THE SILENT LAND / Prison Camps in Siberia

Jun Henmi

In the outer sea of Sado, there is a cape from where you can see Siberia. There is a place on this cape called “Sainokawara”, where several stone towers and various sizes of Jizo statues are lined up. Local people believe that they can meet the dead when they come to this riverbank.

About twenty years ago, I met an old woman at Sainokawara. The old woman’s son had been detained in Siberia and had passed away.

“When I heard that my brother died in Siberia, I came to this riverbank. By offering flowers to Jizo-sama like this and stacking stones, I feel like I can meet my brother.”

The voice of the old woman still overlaps with the harsh winter sea roar of the outer sea. My uncle’s husband, who lives in my hometown of Toyama, was also taken to Siberia and passed away there. My aunt, who is now eighty years old, says,

“I want to go to Siberia where my father died, but I still can’t. I want to go there once before the day of my departure comes.”

She repeats it over and over again. Tears start flowing as she speaks. When she received the news of her husband’s death, she pounded the floor with a mix of regret and sadness, rolled around, and cried. However, as she raised and cared for the three young children her husband left behind, she stopped crying. It’s only recently that tears come whenever she remembers her husband. She wonders if there was still a place for tears to come out.

In the defeat of August 15, 1945, it is said that over six hundred thousand Japanese people were detained in Siberia from former Manchuria, North Korea, and Karafuto. Of those, more than sixty thousand people, over ten percent, died in hunger and hard labor with homesickness in their hearts. They were buried by digging holes at the base of birch trees, so they were also called “birch nourishment”, and not even their names or dates of death were recorded.

Among these deceased is Hatao Yamamoto from Oki. He was drafted as a private second class in the summer of 1944 and left for the front leaving four children behind in Shin’ei. He was accused of “conspiracy espionage against the Soviet Union” under Article 58, Section 6 of Soviet domestic law, for his previous work in the South Manchuria Railway Investigation Department and his time at the Harbin Special Agency six months before the defeat, and was sentenced to twenty-five years in prison for spying. The arbitrariness of the Soviet Union judging Japanese people by its own laws is now rightly criticized. Moreover, even women who worked as telephone operators in Shin’ei’s telephone exchange and at the Soviet consulate in Dairen were taken into custody. A woman who taught Japanese at the consulate was detained in the Soviet Union until 1955.

In August 1948, Katsuo Yamamoto died of illness in a camp in Khabarovsk, but his comrades secretly wrote down the date and name of his death on a birch tree. Birch trees were the grave markers for the deceased.

Yamamoto traveled around various places, including Sverdlovsk, but held gatherings and poetry meetings in the camps. During the days of despair when he didn’t know when he could return home, he always told his comrades, “We will definitely return home together. Until that day, I want to remember beautiful Japanese language.” Starting the “Amur Poetry Society” in the Khabarovsk camp was one of those efforts.

“What Mr. Yamamoto taught us was not just haiku. No matter what adversity we face, what’s important is how to live as honest human beings,” said a comrade.

In December 1948, Gunshiro Hayashi returned as one of the last long-term detainees from the Soviet zone, along with 1,025 others. He copied Yamamoto’s haiku, tanka, and poetry onto wrapping paper, hid them in the seams of his pants, and delivered them to the bereaved families.

He also said that people are either “on that side” or “on this side,” and which side one belongs to is merely a matter of chance. “That side” would be the world of the deceased. As someone who survived on “this side,” it was said that one had no choice but to live for the sake of the dead, at least.

I think of myself as a child when I see small icicles hanging from the eaves.

– Hatao

In Siberia, temperatures drop below minus thirty degrees in winter, and icicles become as sharp as blades. Perhaps he found small icicles and named each one after his four children whom he brought back to Japan. Until just before his death, he continued to write about how to live as a Japanese in a thin Soviet notebook. Of course, the notebook was confiscated by the Soviet authorities. If what he wrote was found, he would be sent to solitary confinement or face heavier penalties. As I learn about Yamamoto’s way of life, I can’t help but think that living well is also a way of dying well.

In his will, Yamamoto wrote:

“It is the Japanese nation that can, in the future, serve as the only mediator to integrate the cultures of the East and the West, and contribute to the reconstruction of world culture with the superior moral culture of the East — humanitarianism. We must never forget this historical mission even for a moment.”

The path of “reconstruction of world culture” that he prayed for while thinking of Japan and his family in Siberia is far removed from the reality of our country today. His question still seems heavy.

His will was delivered to his family by his fellow inmates through an unimaginable means called “memory.”

Memory is the traditional method of transmitting Japanese culture. However, what is remembered through body and mind and passed on to the next generation can become a great power of culture.

The photo book “Silent Land” by ARAMASA Taku seems to tell through the camera that memory is culture.

ARAMASA experienced the defeat of 1945 in Jiamusi, former Manchuria. He was nine years old at the time. Two years after the defeat, he arrived at his grandfather’s house in Sakata City, Yamagata Prefecture, from the continent. It may have been the impulse to look back at himself, who might have become a “left-behind orphan,” that prompted ARAMASA to dig up memories of his childhood in former Manchuria. One day, there was an incident where the young men in the neighborhood who had been fond of him suddenly disappeared from the town with the invasion of the Soviet army. Later, he learned that those young men had been detained in Siberia.

