日のお参りをじっと観察し、鐘の音が長くたなびくのを追うように線香から立ちのぼる一すじの煙を見つめ、それからまた彼女の後について台所を抜け、裏階段を降りてフィッシュ・マーケットに裏口から入り、冷蔵庫の冷たい息と生魚の臭いを通り過ぎていった。私は彼女が砂糖付きコーンフレークスと、お茶漬けというものだと私も知っていた緑と黄色の包みに、手を伸ばすのを見た。

母はコーンフレークスにまぶされた多すぎる砂糖も、お茶漬けに含まれる塩分も許してくれなかったが、テイおばあちゃんはそんなことを考えもしなかった。私は朝ごはんと昼ごはんを、好きなように食べることができた。これこそ、自宅のすぐ下に自分ちの食料品店があることの贅沢だった。私が自分のお茶碗からお茶漬けを啜っているあいだ、テイは背中を丸めて大きな台所の端にすわり、節ばって皺だらけの両手を休みなく動かして、鉤針で毛布を編んでいた。

「みんな! 勝った!」私の父は勝負事となるといつも熱くなる人で、また実際強くもあった。本気で熱中し真剣になるため、遊びごとのひとつひとつの動きが特別な活気をおびるのだった。ある夏、キャンプをしながら、彼は私たちにポーカーを教えた。これはキリスト教の牧師としてはどうも正統的な活動とはいえなかったが、父が正統的であったためしはなかった。ともかく私たちは、河原で集めた小石を賭けて遊んだ。父はすごいブラッフをかまして私たちをからかうのが好きだった。すでに山となっている自分の小石をカードテーブルの中心に押しやりながら、父はすべてを賭けた。「みんな!」と彼が大声を出したので、夏を一緒に過ごしに来ていた彼の母親は、あきれたというように目玉をくるくる回した。私たち全員が怖じ気づいた蠅のように降りてしまうと、彼はぜんぜん良くない手をさらけだしてみせた。「勝った!」父はレッドウッドの森にむかって叫んだ。

父方の祖母であるトミは、自分でブロークン・イングリッシュと呼んでいる言葉をしゃべり、バークリーのサンパブロ・アヴェニューにある小さなアパートに一人で住んでいて、ときどき私たちのところを訪れては、しばらく滞在した。テイが「おばあちゃん」だったのに対して、ブロークン・イングリッシュのトミの方は、いつだって「グランマ」だった。

彼女の夫はニューヨークで修行した洋服の仕立て屋だった。オークランドにヨコハマ・テイラー・ショップという店を開き、祖母もそこで縫製を覚えたのにちがいない。彼女はいつも帽子と手袋を身につけて、お洒落をしていた ⸺ 優雅で、そして空しい。自分の体型や姿勢を自慢に思っていた。彼女は生涯のほとんどの期間、真ん中できつく締めるコルセットをつけていたのだ。朝、彼女の部屋に入っていって、紐がきつく締まるよう引っ張ってあげるのが、私は好きだった。トミに抱きつくと、胴のまわりに固いコルセットが感じられ、小さな鈎がときにはこっちの胸に食いこんでくるのもわかった。彼女は私が自分のいちばん上の娘である私の伯母に似てとてもかわいいといい、その伯母はというと、若いころのトミ自身に似ているのだった。彼女は私に、自分はいまも続く美しい女たちの血統の一部なのだということを思わせた。彼女のやることなすことにいつも興味をもっていた私は、彼女が万年筆を青インクでみたし、上から下へと漢字を書きつらねながら手紙を書き、染みがつかないように注意深く吸い取り紙を使うのを見ていた。

彼女は手紙の最後を、「神さまのおかげ」という言葉で締めくくっていたのかもしれない。おそらく東京で、キリスト教の宣教師たちの勧めで信者となった彼女には、おなじ教会に通う一世のともだちがたくさんいた。ときには私はソファでお祈りをする彼女の隣に腰かけたが、彼女はお祈りをしているうちにそのまま眠ってしまうのだった。すごい鼾をかく人で、夜には彼女の喉の吠え声が壁を突き抜けて聞こえた。

