Who am I / 私は誰ですか

-

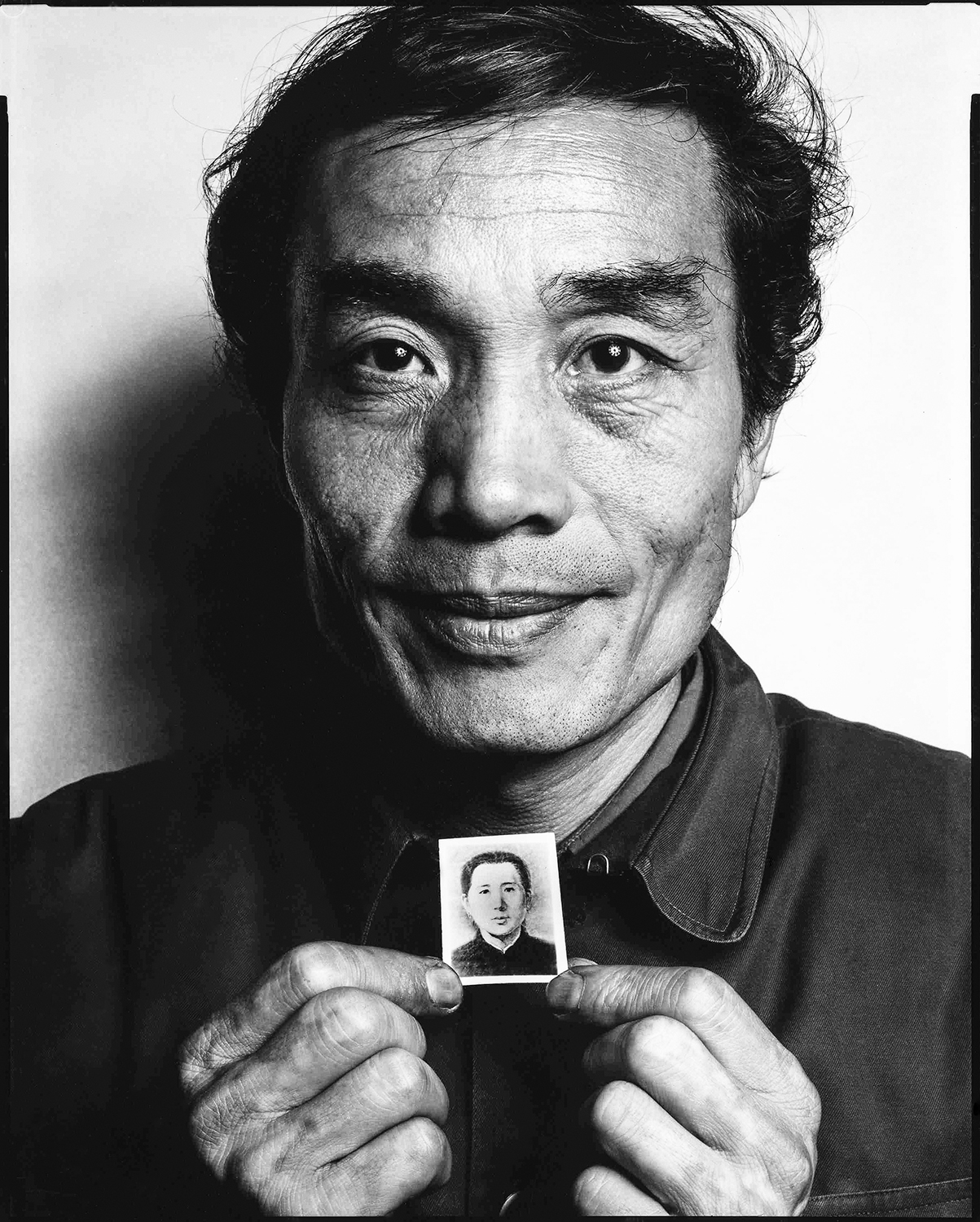

- 李 鵬/山東省/第7次訪日(昭和60年2月)P-1215

-

- 高 雅麗/奉天省/第7次訪日(昭和60年2月)P-448

-

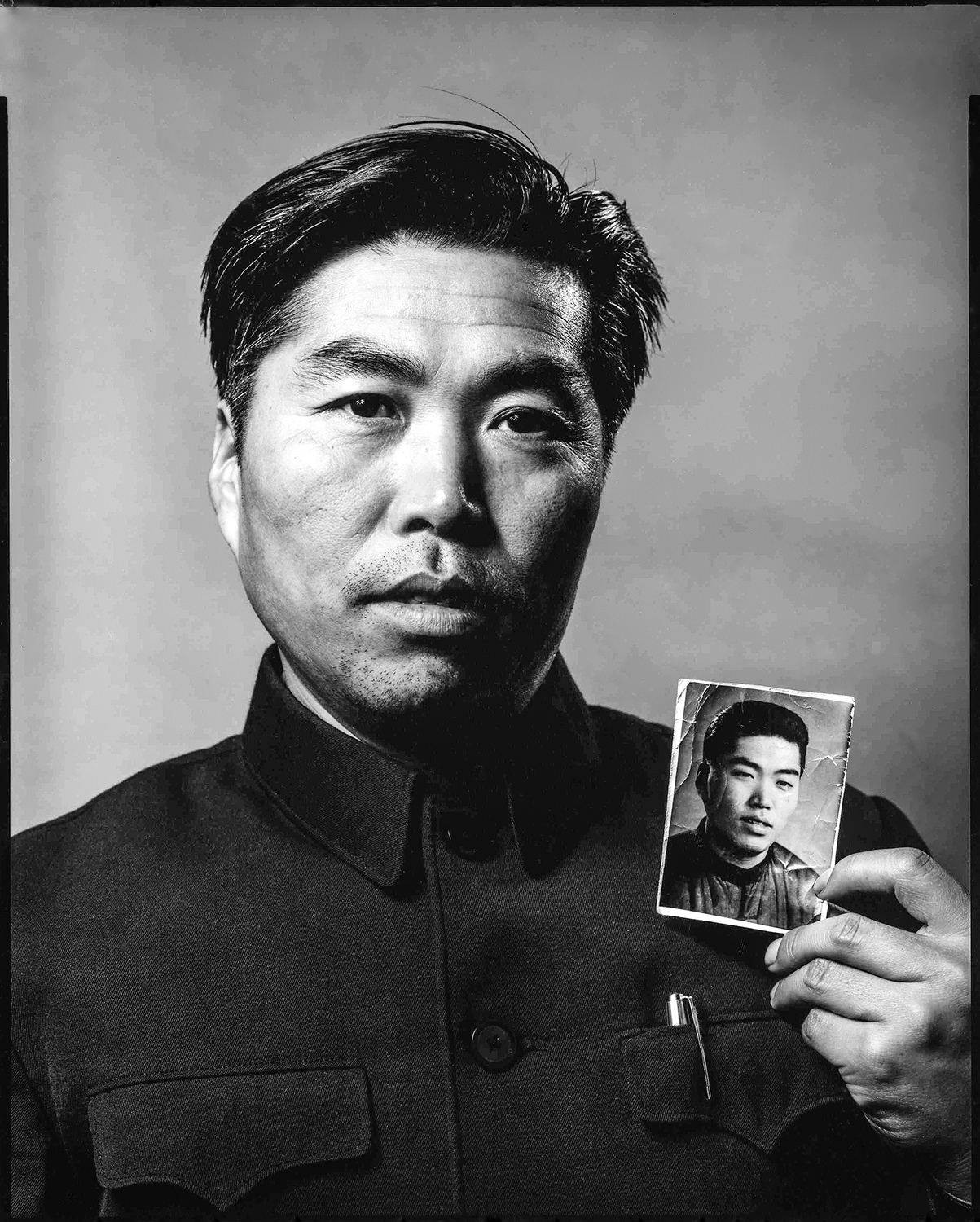

- 高 世復/奉天省/第2次訪日(昭和57年2月)P-1071

-

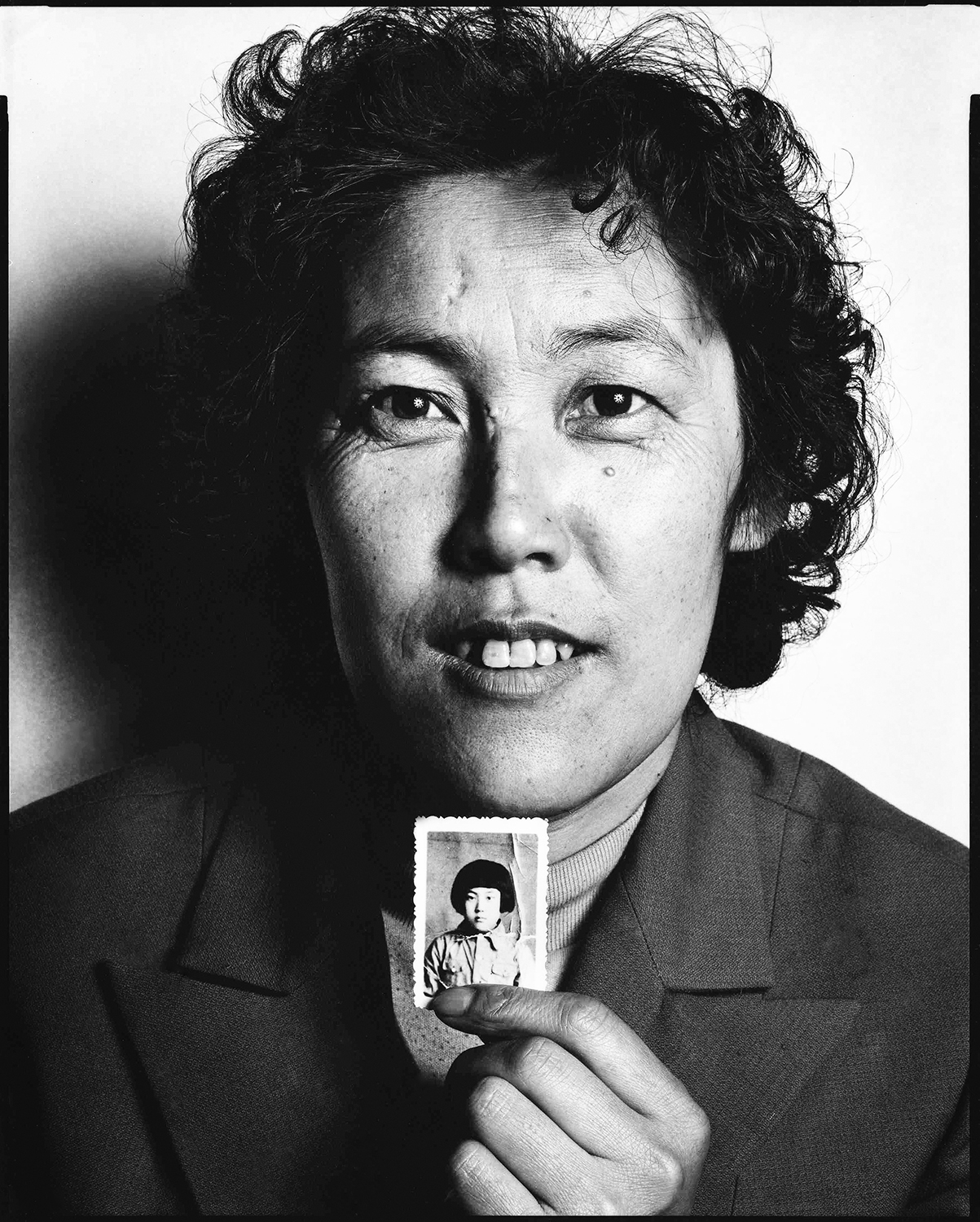

- 李 玉琴/四平省/第2次訪日(昭和57年2月)P-426

-

- 張 秀芹/間島省/第7次訪日(昭和60年2月)P-418

-

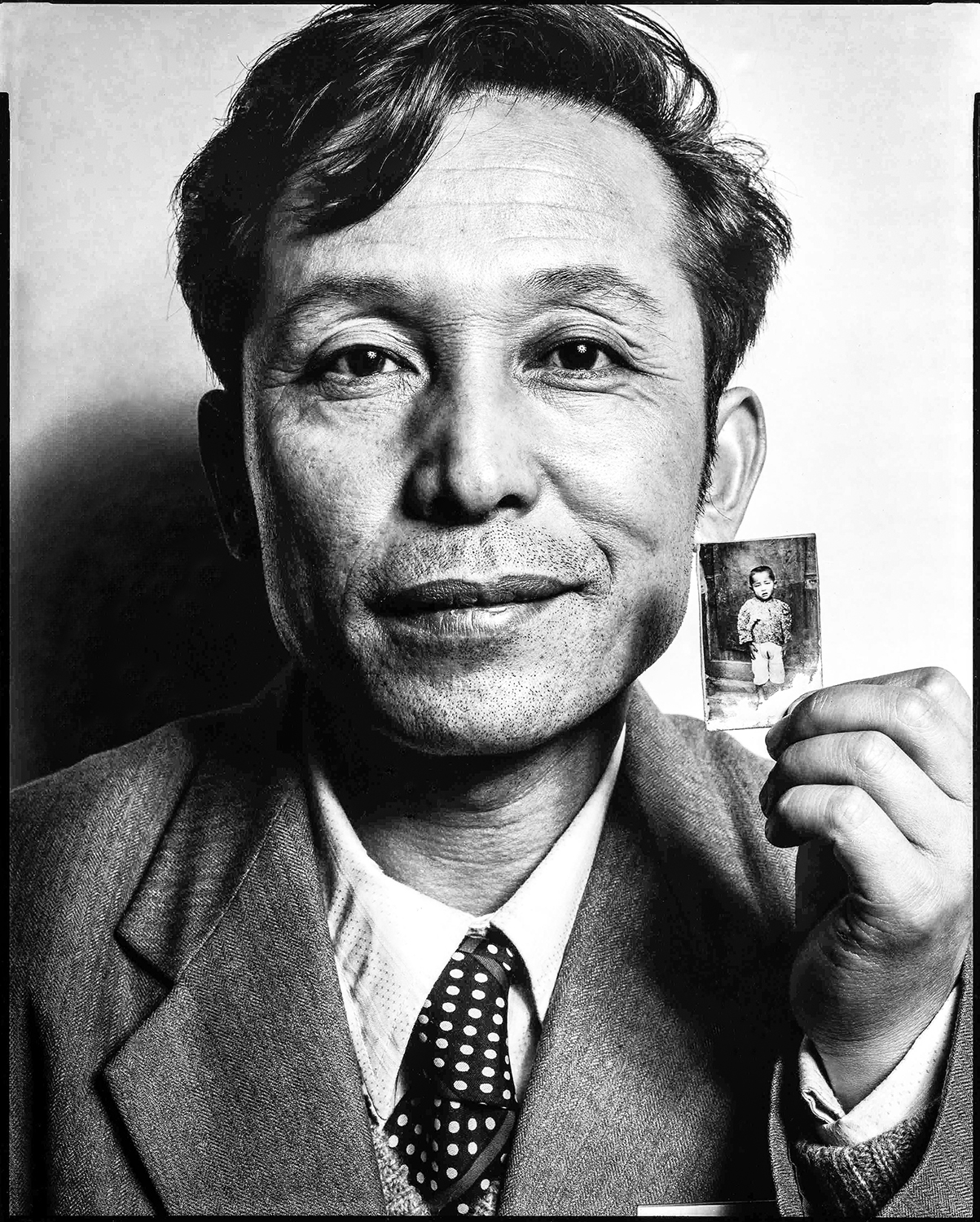

- 王 吉発/吉林省/第7次訪日(昭和60年2月)P-988

-

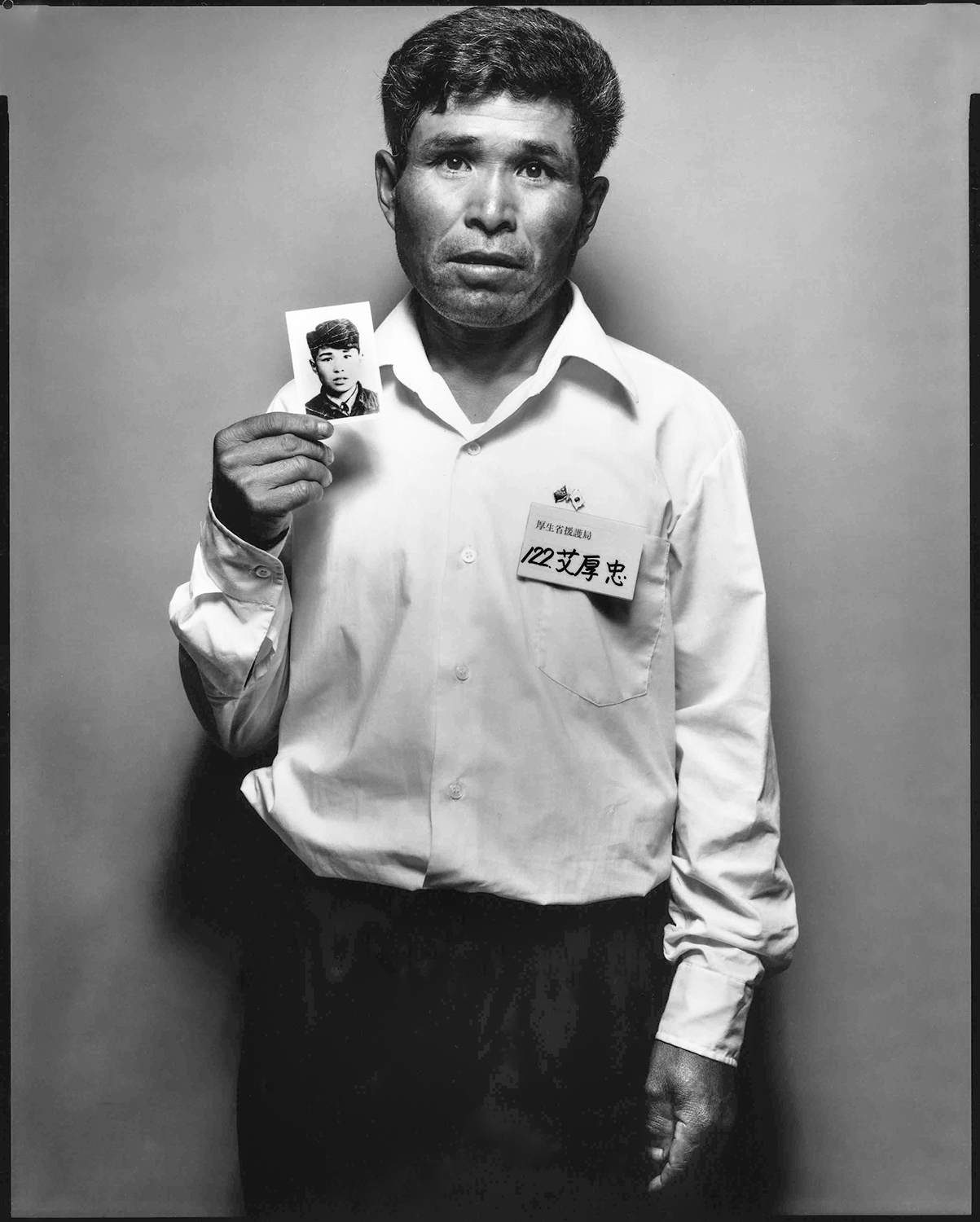

- 艾 厚忠/東安省/第11次訪日(昭和61年6月)P-792

-

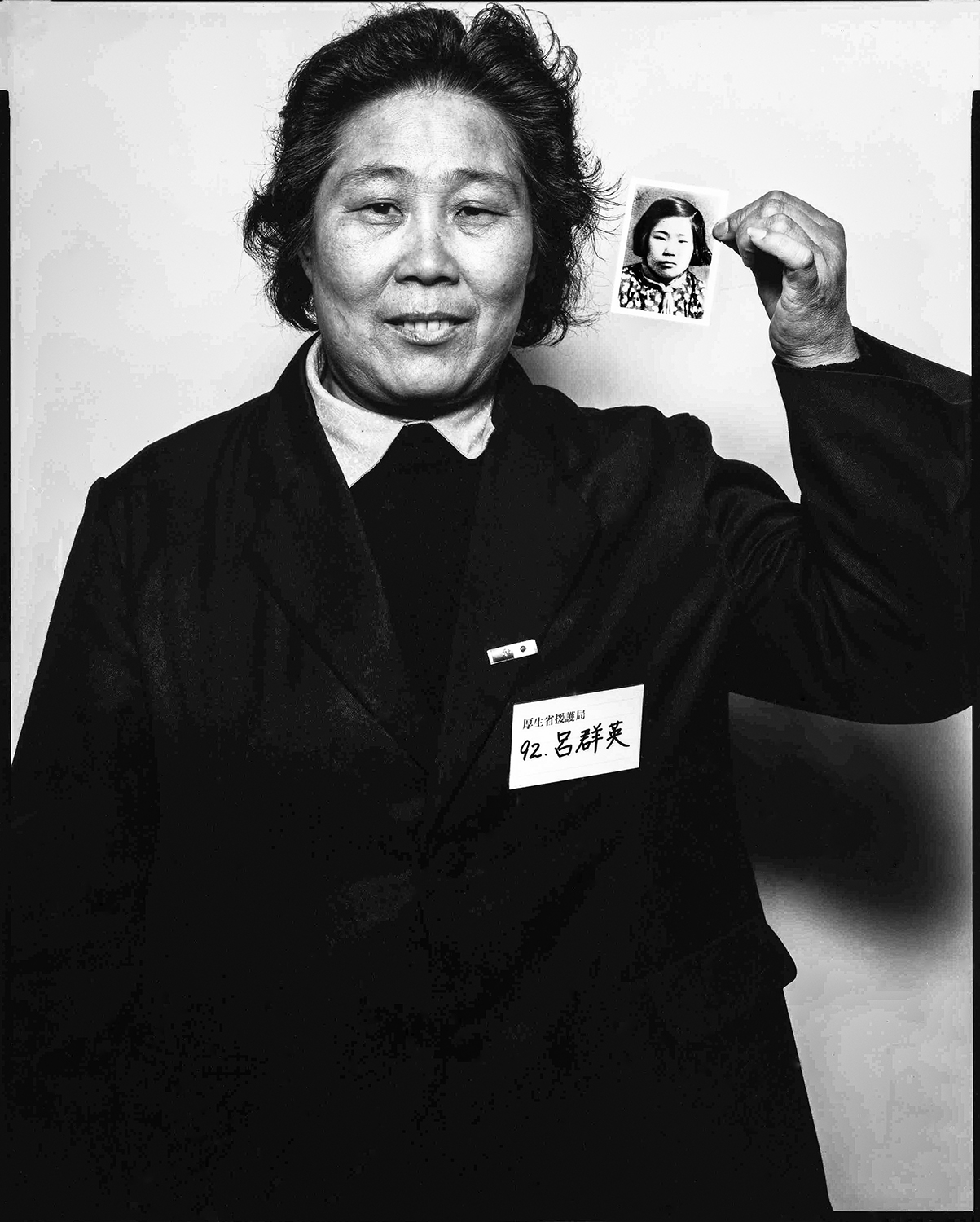

- 呂 群英/関東省/第15次訪日(昭和62年2月)P-599

-

- 隋 徳金/浜江省/第6次訪日(昭和59年11月)P-865

-

- 韓 麗娟/吉林省/第7次訪日(昭和60年2月)P-396

-

- 馬 千義/奉天省/第7次訪日(昭和60年2月)P-1151

-

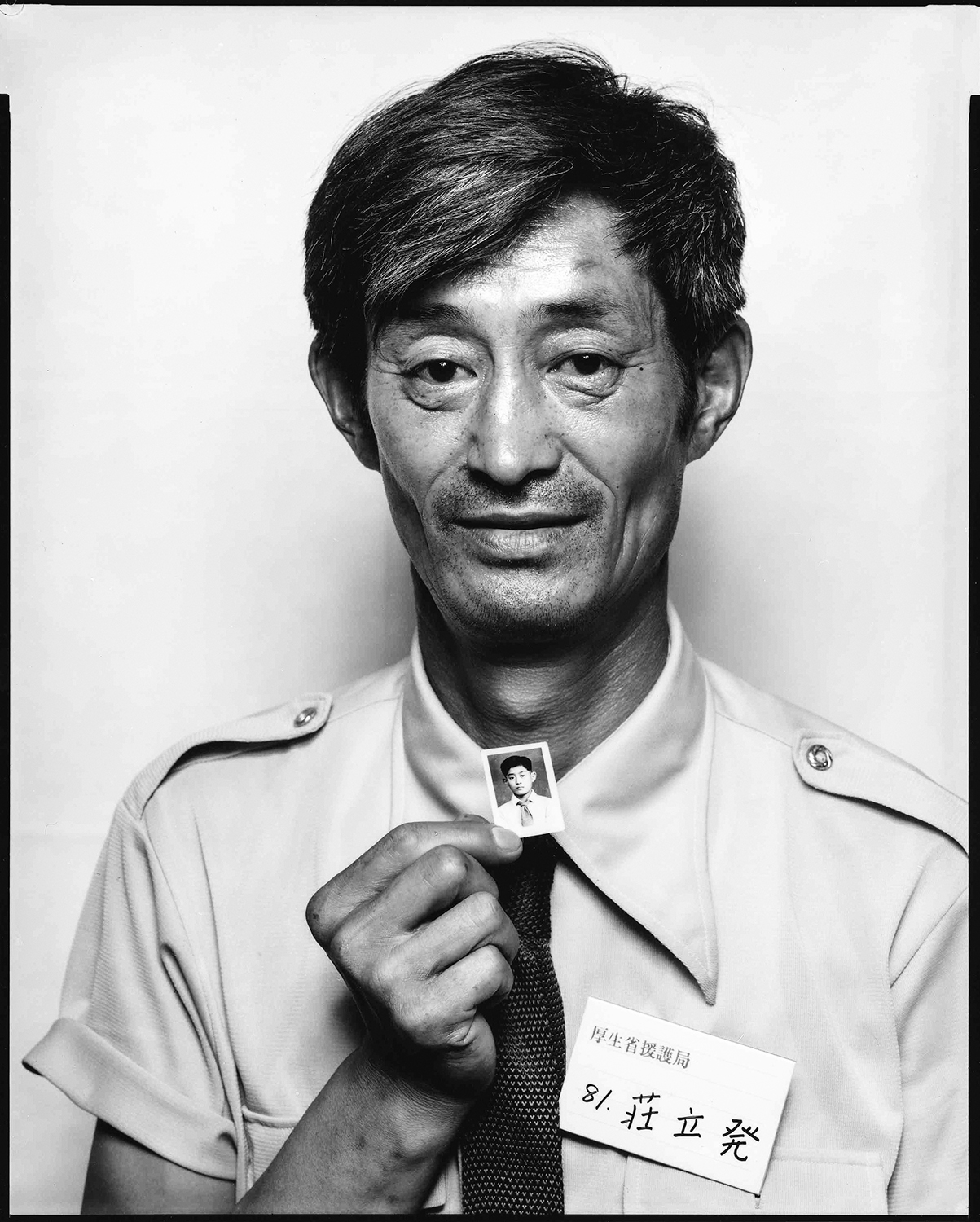

- 荘 立発/奉天省/第8次訪日(昭和60年9月)P-1133

-

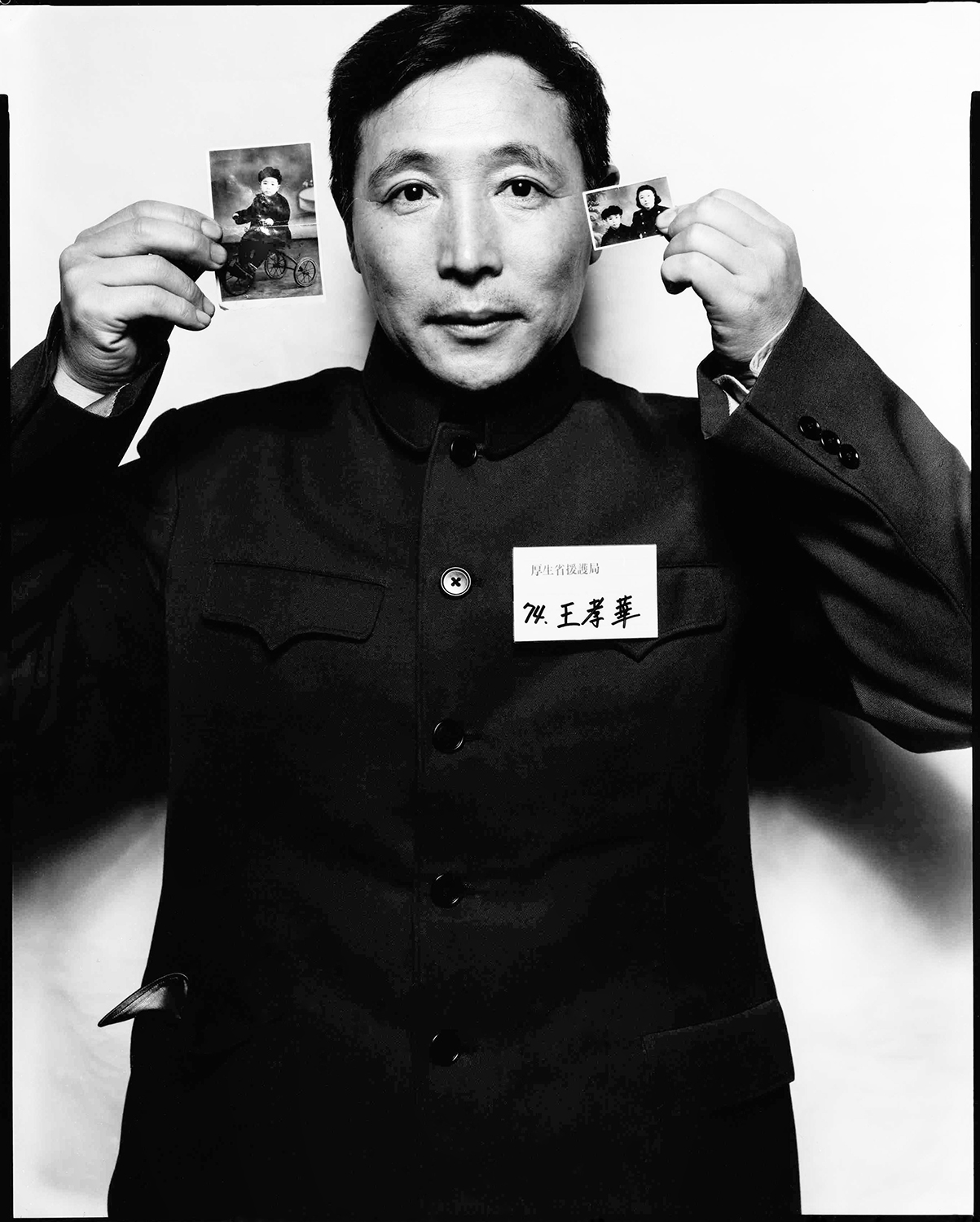

- 王 孝華/奉天省/第10次訪日(昭和61年2月)P-1146

-

- 李 蘭秋/安東省/第2次訪日(昭和57年2月)P-590

-

- 程 士英/竜江省/第9次訪日(昭和60年11月)P-32

-

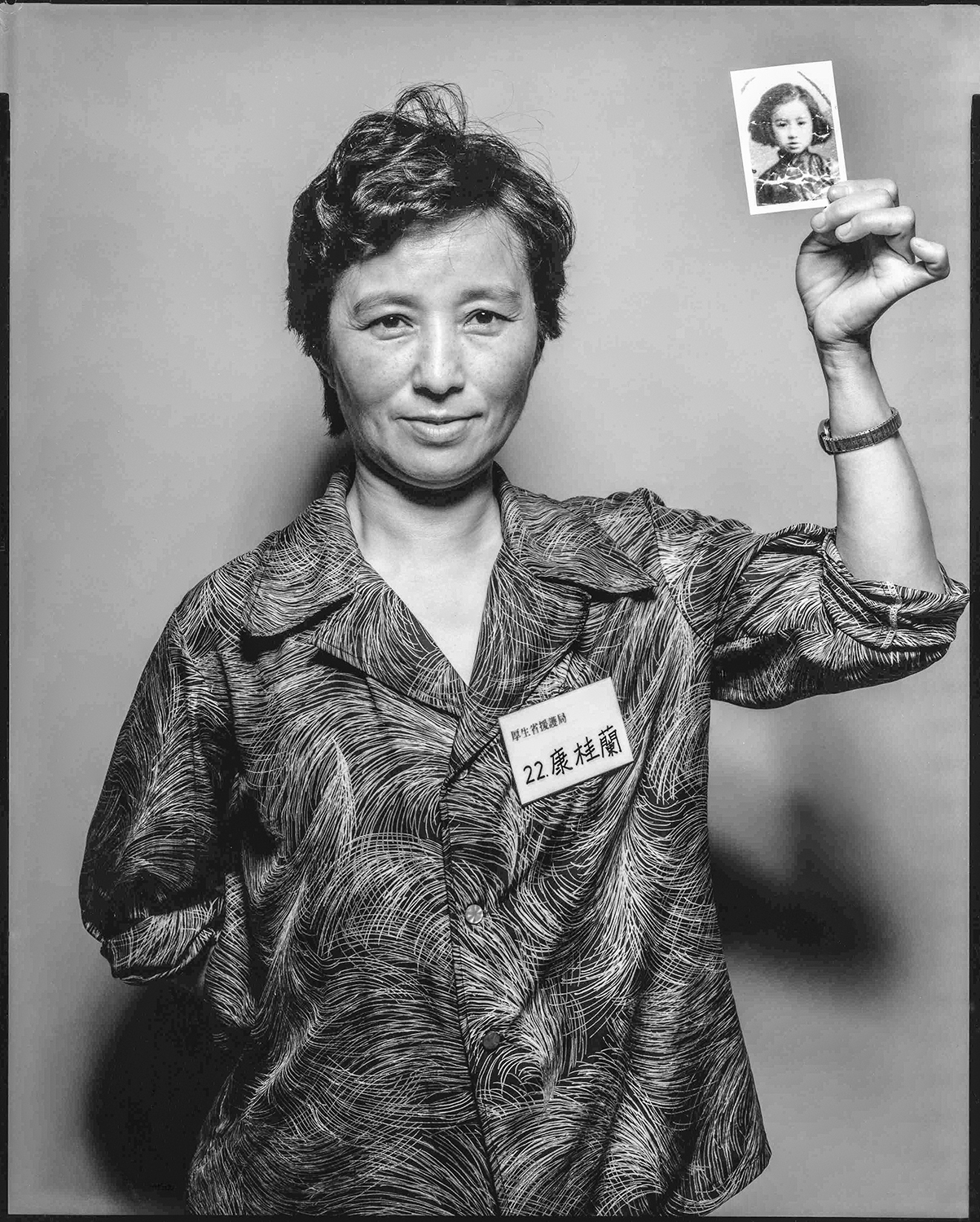

- 康 桂蘭/浜江省/第12次訪日(昭和61年9月)P-179

-

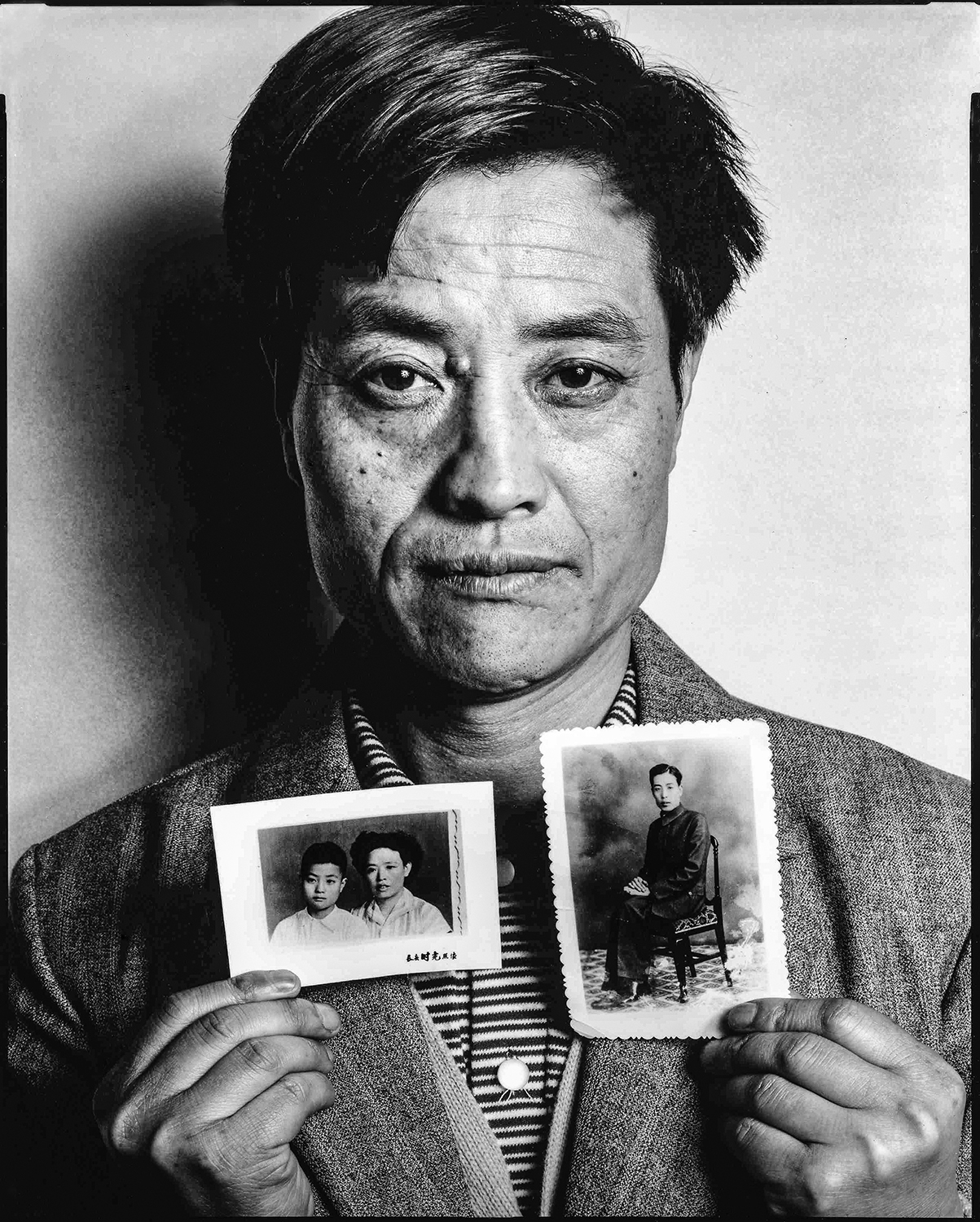

- 張 書林/奉天省/第7次訪日(昭和60年2月)P-1123

-

- 邢 書芬/安東省/第6次訪日(昭和59年11月)P-586

A ledger that answers history