The year the book was published, 1995, marked half a century since the defeat. However, shouldn’t we bear in mind that it is not “already half a century” but “still half a century”? We must not forget that our country is built on the foundation of countless deceased who died on the battlefield or in the frozen soil of Siberia. Today, when memories of wartime experiences are being lost over time, the significance of digging up another journey to find the disappeared Japanese through the lens of one photographer is profound and immense. It is because we feel that it is important to quietly listen to the voices of the land and the deceased that come through that journey. / GPT-4

Jun Henmi, Author

About twenty years ago, I met an old woman at Sainokawara. The old woman’s son had been detained in Siberia and had passed away.

“When I heard that my brother died in Siberia, I came to this riverbank. By offering flowers to Jizo-sama like this and stacking stones, I feel like I can meet my brother.”

The voice of the old woman still overlaps with the harsh winter sea roar of the outer sea. My uncle’s husband, who lives in my hometown of Toyama, was also taken to Siberia and passed away there. My aunt, who is now eighty years old, says,

“I want to go to Siberia where my father died, but I still can’t. I want to go there once before the day of my departure comes.”

She repeats it over and over again. Tears start flowing as she speaks. When she received the news of her husband’s death, she pounded the floor with a mix of regret and sadness, rolled around, and cried. However, as she raised and cared for the three young children her husband left behind, she stopped crying. It’s only recently that tears come whenever she remembers her husband. She wonders if there was still a place for tears to come out.

In the defeat of August 15, 1945, it is said that over six hundred thousand Japanese people were detained in Siberia from former Manchuria, North Korea, and Karafuto. Of those, more than sixty thousand people, over ten percent, died in hunger and hard labor with homesickness in their hearts. They were buried by digging holes at the base of birch trees, so they were also called “birch nourishment”, and not even their names or dates of death were recorded.

Among these deceased is Hatao Yamamoto from Oki. He was drafted as a private second class in the summer of 1944 and left for the front leaving four children behind in Shin’ei. He was accused of “conspiracy espionage against the Soviet Union” under Article 58, Section 6 of Soviet domestic law, for his previous work in the South Manchuria Railway Investigation Department and his time at the Harbin Special Agency six months before the defeat, and was sentenced to twenty-five years in prison for spying. The arbitrariness of the Soviet Union judging Japanese people by its own laws is now rightly criticized. Moreover, even women who worked as telephone operators in Shin’ei’s telephone exchange and at the Soviet consulate in Dairen were taken into custody. A woman who taught Japanese at the consulate was detained in the Soviet Union until 1955.

In August 1948, Katsuo Yamamoto died of illness in a camp in Khabarovsk, but his comrades secretly wrote down the date and name of his death on a birch tree. Birch trees were the grave markers for the deceased.

Yamamoto traveled around various places, including Sverdlovsk, but held gatherings and poetry meetings in the camps. During the days of despair when he didn’t know when he could return home, he always told his comrades, “We will definitely return home together. Until that day, I want to remember beautiful Japanese language.” Starting the “Amur Poetry Society” in the Khabarovsk camp was one of those efforts.

“What Mr. Yamamoto taught us was not just haiku. No matter what adversity we face, what’s important is how to live as honest human beings,” said a comrade.

In December 1948, Gunshiro Hayashi returned as one of the last long-term detainees from the Soviet zone, along with 1,025 others. He copied Yamamoto’s haiku, tanka, and poetry onto wrapping paper, hid them in the seams of his pants, and delivered them to the bereaved families.

He also said that people are either “on that side” or “on this side,” and which side one belongs to is merely a matter of chance. “That side” would be the world of the deceased. As someone who survived on “this side,” it was said that one had no choice but to live for the sake of the dead, at least.

I think of myself as a child when I see small icicles hanging from the eaves.

– Hatao

In Siberia, temperatures drop below minus thirty degrees in winter, and icicles become as sharp as blades. Perhaps he found small icicles and named each one after his four children whom he brought back to Japan. Until just before his death, he continued to write about how to live as a Japanese in a thin Soviet notebook. Of course, the notebook was confiscated by the Soviet authorities. If what he wrote was found, he would be sent to solitary confinement or face heavier penalties. As I learn about Yamamoto’s way of life, I can’t help but think that living well is also a way of dying well.

In his will, Yamamoto wrote:

“It is the Japanese nation that can, in the future, serve as the only mediator to integrate the cultures of the East and the West, and contribute to the reconstruction of world culture with the superior moral culture of the East — humanitarianism. We must never forget this historical mission even for a moment.”

The path of “reconstruction of world culture” that he prayed for while thinking of Japan and his family in Siberia is far removed from the reality of our country today. His question still seems heavy.

His will was delivered to his family by his fellow inmates through an unimaginable means called “memory.”

Memory is the traditional method of transmitting Japanese culture. However, what is remembered through body and mind and passed on to the next generation can become a great power of culture.