私が東京に留学し、漢字の練習をして彼女に日本語で手紙を出せるようになったその年に、彼女は死んだ。あるいはそのころにはもう、彼女は私のブロークン・ジャパニーズを読むにはあまりに衰弱していたのかもしれない。父がイリノイ州オークパークから手紙をくれた。祖母が亡くなるまで、彼とその姉妹が、そこで彼女の看病をしていたのだ。父の手紙によると、毎日、グランマは驚いたように目を覚まし、こういったそうだ。「まだ生きている?」

あぶない。いい子ね。みんな! 勝った! まだ生きている? 最初から最後まで、私にとって日本語以外の言語にすれば心を掴む感覚が失われてしまう、そんな言葉ばかり。そしてそれらの言葉の内に、声たちが帰ってくる ⸺ 母の挨拶のかん高い声、テイの低くて笑いを含んだ声、父のはじける喜び、トミの激しい威厳。二人の祖母はいずれも百年に十年足りない歳まで生きた。彼女たちの顔や手に、垂れた乳房に、曲がった背骨に、腫瘤のできた足に、刻みこまれているのは、歴史と経験の風景の全体だ。けれどもそうしたすべては、とてもすばやく起こった。1900年、二人がアメリカに到着したとき、やがてひとつの戦争が自分たちの人生をちょうど真ん中で中断させ、子供たちを散り散りにし、夢を破壊するのだということを、どうすれば知りえたというのか? なぜ二人やその他の女たちは、失敗した男たちの不満に苦しみ、大恐慌時代を耐えつつ家族を育て、子供たちが虜囚となったり戦場に死ににやられるのを見るために、こんなに遠くまでやってきたのだろう? 彼女たちの身体の入り組んだ風景、あの沈黙の地図、刻みこまれた人生を、誰が読むことができただろう? いい子ね。まだ生きている? 彼女たちの声は風景の上を漂い、廃虚につきまとい、さまざまな遺物のまわりで渦巻き、私たちの記憶と忘却の博物館に生命と物語を吹きこむ。

カメラ箱の中の未来

未来は、過去を欠いて、存在できるのだろうか? そう、それだって別にかまわないのでは? 時間が止めることのできない、ひたすら進んでゆく不可避の連続体だとしたら、たしかに未来とは、ただ起きるだけのものだ。けれどももし未来がまた、私たちが想像するものでもあるとすれば、そのとき過去と、その過去の記憶は、そんな未来を築いてゆくために、存在しなくてはならない。ある人は、ソナベンドのように、記憶とは幻想のもの、想像のものだというだろう。それはたしかにそうなのだ。記憶とは、過去の諸事件に関して私たちが語る一種の物語だともいえる。そのある部分は、私たちが想像したものだ。私たちは精一杯よく覚えようとするものの、本当のことをいえば、真実は必ずしもおもしろい話にならない。それにどのような物語をも超えて空中をさまよっている記憶、説明不能な記憶がある。醤油のしょっぱい匂い、私のおでこに当てられた父の手の肌ざわりと重み、海藻の多い海を照らし出す光のかたちと踊り、あちこちに孔のあいた砂と砕け崩れる貝殻の浜辺にきらめきつつ消えてゆく、輝く波の音。海岸にたたずむのは、年老いた浦島太郎。彼はカメラ箱を通して見るのだろうか、それともカメラ箱が彼に焦点を合わせているのだろうか? あるいはいずれにせよ彼は、じつはその箱におさめられた一掴みの灰でしかないのか? すべてはとてもすばやく起こった ⸺ ありえない夢のように。しかし新正の撮った自然および人間の風景がここにあって、それは本当に起こったのだということを、あなたに教えてくれる。飛ぶように逃げ去ってゆく証拠だが、証拠であることに変わりはない。それは未来の自由のために力を与えてくれる、滅びからの大きな贈り物だ。

カレン・テイ・ヤマシタ/2000年6月

管 啓次郎・訳