Ide Magoroku

The peace and friendship treaty between Japan and China was signed on August 12, 1978, thirty-three years after the end of World War II. As is well known, in August 1945, amidst the chaos of defeat, many Japanese children were left behind on the Chinese mainland, especially in the former Manchuria (Northeast region), separated from their parents. Children aged from zero to sixth grade at the time of the defeat were raised by foster parents in that region until the treaty was signed thirty-three years later, having reached adulthood. However, since most were separated from their parents at a young age, their whereabouts became unknown.

The Ministry of Health began investigations for finding these relatives in March 1981, three years after the treaty was signed. Despite the passage of thirty-six years since the war’s end, which presented a significant barrier, only twenty-six out of the first group of forty-seven people were identified. The rate of identification, which was initially close to 70%, gradually decreased over time, with subsequent visits to Japan for the same purpose, and it was no longer unusual for the rate to fall below 30%.

The fifteenth investigation in March 1987 was intended to be the final one, but it was later found that there were still uninvestigated people in northeastern China, leading to ongoing supplementary investigations. The identification rate for these individuals has fallen to below 20%. From the first to the twentieth investigation, 1,726 individuals were examined, with 1,092 still unidentified, making the identification rate 63.3%.

The Ministry of Health began investigations for finding these relatives in March 1981, three years after the treaty was signed. Despite the passage of thirty-six years since the war’s end, which presented a significant barrier, only twenty-six out of the first group of forty-seven people were identified. The rate of identification, which was initially close to 70%, gradually decreased over time, with subsequent visits to Japan for the same purpose, and it was no longer unusual for the rate to fall below 30%.

The fifteenth investigation in March 1987 was intended to be the final one, but it was later found that there were still uninvestigated people in northeastern China, leading to ongoing supplementary investigations. The identification rate for these individuals has fallen to below 20%. From the first to the twentieth investigation, 1,726 individuals were examined, with 1,092 still unidentified, making the identification rate 63.3%.

The fact that many of these people remained in a foreign country, having lost their birth names amid unavoidable chaos, starkly reminds us of the cruelty of war. Most of these individuals are descendants of the "Manchuria-Mongolia Settlement Group," sent to the frontiers of the imperialist era's Manchuria, left behind in the confusion around the defeat, pointing to the errors of Japan's continental aggression policy over half a century ago.

Yet, we must also reflect deeply on the history of leaving these young compatriots in a foreign land for over thirty years, trapped by the realities of post-war international politics and the Cold War structure. In this sense, the unidentified individuals' cries of "Who am I?" echo as a profound question to our history.