The photo book “Silent Land” by ARAMASA Taku seems to tell through the camera that memory is culture.

ARAMASA experienced the defeat of 1945 in Jiamusi, former Manchuria. He was nine years old at the time. Two years after the defeat, he arrived at his grandfather’s house in Sakata City, Yamagata Prefecture, from the continent. It may have been the impulse to look back at himself, who might have become a “left-behind orphan,” that prompted ARAMASA to dig up memories of his childhood in former Manchuria. One day, there was an incident where the young men in the neighborhood who had been fond of him suddenly disappeared from the town with the invasion of the Soviet army. Later, he learned that those young men had been detained in Siberia.

The year the book was published, 1995, marked half a century since the defeat. However, shouldn’t we bear in mind that it is not “already half a century” but “still half a century”? We must not forget that our country is built on the foundation of countless deceased who died on the battlefield or in the frozen soil of Siberia. Today, when memories of wartime experiences are being lost over time, the significance of digging up another journey to find the disappeared Japanese through the lens of one photographer is profound and immense. It is because we feel that it is important to quietly listen to the voices of the land and the deceased that come through that journey. / GPT-4

Jun Henmi, Author

辺見じゅん

佐渡の外海府に、シベリアが見えるという岬がある。

この岬に「賽の河原」と呼ばれるところがあり、いくつもの石積みの塔と、大小の地蔵が列をつくっている。土地の人たちはこの河原に来ると死者に会えるという。

二十年程前、私は賽の河原で一人の老女に会った。老女の息子はシベリアに抑留され、亡くなっていた。

「おら、兄(あん)ちゃんがシベリアで死んだと聞いたときもこの河原へ来たちゃ。こうやって地蔵さまに花こをあげ、石積んでると兄ちゃんに会える気がするのだちゃのォ」

老女の声が、今も外海府の冬の厳しい海鳴りと重なって思い出されてくる。私の故郷富山に住む叔母の夫もシベリアに連れて行かれ、その地で亡くなった。八十歳になる叔母は、

「父ちゃんな死んだシベリアに行きたいがやけど、わしな、まだ行けんちゃ。お迎えの日が来るまでいっぺん行きたいがや」

何度も繰り返すように語っている。語っているうちに涙があふれてくる。夫の死亡の知らせが届いたときは、口惜しいやら悲しいやらで床を叩き、ころげ廻って泣いた。しかし夫の残した三人の幼い子等を育てているうち涙も出なくなった。それが最近になって夫を思い出すたび涙が出てくる。まだ涙の出る場所が残っていたのかと思うそうだ。

昭和二十年八月十五日の敗戦で、旧満州、北朝鮮、樺太から極寒のシベリアに抑留された日本人は六十万人以上といわれている。そのうちの一割を超える六万人以上の人々が、望郷の思いを抱いたまま飢えと重労働の中で死んでいった。死者は白樺の木の根元に穴を掘って埋められたので「白樺のこやし」ともいわれ、死亡年月日はおろか氏名も記されなかった。

そうした死者たちの一人に、隠岐出身の山本幡男氏がいる。彼は昭和十九年夏に二等兵として召集され、四人の子等を新京に残して出征した。満鉄調査部にいたこと、敗戦の半年前にハルビン特務機関にいたことがソ連の国内法第五十八条第六項の「ソ連に対する謀略諜報行為」に当たるとされ、スパイ罪で二十五年の刑を受けたのだ。ソ連が自国の法律によって日本人を裁いた理不尽さは今日、指摘される通りである。しかも、シベリアには新京の電話交換手や大連のソ連領事館に勤めていた女性たちまで連行された。領事館で館員たちに日本語を教えていた女性は、昭和三十年までソ連に抑留されていたのである。

昭和二十九年の八月、山本勝男氏はハバロフスクの収容所で病死したが、仲間たちが白樺の木に秘かに死亡した日と名前を書いておいた。白樺は死者たちの墓標だった。

山本氏はスベルロフスクをはじめ転々としたが、収容所内で万葉集の会や句会を開いた。いつ帰国出来るかわからず、絶望的な気持に陥っていた日々、仲間たちに、「ぼくたちは必ずみんなで帰国しよう。その日まで美しい日本語を忘れないようにしたい」と常に語った。ハバロフスクの収容所で「アムール句会」を始めたのもその一つであった。

「山本さんが私たちに教えてくれたのは俳句だけではなかった。どんな逆境にいても大切なのは人間として誠実にいかに生きるかということでした」

昭和三十一年暮、ソ連地区からの最後の長期抑留者一千二十五名の一人として帰還した林軍四郎氏は、山本氏の俳句や短歌や詩を薬包紙に小さな字で写し、ズボンの縫目に隠して持ち帰り、遺族に届けている。

その人はまた、人間は「あちら側」か「こちら側」か、二つのうちのどちらかにいる。どちらの側に属するかはほんの僅かな偶然でしかないと訥弁で語っていた。「あちら側」とは、死んでいった者たちの世界であろう。「こちら側」に偶然生き残った者として、せめて死者のためにも一生懸命に生きていくことしかないとも言われた。