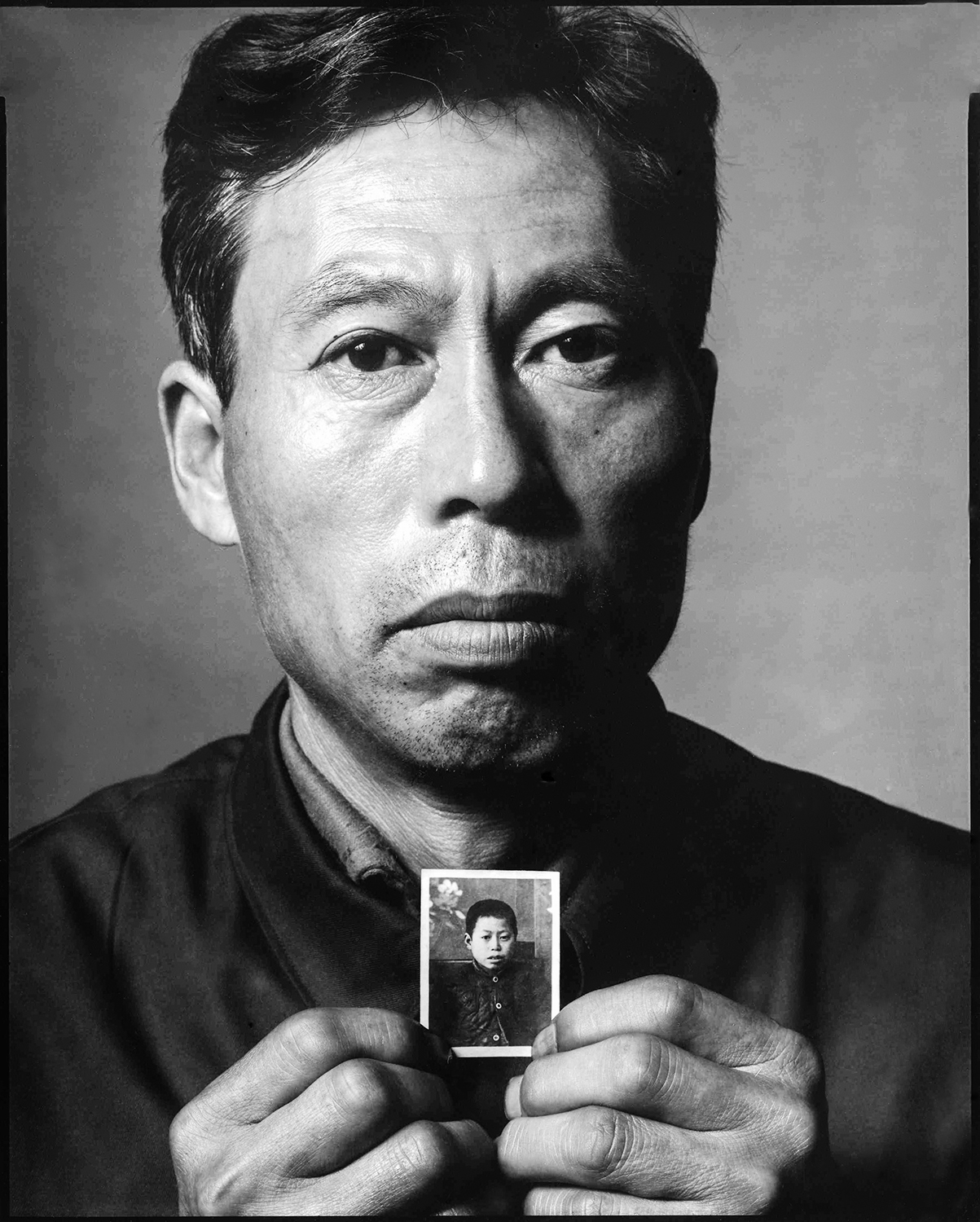

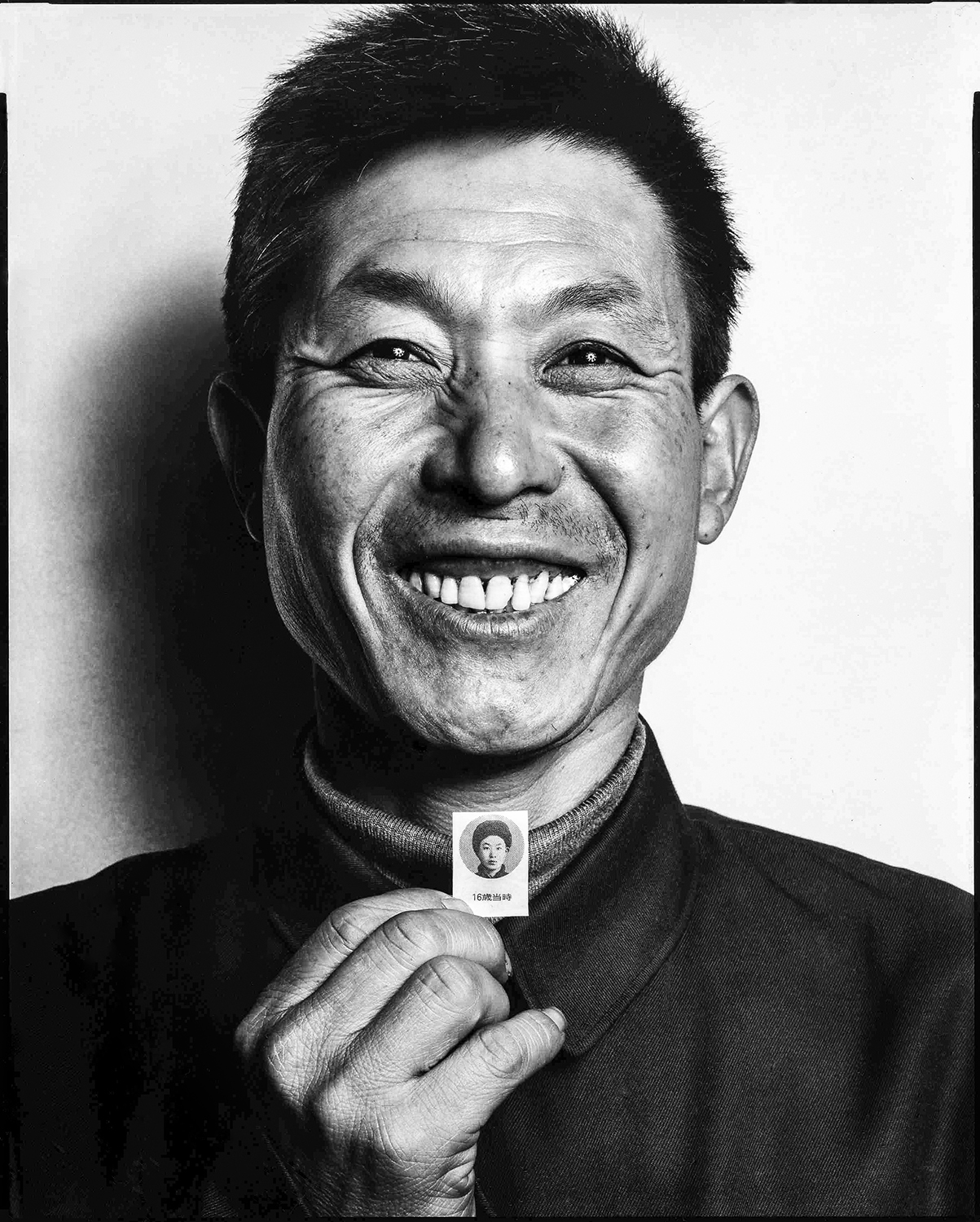

Photographer ARAMASA Taku born in 1936 and spent his early years in Jamsu City, Manchuria, narrowly avoided being left behind after the war. ARAMASA's transition from a fashion photographer to capturing the faces of those involved in the investigations since 1981 reflects a deep connection to this story. The accumulated photographs, charged with emotion at every shutter click, make up this book. The efforts of those involved in the identity investigations since 1981 have been substantial, yet constrained by the two-week duration of each investigative period.

ARAMASA's photographs, captured with a specially commissioned large-format camera for portraiture, unlike small newspaper photos or fleeting TV camera images, record fine details fully, covering the long oblivion of historical time. They qualify as the sole ledger capable of answering the question, "Who am I?"

We aim to place this powerful "ledger" at municipal offices across Japan, hoping that the detailed features captured here will lead to the identification of as many individuals as possible, bringing their voices to the entire nation. / GPT-4

Yet, we must also reflect deeply on the history of leaving these young compatriots in a foreign land for over thirty years, trapped by the realities of post-war international politics and the Cold War structure. In this sense, the unidentified individuals' cries of "Who am I?" echo as a profound question to our history.

Photographer ARAMASA Taku born in 1936 and spent his early years in Jamsu City, Manchuria, narrowly avoided being left behind after the war. ARAMASA's transition from a fashion photographer to capturing the faces of those involved in the investigations since 1981 reflects a deep connection to this story. The accumulated photographs, charged with emotion at every shutter click, make up this book. The efforts of those involved in the identity investigations since 1981 have been substantial, yet constrained by the two-week duration of each investigative period.

ARAMASA's photographs, captured with a specially commissioned large-format camera for portraiture, unlike small newspaper photos or fleeting TV camera images, record fine details fully, covering the long oblivion of historical time. They qualify as the sole ledger capable of answering the question, "Who am I?"

We aim to place this powerful "ledger" at municipal offices across Japan, hoping that the detailed features captured here will lead to the identification of as many individuals as possible, bringing their voices to the entire nation. / GPT-4

歴史に答える台帳 井出孫六

日中間に平和友好条約が締結されたのは一九七八年八月十二日のことです。第二次大戦終了から三十三年の歳月が流れていました。

周知のように、一九四五年八月、中国大陸とくに旧満州(東北地方)には敗戦の混乱のなか多くの日本人子女が肉親と別れて取り残されたのですが、敗戦当時零歳から小学校六年生までの子どもたちは、平和条約の締結されるまでの三十三年間、彼の地で養父母に育てられ、成人しておりましたけれども、大部分の人たちが幼くして肉親と別れたため、身許がわからなくなっていました。

肉親探しのための訪日調査が、厚生省の手で始められたのは、平和条約が締結された三年後の一九八一年三月のことでした。敗戦から三十六年という歳月の経過が大きな壁となって、第一陣四十七名のうち身許が判明した方は二十六名でした。以来、毎年二、三回のペースで肉親探しのための訪日調査がつづけられ、その都度、新聞・テレビに大きく報道されましたが、回を重ねるにつれて判明率は逓減し、初めのうちは七〇パーセント近かった判明率もついには三〇パーセントをきることも珍しくなくなってきました。

一九八七年三月第十五次の調査をもって、訪日は一応のピリオドがうたれることになりましたが、その後もなお、中国東北部を中心に未調査の人びとが残っていることが判明し、なおひきつづき補充調査が重ねられて今日にいたっております。これらの方々の身許判明率は二〇パーセントをきるようなことにもなっております。第一次訪日調査から第二〇次の訪日調査まで、一七二六名の方々が調査の対象となりましたが、依然身許の判明していない方々は一○九二名、率にして六三・三パーセントとなっております。

周知のように、一九四五年八月、中国大陸とくに旧満州(東北地方)には敗戦の混乱のなか多くの日本人子女が肉親と別れて取り残されたのですが、敗戦当時零歳から小学校六年生までの子どもたちは、平和条約の締結されるまでの三十三年間、彼の地で養父母に育てられ、成人しておりましたけれども、大部分の人たちが幼くして肉親と別れたため、身許がわからなくなっていました。

肉親探しのための訪日調査が、厚生省の手で始められたのは、平和条約が締結された三年後の一九八一年三月のことでした。敗戦から三十六年という歳月の経過が大きな壁となって、第一陣四十七名のうち身許が判明した方は二十六名でした。以来、毎年二、三回のペースで肉親探しのための訪日調査がつづけられ、その都度、新聞・テレビに大きく報道されましたが、回を重ねるにつれて判明率は逓減し、初めのうちは七〇パーセント近かった判明率もついには三〇パーセントをきることも珍しくなくなってきました。

一九八七年三月第十五次の調査をもって、訪日は一応のピリオドがうたれることになりましたが、その後もなお、中国東北部を中心に未調査の人びとが残っていることが判明し、なおひきつづき補充調査が重ねられて今日にいたっております。これらの方々の身許判明率は二〇パーセントをきるようなことにもなっております。第一次訪日調査から第二〇次の訪日調査まで、一七二六名の方々が調査の対象となりましたが、依然身許の判明していない方々は一○九二名、率にして六三・三パーセントとなっております。

やむなき混乱のなかでとはいえ、これらの多くの人たちが自分の生得の名前を失ったまま異国に残されたことを考えますと、あらためて戦争のむごさを思わずにはいられません。周知のように、これらの人びとの大多数が、帝国主義時代の旧満州に「満蒙開拓団」として辺境の地へと送りだされていった方々の子女であり、敗戦前後の混乱のなかで放置されていった状況は明らかになってきていますが、問題のよってくるところのものは、半世紀以上遡ってわが国の大陸侵略政策の過誤に求められなければなりません。

しかしまた、同時に、世界の冷戦構造という戦後の国際政治の現実の壁にはばまれてのこととはいえ、異国にとり残されたままの幼い同胞の存在を、そのまま三十余年放置してきてしまった歴史をも深く顧みなければならないと思うのです。

そのような意味において、身許未判明の方々の、「私は誰ですか?」という叫びは、わたしたちの歴史にむけての問いかけではないだろうかと、受けとめずにはいられないのです。

写真家新正卓さんは、一九三六年の生まれです。幼少年期を旧満州のチャムス市ですごしたとうかがっています。紙一重の差で敗戦の翌年、新正さんは日本に引き揚げてきましたが、一歩まちがえば彼の地にとどまる運命をになったかもしれない少年の一人でありました。その新正さんが、ファッション・カメラマンであることをやめ、パリから戻って、一九八一年に始まった訪日調査の人びとの写真を撮りつづけてきた気持ちがわかるような気がします。一回一回、シャッターを押す指にその気持ちがこめられていた、その結果集積された写真が本書に盛られることになったのです。 一九八一年から始まって今日におよんでいる身許調査に費やされた関係者の努力はなみ大抵のものではありませんでした。しかし、毎度、調査期間は二週間の滞在という時間的制約をもっていましたから、費やされる努力にも限りがありました。新正卓さんの写真にはその時間的制約をカヴァーする何ものかが付与されているように思われます。肖像写真用に特注した大型カメラに写しだされた写真には、新聞に掲載された小さな顔写真や、瞬間的に消えさるテレビカメラとはちがって、微細な特徴が十全に記録されることともなりました。それは、歴史の長い時間の忘却をもカヴァーする力をも持っております。「私は誰ですか?」という問いかけに答える唯一の台帳の資格を有するものといってよいでしょう。

わたしたちは、この有力な「台帳」を、日本全国の自治体の窓口に置いて、「私は誰ですか?」と尋ねている人びとの声を、日本全国に届けたいと思いたちました。ここに写しだされた微細な特徴がきっかけになって、一人でも多くの方々の身許が判明することを願うばかりです。

しかしまた、同時に、世界の冷戦構造という戦後の国際政治の現実の壁にはばまれてのこととはいえ、異国にとり残されたままの幼い同胞の存在を、そのまま三十余年放置してきてしまった歴史をも深く顧みなければならないと思うのです。

そのような意味において、身許未判明の方々の、「私は誰ですか?」という叫びは、わたしたちの歴史にむけての問いかけではないだろうかと、受けとめずにはいられないのです。

写真家新正卓さんは、一九三六年の生まれです。幼少年期を旧満州のチャムス市ですごしたとうかがっています。紙一重の差で敗戦の翌年、新正さんは日本に引き揚げてきましたが、一歩まちがえば彼の地にとどまる運命をになったかもしれない少年の一人でありました。その新正さんが、ファッション・カメラマンであることをやめ、パリから戻って、一九八一年に始まった訪日調査の人びとの写真を撮りつづけてきた気持ちがわかるような気がします。一回一回、シャッターを押す指にその気持ちがこめられていた、その結果集積された写真が本書に盛られることになったのです。 一九八一年から始まって今日におよんでいる身許調査に費やされた関係者の努力はなみ大抵のものではありませんでした。しかし、毎度、調査期間は二週間の滞在という時間的制約をもっていましたから、費やされる努力にも限りがありました。新正卓さんの写真にはその時間的制約をカヴァーする何ものかが付与されているように思われます。肖像写真用に特注した大型カメラに写しだされた写真には、新聞に掲載された小さな顔写真や、瞬間的に消えさるテレビカメラとはちがって、微細な特徴が十全に記録されることともなりました。それは、歴史の長い時間の忘却をもカヴァーする力をも持っております。「私は誰ですか?」という問いかけに答える唯一の台帳の資格を有するものといってよいでしょう。

わたしたちは、この有力な「台帳」を、日本全国の自治体の窓口に置いて、「私は誰ですか?」と尋ねている人びとの声を、日本全国に届けたいと思いたちました。ここに写しだされた微細な特徴がきっかけになって、一人でも多くの方々の身許が判明することを願うばかりです。

Portrait of 1,092 People

Syuichi Sae

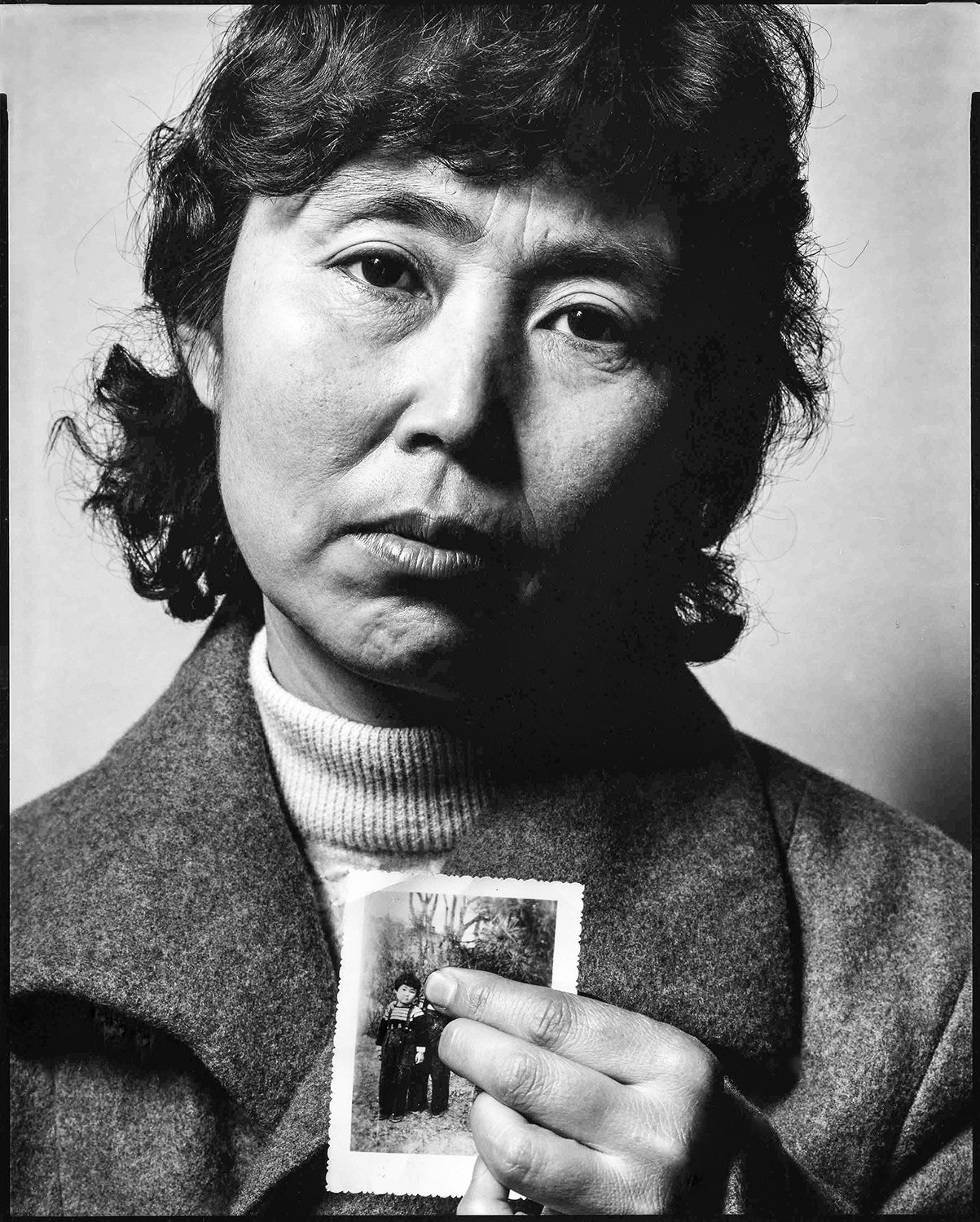

In the past two months, it has become a book I constantly refer to. Its large format, nearly a half-cut size with a thickness of five centimeters, carries not just physical heft but a profound emotional weight that resonates deep within. Each page features a monochrome half-body portrait of one of the 1,092 individuals, men and women alike, all staring directly ahead. Titled “Who Am I,” this collection comprises portrait photographs of Japanese orphans left behind in China.