小さきをば子供と思ふ軒氷柱 幡男

シベリアでは冬になると氷点下三十度を超え、氷柱も鋭利な刃もののようになる。小さな氷柱を見つけ、その一つ一つに日本へ引き揚げた四人の子等の名をつけて呼んでいたのだろう。亡くなる寸前までソ連製の薄いザラ紙のノートに日本人としてどう生きるかを書き続けていた。むろんそのノートはソ連側に没収された。書いたものが見つかれば営倉送りや刑が加重される。山本氏の生き方を知るにつれ、よりよく生きることはまた、よく死ぬことではないかと思われてならない。

山本氏の遺書の中に、次のような言葉がある。

「日本民族こそは将来、東洋、西洋の文化を融合する唯一の媒介者、東洋のすぐれた道義の文化 ⸺ 人道主義を以て世界文化再建に寄与し得る唯一の民族である。この歴史的使命を片時も忘れてはならぬ」

シベリアの地で遙かに日本や家族を想いつつ祈願した「世界文化再建」の道は、今日の私たちの国の実状とはあまりにも隔たっている。彼の問いかけた命題はいまなお重いものに思える。

この遺書は、収容所の仲間たちにより「記憶」という想像を絶した手段によって遺族に届けられた。

記憶は、日本古来の文化の伝達法である。しかしまた、肉体や精神を通して記憶されたものが次代に引き継がれてこそ文化の大いなる力ともなりうるのだ。

このたびの新正卓氏の写真集『沈黙の大地』は、カメラを通してまさに記憶が文化であることを物語っているように思えた。

一九四五年の敗戦を新正氏が迎えたのは、旧満州の佳木斯(チャムス)であった。九歳のときだったという。敗戦後二年を経て大陸から山形県酒田市の祖父の実家に辿りついた。その新正氏が「残留孤児」になっていたかもしれぬ自らを顧みる衝動に突き動かされて幼年期の旧満州での記憶を掘り起こしていったことが、この写真集を上梓した要因であったろう。その一つに、可愛がってくれた近所の青年たちが或る日、ソ連軍の侵攻と共に町から忽然と姿を消してしまう出来事があった。後にその青年たちがシベリアへ抑留されたことを知った。

本書が出版された一九九五年は、敗戦から半世紀を迎える年である。だが、「もう半世紀」ではなく、「まだ半世紀」でしかないことを私たちは肝に銘じるべきではないだろうか。私たちの国が、戦場に或いはシベリアの凍土に死んでいった無数の死者たちを土台に成り立っていることを忘却してはならない。戦争体験の「記憶」が歳月と共に失われつつある今日こそ、一人の写真家が消えてしまった日本人を捜し出すもう一つの旅を掘り起こした意義は深く大きい。その旅を通して聴こえてくる大地や死者たちの声に、私たちは静かに耳を傾け、真向うことが大切に思えてくるからである。

この岬に「賽の河原」と呼ばれるところがあり、いくつもの石積みの塔と、大小の地蔵が列をつくっている。土地の人たちはこの河原に来ると死者に会えるという。

二十年程前、私は賽の河原で一人の老女に会った。老女の息子はシベリアに抑留され、亡くなっていた。

「おら、兄(あん)ちゃんがシベリアで死んだと聞いたときもこの河原へ来たちゃ。こうやって地蔵さまに花こをあげ、石積んでると兄ちゃんに会える気がするのだちゃのォ」

老女の声が、今も外海府の冬の厳しい海鳴りと重なって思い出されてくる。私の故郷富山に住む叔母の夫もシベリアに連れて行かれ、その地で亡くなった。八十歳になる叔母は、

「父ちゃんな死んだシベリアに行きたいがやけど、わしな、まだ行けんちゃ。お迎えの日が来るまでいっぺん行きたいがや」

何度も繰り返すように語っている。語っているうちに涙があふれてくる。夫の死亡の知らせが届いたときは、口惜しいやら悲しいやらで床を叩き、ころげ廻って泣いた。しかし夫の残した三人の幼い子等を育てているうち涙も出なくなった。それが最近になって夫を思い出すたび涙が出てくる。まだ涙の出る場所が残っていたのかと思うそうだ。

昭和二十年八月十五日の敗戦で、旧満州、北朝鮮、樺太から極寒のシベリアに抑留された日本人は六十万人以上といわれている。そのうちの一割を超える六万人以上の人々が、望郷の思いを抱いたまま飢えと重労働の中で死んでいった。死者は白樺の木の根元に穴を掘って埋められたので「白樺のこやし」ともいわれ、死亡年月日はおろか氏名も記されなかった。

そうした死者たちの一人に、隠岐出身の山本幡男氏がいる。彼は昭和十九年夏に二等兵として召集され、四人の子等を新京に残して出征した。満鉄調査部にいたこと、敗戦の半年前にハルビン特務機関にいたことがソ連の国内法第五十八条第六項の「ソ連に対する謀略諜報行為」に当たるとされ、スパイ罪で二十五年の刑を受けたのだ。ソ連が自国の法律によって日本人を裁いた理不尽さは今日、指摘される通りである。しかも、シベリアには新京の電話交換手や大連のソ連領事館に勤めていた女性たちまで連行された。領事館で館員たちに日本語を教えていた女性は、昭和三十年までソ連に抑留されていたのである。