The photographer, ARAMASA Taku is someone I worked with during a trip to India about a decade ago. At that time, he had transitioned from commercial fashion photography to the arduous task of documenting social themes. Following his photographic exhibition and book publication, “Distant Motherland,” which chronicled the lives of first-generation South American immigrants and earned him the Domon Ken Award in 1985, he had already begun photographing these individuals when the first group of Chinese left-behind Japanese orphans visited Japan in March 1981. Born in 1936, ARAMASA could have become one of these orphans himself, having faced defeat in former Manchuria at the age of nine amidst a harrowing escape. Additionally, a woman who had been like a mother to him went missing, only for them to reunite suddenly after more than thirty years. “At that time, I reconsidered the essence of photography,” he recounted to me by the Ganges River. Severing ties with the glamorous world of fashion photography, he overlaid his personal experiences onto those of the visiting Chinese left-behind Japanese orphans, bringing his large camera to every meeting and continuing to capture their portraits over nine years, up to the twentieth group’s visit to their homeland in February 1990.

The photographer, ARAMASA Taku is someone I worked with during a trip to India about a decade ago. At that time, he had transitioned from commercial fashion photography to the arduous task of documenting social themes. Following his photographic exhibition and book publication, “Distant Motherland,” which chronicled the lives of first-generation South American immigrants and earned him the Domon Ken Award in 1985, he had already begun photographing these individuals when the first group of Chinese left-behind Japanese orphans visited Japan in March 1981. Born in 1936, ARAMASA could have become one of these orphans himself, having faced defeat in former Manchuria at the age of nine amidst a harrowing escape. Additionally, a woman who had been like a mother to him went missing, only for them to reunite suddenly after more than thirty years. “At that time, I reconsidered the essence of photography,” he recounted to me by the Ganges River. Severing ties with the glamorous world of fashion photography, he overlaid his personal experiences onto those of the visiting Chinese left-behind Japanese orphans, bringing his large camera to every meeting and continuing to capture their portraits over nine years, up to the twentieth group’s visit to their homeland in February 1990.

Among these, 606 individuals were identified and reunited with their families, which means a staggering 64 percent returned home without any knowledge of their Japanese names or families, their roots completely severed. "Who Am I" documents these people. Each face, whether in their forties or fifties, seems to be frozen in time at the moment of separation immediately after Japan's defeat in 1945, earnestly searching for their relatives filled with sorrow yet hope, speaking quietly rather than shouting. Unlike the fleeting images seen on television screens or the small photographs printed in newspapers, their expressions capture subtle details, conveying the vivid presence of humans beyond the forgotten spans of history.

However, publishing this photobook was no easy task. It might seem like a government responsibility, but a publishing committee had to raise funds nationwide and, despite shortages, managed to realize the project with volunteer support. Since August, it has been made available in municipal offices across the country, serving as a ledger for those searching for their relatives. Although having it on my desk doesn't directly aid their search, I find myself drawn to it, flipping through the pages, unable to look away from each individual.

One woman, named Liu Yuxiang, stands with a faint smile, holding a small photo of a young girl in her right hand. She wears a newly tailored, somewhat oversized dark suit, with the sleeves rolled up about five centimeters—likely due to the length being too long. "Estimated age as of August 1945: 4 years. Blood type: B. Place of separation: Tieshou County, Hei'an Province. Date of separation: around October 1945. Japanese name: unknown. Family composition: father, mother, brother. Occupation of parents/family: settlers. Living situation with family: unknown. Circumstance of separation: carried on the back by the mother, who was leading a boy thought to be her brother, to the home of foster father Liu Chunfang, near the station in Suiso County. Wearing a blue chan-chan-co at the time. Later, the mother visited the foster home with a boy about seven or eight years old but could not meet." This is all that is recorded.

Many of the orphans were children of people sent to Manchukuo and Inner Mongolia for settlement, and she was one of them. At that time, estimated to be four years old, she could not remember her Japanese name or her parents' names. A note in the margin states, "The photo she holds was taken when she was nine years old," likely in her foster home. Though old and faded, and so fragile it seems it could crumble at the slightest touch, the photo captures a young girl with plump cheeks—a photo that would make her family exclaim with recognition upon seeing it. Her innocent gaze seems to be reflected in the nearly fifty-year-old Liu Yuxiang's smiling face...

Tan Yongfu is another individual featured in this profound collection. His coat, with sleeves rolled up, seems tailored for a woman rather than a man. His rugged expression, as if he has just looked up from the vast lands of the continent, is complemented by a faint mustache below his nose. All details about him at the time of Japan's defeat—his Japanese name, his parents' occupations, his family structure, and his living situation—are marked as "unknown." A notable physical feature is "two moles between the eyebrows." "In October 1946, his mother left him at the home of his foster parents (a Russian-style building) in Yiner Beach City, South Gangmu Street, under the care of foster mother Quxian Ju." This is all his record states. He has no childhood photos or any clues to his past. The man, now years beyond forty, looks older than his age, his hands gnarled, as he looks tensely into the camera...

This passage reminds me of my own story. In September 1944, as Japan's situation in the Pacific War darkened, I took a commemorative photo with my family. Just days before I, a fifth grader at the national school, was separated from my parents and siblings to escape the bombings of Tokyo for a small town in the northeast, we had our picture taken, prepared for the possibility that we might never see each other alive again, a common practice among our neighbors. Fortunately, my family survived the Great Tokyo Air Raid on March 10 of the following year, and after the war, I was reunited with them, unlike some friends who became war orphans and wandered the ruins seeking their parents with just a photo as their clue.

A photo taken on a special day, with everyone facing the camera tensely, is a testament to those times. Today, while taking photos has become a common part of daily life, those uninteresting-looking portrait photos taken on special occasions represent the essence of photography as an art form. They quietly convey profound life stories that go beyond mere words, more so than casual, candid shots capturing natural expressions.

These 1,092 portraits, after 45 years since the war, continue to mark the ongoing tragedy of war, asking "Who am I?"—seeking proof of existence not only from relatives but also from all Japanese who tend to forget the war. As the investigations related to the visits of these orphans conclude and their issue fades from the media, it becomes even more crucial not to forget these facts.

In the void of the white background, images of the Chinese foster parents and families who raised them, the landscapes of China, and those who have become fathers and mothers to the orphans who have yet to visit Japan, rise up. While we wish to reunite them with their biological families, many of those present here may end their lives as Chinese without ever proving their roots. The complexity of knowing yet not coming forward adds depth to their portraits, each silently conveying a lifetime shaped by an unending war. This book, a constant reference on my desk, presents a depth that I could spend a lifetime exploring without fully comprehending. / GPT-4

However, publishing this photobook was no easy task. It might seem like a government responsibility, but a publishing committee had to raise funds nationwide and, despite shortages, managed to realize the project with volunteer support. Since August, it has been made available in municipal offices across the country, serving as a ledger for those searching for their relatives. Although having it on my desk doesn't directly aid their search, I find myself drawn to it, flipping through the pages, unable to look away from each individual.

One woman, named Liu Yuxiang, stands with a faint smile, holding a small photo of a young girl in her right hand. She wears a newly tailored, somewhat oversized dark suit, with the sleeves rolled up about five centimeters—likely due to the length being too long. "Estimated age as of August 1945: 4 years. Blood type: B. Place of separation: Tieshou County, Hei'an Province. Date of separation: around October 1945. Japanese name: unknown. Family composition: father, mother, brother. Occupation of parents/family: settlers. Living situation with family: unknown. Circumstance of separation: carried on the back by the mother, who was leading a boy thought to be her brother, to the home of foster father Liu Chunfang, near the station in Suiso County. Wearing a blue chan-chan-co at the time. Later, the mother visited the foster home with a boy about seven or eight years old but could not meet." This is all that is recorded.

Many of the orphans were children of people sent to Manchukuo and Inner Mongolia for settlement, and she was one of them. At that time, estimated to be four years old, she could not remember her Japanese name or her parents' names. A note in the margin states, "The photo she holds was taken when she was nine years old," likely in her foster home. Though old and faded, and so fragile it seems it could crumble at the slightest touch, the photo captures a young girl with plump cheeks—a photo that would make her family exclaim with recognition upon seeing it. Her innocent gaze seems to be reflected in the nearly fifty-year-old Liu Yuxiang's smiling face...

Tan Yongfu is another individual featured in this profound collection. His coat, with sleeves rolled up, seems tailored for a woman rather than a man. His rugged expression, as if he has just looked up from the vast lands of the continent, is complemented by a faint mustache below his nose. All details about him at the time of Japan's defeat—his Japanese name, his parents' occupations, his family structure, and his living situation—are marked as "unknown." A notable physical feature is "two moles between the eyebrows." "In October 1946, his mother left him at the home of his foster parents (a Russian-style building) in Yiner Beach City, South Gangmu Street, under the care of foster mother Quxian Ju." This is all his record states. He has no childhood photos or any clues to his past. The man, now years beyond forty, looks older than his age, his hands gnarled, as he looks tensely into the camera...

This passage reminds me of my own story. In September 1944, as Japan's situation in the Pacific War darkened, I took a commemorative photo with my family. Just days before I, a fifth grader at the national school, was separated from my parents and siblings to escape the bombings of Tokyo for a small town in the northeast, we had our picture taken, prepared for the possibility that we might never see each other alive again, a common practice among our neighbors. Fortunately, my family survived the Great Tokyo Air Raid on March 10 of the following year, and after the war, I was reunited with them, unlike some friends who became war orphans and wandered the ruins seeking their parents with just a photo as their clue.

A photo taken on a special day, with everyone facing the camera tensely, is a testament to those times. Today, while taking photos has become a common part of daily life, those uninteresting-looking portrait photos taken on special occasions represent the essence of photography as an art form. They quietly convey profound life stories that go beyond mere words, more so than casual, candid shots capturing natural expressions.

These 1,092 portraits, after 45 years since the war, continue to mark the ongoing tragedy of war, asking "Who am I?"—seeking proof of existence not only from relatives but also from all Japanese who tend to forget the war. As the investigations related to the visits of these orphans conclude and their issue fades from the media, it becomes even more crucial not to forget these facts.