昭和二十九年の八月、山本勝男氏はハバロフスクの収容所で病死したが、仲間たちが白樺の木に秘かに死亡した日と名前を書いておいた。白樺は死者たちの墓標だった。

山本氏はスベルロフスクをはじめ転々としたが、収容所内で万葉集の会や句会を開いた。いつ帰国出来るかわからず、絶望的な気持に陥っていた日々、仲間たちに、「ぼくたちは必ずみんなで帰国しよう。その日まで美しい日本語を忘れないようにしたい」と常に語った。ハバロフスクの収容所で「アムール句会」を始めたのもその一つであった。

「山本さんが私たちに教えてくれたのは俳句だけではなかった。どんな逆境にいても大切なのは人間として誠実にいかに生きるかということでした」

昭和三十一年暮、ソ連地区からの最後の長期抑留者一千二十五名の一人として帰還した林軍四郎氏は、山本氏の俳句や短歌や詩を薬包紙に小さな字で写し、ズボンの縫目に隠して持ち帰り、遺族に届けている。

その人はまた、人間は「あちら側」か「こちら側」か、二つのうちのどちらかにいる。どちらの側に属するかはほんの僅かな偶然でしかないと訥弁で語っていた。「あちら側」とは、死んでいった者たちの世界であろう。「こちら側」に偶然生き残った者として、せめて死者のためにも一生懸命に生きていくことしかないとも言われた。

小さきをば子供と思ふ軒氷柱 幡男

シベリアでは冬になると氷点下三十度を超え、氷柱も鋭利な刃もののようになる。小さな氷柱を見つけ、その一つ一つに日本へ引き揚げた四人の子等の名をつけて呼んでいたのだろう。亡くなる寸前までソ連製の薄いザラ紙のノートに日本人としてどう生きるかを書き続けていた。むろんそのノートはソ連側に没収された。書いたものが見つかれば営倉送りや刑が加重される。山本氏の生き方を知るにつれ、よりよく生きることはまた、よく死ぬことではないかと思われてならない。

山本氏の遺書の中に、次のような言葉がある。

「日本民族こそは将来、東洋、西洋の文化を融合する唯一の媒介者、東洋のすぐれた道義の文化 ⸺ 人道主義を以て世界文化再建に寄与し得る唯一の民族である。この歴史的使命を片時も忘れてはならぬ」

シベリアの地で遙かに日本や家族を想いつつ祈願した「世界文化再建」の道は、今日の私たちの国の実状とはあまりにも隔たっている。彼の問いかけた命題はいまなお重いものに思える。

この遺書は、収容所の仲間たちにより「記憶」という想像を絶した手段によって遺族に届けられた。

記憶は、日本古来の文化の伝達法である。しかしまた、肉体や精神を通して記憶されたものが次代に引き継がれてこそ文化の大いなる力ともなりうるのだ。

このたびの新正卓氏の写真集『沈黙の大地』は、カメラを通してまさに記憶が文化であることを物語っているように思えた。

一九四五年の敗戦を新正氏が迎えたのは、旧満州の佳木斯(チャムス)であった。九歳のときだったという。敗戦後二年を経て大陸から山形県酒田市の祖父の実家に辿りついた。その新正氏が「残留孤児」になっていたかもしれぬ自らを顧みる衝動に突き動かされて幼年期の旧満州での記憶を掘り起こしていったことが、この写真集を上梓した要因であったろう。その一つに、可愛がってくれた近所の青年たちが或る日、ソ連軍の侵攻と共に町から忽然と姿を消してしまう出来事があった。後にその青年たちがシベリアへ抑留されたことを知った。

本書が出版された一九九五年は、敗戦から半世紀を迎える年である。だが、「もう半世紀」ではなく、「まだ半世紀」でしかないことを私たちは肝に銘じるべきではないだろうか。私たちの国が、戦場に或いはシベリアの凍土に死んでいった無数の死者たちを土台に成り立っていることを忘却してはならない。戦争体験の「記憶」が歳月と共に失われつつある今日こそ、一人の写真家が消えてしまった日本人を捜し出すもう一つの旅を掘り起こした意義は深く大きい。その旅を通して聴こえてくる大地や死者たちの声に、私たちは静かに耳を傾け、真向うことが大切に思えてくるからである。

(へんみ じゅん 作家)

-

- Central Siberia Region. Kemerovo Oblast, Anzherskaya No-915, Water bottle of Japanese POW, 1995

-

- Transbaikal Region. Chita Oblast, Holbon Japanese POW Camp Dedicated Cemetery, 1995

-

- Transbaikal Region. Irkutsk Oblast, Tareya 212km, Japanese POW Camp Site, 1994

-

- Transbaikal Region. Irkutsk Oblast, Sosnovka Japanese POW Camp Site, 1995

-

- Transbaikal Region. Irkutsk Oblast, Sosnovka Japanese POW Camp Site, Abandoned Well, 1995

-

- Transbaikal Region. Irkutsk Oblast, Taraja 212km point, former site of Japanese prisoner of war camp, 1994

-

- Transbaikal Region. Irkutsk Oblast, Tayshet City “Ozellag” Prison Main Building Ruins, 1994

-

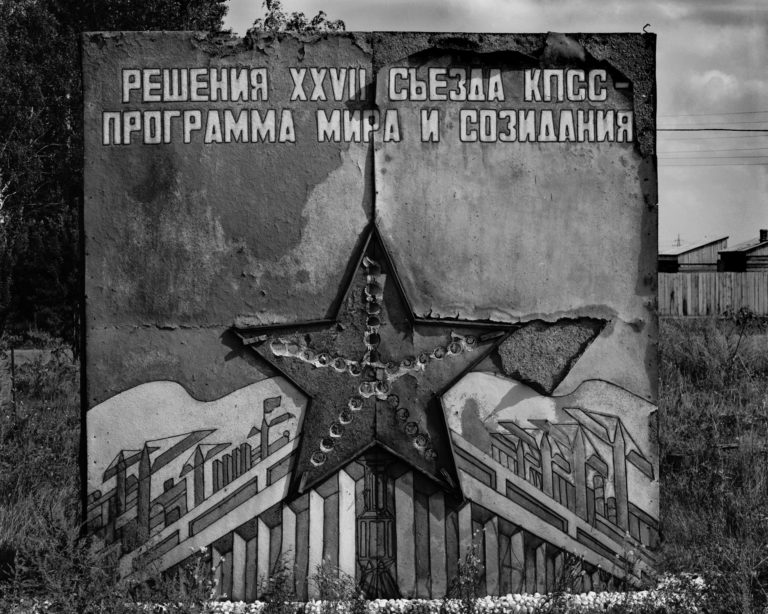

- Transbaikal Region. Irkutsk Oblast, Tayshet City “Ozellag” Prison, 27th Soviet Communist Party slogan, 1994

-

- Far Eastern Federal District. Khabarovsk, Credor station engine warehouse abandoned house (Discarded during construction), 1994

-

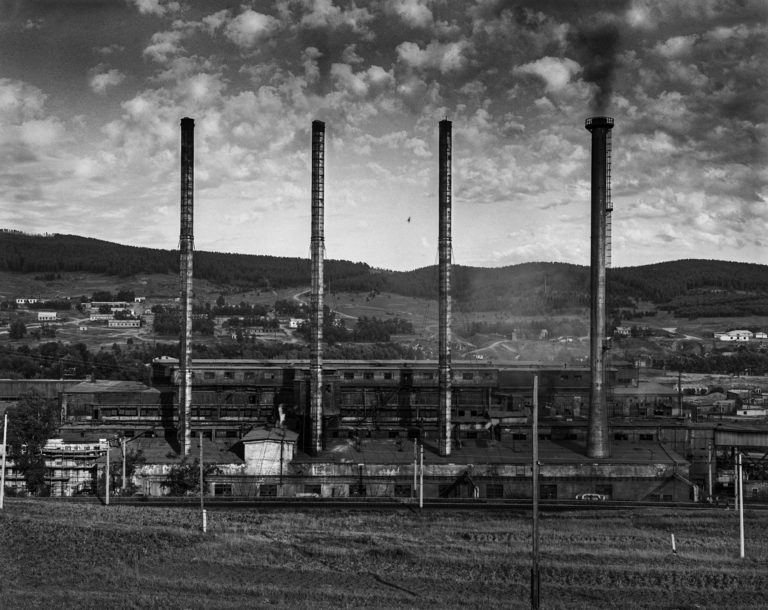

- Transbaikal Region. Chita Oblast, Peterovsky Iron Factory (Several Japanese POW camps on the far left), 1994

-

- Transbaikal Region. Chita Oblast, Common Cemetery in Tarbagatai Village (Cemetery of Japanese POWs in one stroke), 1994

-

- Transbaikal Region. Irkutsk Oblast, Orderly and beautiful “Marat” Japanese POW graveyard, 1994

-

- Transbaikal Region. Irkutsk Oblast, Vikhorevka No-24 outside the prison hospital fence, 1994

-

- Transbaikal Region. Irkutsk Oblast, Usolye-Sibirskoye Lageri No-12 Japanese POW Camp, 1994

-

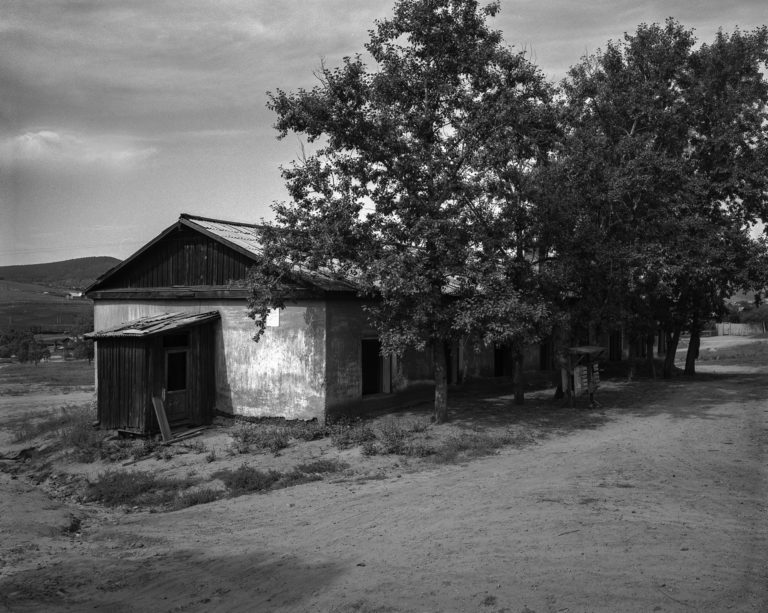

- Zabaikal Region, Irkutsk Oblast, Tuna No-203 Japanese POW Camp Prisoner’s Building, 1994

-

- Central Siberia, Kemerovo Oblast, Girls living in the Japanese POW camp in Angelosugensk, 1994

-

- Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita Oblast, Novopabrovka Japanese POW Containment Building, 1994

-

- Zabaykalsky Krai, Irkutsk Oblast, Vikhorevka Power Station Gymnasium (Construction of Japanese POWs), 1994

-

- Central Asia, Turkmenistan, Turkmenbashi, 2-story apartment (Japanese POW building), 1995

-

- Zabaykalsky Territory, Irkutsk Oblast, Tayshet City, Ozellag Prison Site, Soviet Communist Party Slogan, 1994

-

- Central Siberia, Krasnoyarsk Province, Chernogorsk Town Japanese POW Cemetery Cemetery Guard, Matsuo Bando (70) and his wife

-

- Boys playing at the site of the Japanese POW camp cemetery in Kiserobsk, Central Siberia, Kemerovo Oblast, 1995

-

- Central Asia Region, Republic of Uzbekistan, Angren Socialist Town Airaguma Mine (Construction of Japanese POWs), 1995

-

- Central Asia Region, Republic of Uzbekistan, Angren Socialist Town Airaguma Mine (Construction of Japanese POWs), 1995

-

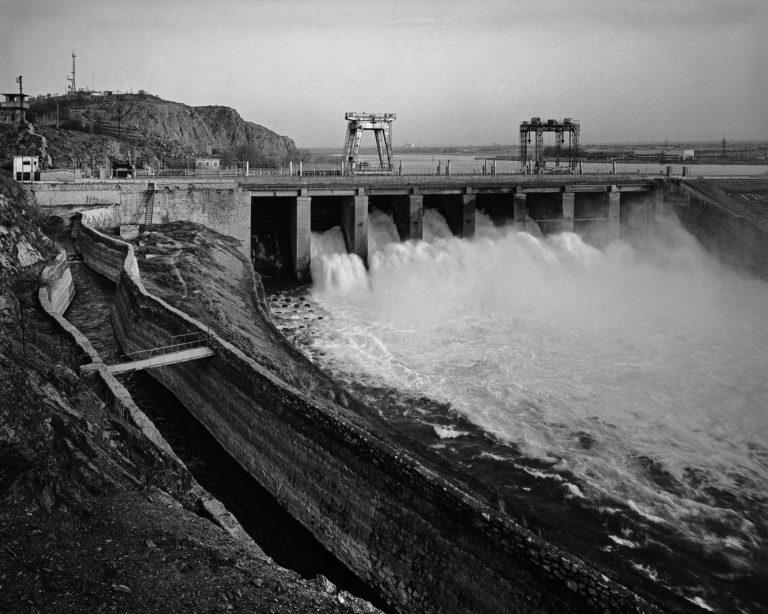

- Central Asia Region, Republic of Uzbekistan, Syr Darya Dam, Becoboard City (Construction of Japanese POWs), 1995

-

- Central Asia, Uzbekistan, Yanguri County, North Tashkent Canal and Bridge Ruins (Construction of Japanese POWs), 1995

-

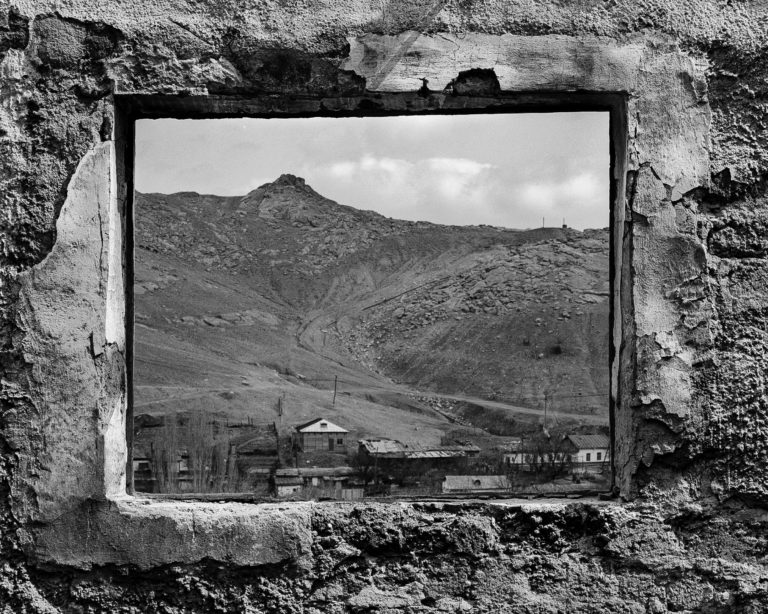

- Central Asia, Republic of Kazakhstan, Achisay Town, Zinc Mine Abandoned House Ruins (Construction of Japanese POWs), 1995

-

- Central Asia, Republic of Kazakhstan, Achisay Town, Turkestan County, Zinc Mine Wagon Nyetka (Construction of Japanese POWs), 1995

-

- Remnants of an abandoned sugar factory in Uchis Abakan, Central Siberia, Republic of Hakasiya (construction of Japanese POWs), 1995

-

- Remains of a sugar factory under construction in Uchis Abakan, Central Siberia, Republic of Hakasiya, Background Enisei River, 1995

-

- Abandoned sugar factory in Central Siberia, Republic of Hakasiya, Uchis Abakan, 2nd floor, North Side (Japanese POWs), 1995

-

- Abandoned in Uchisu Abakan, Japanese character graffiti on the site of a sugar factory “Quota achieved Damoy is near”, 1995

-

- Central Asia, Republic of Kazakhstan, Torquestanski County. 41 Jangiljina Street, Achisai Town, 1995

-

- Central Asia, Republic of Kazakhstan, Torquestanski County. 41 Jangiljina Dori, Achisai Town, Japanese POW Containment Facility, 1995

-

- Central Siberia, Kemerovo Oblast, Angelos Kaya No-915 Coal Mine Separation Processing Plant (Construction of Japanese POWs), 1995

-

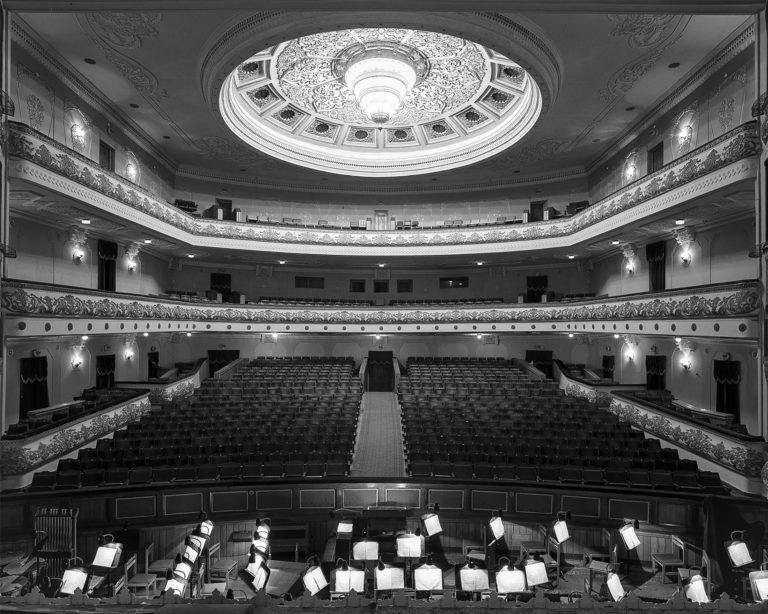

- Central Siberia, Kemerovo Oblast. Kiselobosk Coal Mine Club’s Innocence (Construction of Japanese POWs), 1995

-

- Central Siberia, Kemerovo Oblast. 36 Dzerzhinsky, Kiserobosk City (Lageri No-525, Ogerlenje No-12) Japanese POW Camp, 1995

-

- Approximately 150 soldiers are accommodated in the Zabaykalsky Japanese POW camp, Petrovsk, Chita Oblast, Zabaykalsky Krai, 1994

-

- “Theatre Navoy” in Tashkent, Central Asia, Uzbekistan, was successfully completed by selecting a professional group from Japanese POWs, 1995

-

- “Theatre Navoy, VIP Room” in Central Asia, Republic of Uzbekistan, Tashkent is a symbol of Uzbekistan’s independence, 1995

-

- Central Asia, Uzbekistan. 6th Tashkent City, Sarakrisky Street, Junction, Japanese POW Camp, 1995

-

- Central Asia, Uzbekistan. Tashkent Japanese POW camp, local residents call this street “Yaponsky, Lageri”, 1995

-

- Central Siberia, Kemerovo Oblast, Kemerovo Japanese POW. Lageri No-503 Oggerene No-2 Former Soviet Official Residence, 1995

-

- Central Asia, Uzbekistan, Tashkent, 16 Navoy Boulevard, Ethnic Restaurant “Uzbek” (built by Japanese POWs), 1995