In the void of the white background, images of the Chinese foster parents and families who raised them, the landscapes of China, and those who have become fathers and mothers to the orphans who have yet to visit Japan, rise up. While we wish to reunite them with their biological families, many of those present here may end their lives as Chinese without ever proving their roots. The complexity of knowing yet not coming forward adds depth to their portraits, each silently conveying a lifetime shaped by an unending war. This book, a constant reference on my desk, presents a depth that I could spend a lifetime exploring without fully comprehending. / GPT-4

Shinchosha, November 1990 issue, "Mado" by Shuichi Sae

一千九十二人の肖像 佐江衆一

このふた月、それは座右の書になった。ほぼ新開半裁の大判で、厚さ五センチ、ずっしり持ち重りするだけでなく、心の奥深くへ迫ってくる重さだ。一頁に一人ずつ、一千九十二人の男女モノクロ半身像が、正面をじっと見つめて並んでいる。『私は誰ですか』と題された、中国残留日本人孤児の肖像写真集である。

撮影者は新正卓氏。彼とインド旅行で一緒に仕事をしたのは、十年ほど前だった。その頃、新正氏はファッション専門のコマーシャルフォトから社会的テーマの地道なきびしい仕事に変った時期だった。その後、一九八五年、数年にわたって撮りつづけた南米移民一世の肖像『遥かなる祖国』の写真展を開き写真集を出版、土門拳賞を受けたのだが、八一年三月、第一次中国残留孤児訪日のときから、この人たちの写真を撮りはじめていた。昭和十一年生れの彼は、九歳のとき旧北満で敗戦をむかえ、悲惨な逃避行のなかで残留孤児になったかもしれない経験をもつだけでなく、母親がわりの女性が行方不明になり、戦後三十余年ぶりに突然便りがあり再会したという。「このとき、写真の在り方を探く考えなおした」と、ガンジス川の畔できいた。華やかなファッション写真家と決別した彼は、自分の人生を重ねるようにして、中国残留日本人孤児が訪日するたびに調査会場へ大型カメラを持ち込み、今年九〇年二月に祖国を訪れた第二十次の人びとまで、九年間にわたって肖像写真を撮りつづけた。

撮影者は新正卓氏。彼とインド旅行で一緒に仕事をしたのは、十年ほど前だった。その頃、新正氏はファッション専門のコマーシャルフォトから社会的テーマの地道なきびしい仕事に変った時期だった。その後、一九八五年、数年にわたって撮りつづけた南米移民一世の肖像『遥かなる祖国』の写真展を開き写真集を出版、土門拳賞を受けたのだが、八一年三月、第一次中国残留孤児訪日のときから、この人たちの写真を撮りはじめていた。昭和十一年生れの彼は、九歳のとき旧北満で敗戦をむかえ、悲惨な逃避行のなかで残留孤児になったかもしれない経験をもつだけでなく、母親がわりの女性が行方不明になり、戦後三十余年ぶりに突然便りがあり再会したという。「このとき、写真の在り方を探く考えなおした」と、ガンジス川の畔できいた。華やかなファッション写真家と決別した彼は、自分の人生を重ねるようにして、中国残留日本人孤児が訪日するたびに調査会場へ大型カメラを持ち込み、今年九〇年二月に祖国を訪れた第二十次の人びとまで、九年間にわたって肖像写真を撮りつづけた。

その間、身元が判明し肉親と対面できたのは六百六人で、実に六四パーセントの孤児たちは肉親の名乗りはなく、日本人としての名もわからず、出生の根を絶たれたままむなしく帰国した。『私は誰ですか』は、その人びとなのである。

四十代・五十代のどの顔も、肉親と別れた昭和二十年敗戦直後のあの場所あの瞬間に佇むようにして、ひたすら肉親をさがし悲しげにしかし希望にみちて、叫ぶのではなく静かに語りかけている。一時的なテレビ画面や新聞掲載の小さな写真とちがって、その表情に微細な特徴がとらえられ、歴史の忘却の時間を超えて生まなましい人間の姿で迫ってくる。

しかし、この写真集の出版は容易ではなかった。政府がつくって当然だと思うが、出版委員会が全国から費用を募り、なお不足ながらボランティアの協力で実現したという。この八月から全国の市町村役場などに置かれ、肉親さがしの「台帳」として誰もが見られるようになった。私が机上に置いて毎日対面してもその手助けにはならないけれども、引きよせられて頁をくってしまい、一人一人から眼を離すことができない。

胸の名札に「劉玉香」とある女性。髪がやや薄くなっている彼女は、右手に幼女の小さな写真をかかげ、白い歯をのぞかせて微笑みがちに立っている。訪日のために急いで新調したらしい黒っぽいスーツ姿だが、袖を五センチも折っているのは寸法が長すぎるからだろう。「二〇年八月時点での推定年齢 四歳。血液型 B型。離別した地点 北安省綴授県。離別した年月日二〇年一〇月頃、日本名=不明。家族構成=父、母、兄。父母、家族の職業 開拓団。家族といた頃の生活状況=不明。離別した時の状況、兄と思われる男の子の手を引いた母に背負われ、綏梭県の駅に近い養父劉春芳の家まで行き、預けられた。その時、青いチャンチャンコを着ていた。その後、母が七~八歳の男の子を連れて養家に来たが会えなかった」

記録はこれだけである。

残留孤児は満蒙開拓団として送り出された人びとの子供が多く、彼女もその一人だが、当時推定四歳の彼女は自分の日本名も両親の名も覚えていない。欄外に「手に持っている写真は九歳当時のもの」とあるから、養家で撮ったのだろう。古ぼけて色褪せ、手にしただけで粉々になってしまいそうに脆く小さいが、ふっくらとした頬の少女で、両親や兄が見れば「アッ、◯◯ちゃんだ!」と叫ぶ写真だ。そのあどけない面ざしが、五十歳に近い劉玉香さんの笑顔のなかから二重映しに浮かびあがってくる……。

譚永福さん。彼も黒っぽい上衣の袖を折っている。男物ではなく女性用の仕立てのようである。大陸の大地から顔をあげたような土臭い表情で、鼻下に薄く髭がのびている。敗戦時の推定年齢一歳の彼は、日本名、父母の職業、家族構成、家族といた時の生活状況、すべて「不明」とある。身体的特徴として「眉間にほくろが二つある」。「二一年一〇月、母が、吟爾浜市南崗木介街の養父母の家(ロシア風の建物)で、養母趨羨挙に預けた」 彼の記録もこれだけだ。幼児の頃の写真も手がかりになる品も何一つ持ってはいない。四十を幾つか過ぎた男が、年齢よりも老けた皺を刻み、節くれた手を垂れて緊張ぎみにカメラを見ている……。

思い出す。私自身のことをである。太平洋戦争の敗色が濃くなった昭和十九年九月、私は家族と近くの写真館に行き写真を撮った。国民学校五年生だった私は、東京の空襲を逃れ両親姉妹と別れて、東北の小さな町へ学童集団疎開をしたのだが、その数日前だった。二度と生きて会えぬかもしれないと両親は覚悟して、記念写真を撮ったのである。近所の人びとがみなそうしていた。幸い私の家族は翌年三月十日の東京大空襲に生きのび、敗戦後私は両親姉妹と再会できたが、戦災孤児になった友人は、そのときの写真を手がかりに両親の消息をたずねて、戦後しばらく焼跡をさまよった。

人生の特別の日に、緊張ぎみに正面をむいた一葉の写真。今日、誰もがカメラを持ち写真を撮る行為は日常茶飯事だけれども、特別の日の一見おもしろみのない肖像写真は、写真という芸術の原点といえる。自然な表情をさりげなくとらえた動きのある写真よりも、よそゆきでスタティクであるゆえにかえって、すぐには言葉にならぬ人生の言葉を深いところから静かに語りかけてくる。

この一千九十二人の肖像は、戦後四十五年をへて戦争の悲惨さがまだ終っていない長い歳月を刻みながら、「私は誰ですか」と人間としての存在証明を、肉親ばかりか戦争を忘れがちな日本人のすべてに求めている。九年間に及ぶ訪日調査が一区切りつき、残留孤児問題が報道から消えてゆくこれから、いっそうこの事実を忘却することはできない。

何も映っていない白い背景に、わが子として育てた中国人養父母や家族、その中国の山河、そして、まだ訪日できない孤児たちの父となり母となった姿も立ち上ってくる。肉親と再会させてあげたいが、ここにいる人びとの多くはおそらく、自己のルーツを証明できないまま中国人として生涯を終るかもしれない。わかっていても名乗り出ない肉親もいるという複雑な奥の深さを思えばなおさらに、その肖像は瞬間の表情でありながら終ることのない戦争の一生をそれぞれに語りかけてくる。私は座右の書として一生かかっても読みつくせないだろう。(了)

(新潮 1990年11月号・窓 さえしゅういち)

四十代・五十代のどの顔も、肉親と別れた昭和二十年敗戦直後のあの場所あの瞬間に佇むようにして、ひたすら肉親をさがし悲しげにしかし希望にみちて、叫ぶのではなく静かに語りかけている。一時的なテレビ画面や新聞掲載の小さな写真とちがって、その表情に微細な特徴がとらえられ、歴史の忘却の時間を超えて生まなましい人間の姿で迫ってくる。

しかし、この写真集の出版は容易ではなかった。政府がつくって当然だと思うが、出版委員会が全国から費用を募り、なお不足ながらボランティアの協力で実現したという。この八月から全国の市町村役場などに置かれ、肉親さがしの「台帳」として誰もが見られるようになった。私が机上に置いて毎日対面してもその手助けにはならないけれども、引きよせられて頁をくってしまい、一人一人から眼を離すことができない。

胸の名札に「劉玉香」とある女性。髪がやや薄くなっている彼女は、右手に幼女の小さな写真をかかげ、白い歯をのぞかせて微笑みがちに立っている。訪日のために急いで新調したらしい黒っぽいスーツ姿だが、袖を五センチも折っているのは寸法が長すぎるからだろう。「二〇年八月時点での推定年齢 四歳。血液型 B型。離別した地点 北安省綴授県。離別した年月日二〇年一〇月頃、日本名=不明。家族構成=父、母、兄。父母、家族の職業 開拓団。家族といた頃の生活状況=不明。離別した時の状況、兄と思われる男の子の手を引いた母に背負われ、綏梭県の駅に近い養父劉春芳の家まで行き、預けられた。その時、青いチャンチャンコを着ていた。その後、母が七~八歳の男の子を連れて養家に来たが会えなかった」

記録はこれだけである。

残留孤児は満蒙開拓団として送り出された人びとの子供が多く、彼女もその一人だが、当時推定四歳の彼女は自分の日本名も両親の名も覚えていない。欄外に「手に持っている写真は九歳当時のもの」とあるから、養家で撮ったのだろう。古ぼけて色褪せ、手にしただけで粉々になってしまいそうに脆く小さいが、ふっくらとした頬の少女で、両親や兄が見れば「アッ、◯◯ちゃんだ!」と叫ぶ写真だ。そのあどけない面ざしが、五十歳に近い劉玉香さんの笑顔のなかから二重映しに浮かびあがってくる……。

譚永福さん。彼も黒っぽい上衣の袖を折っている。男物ではなく女性用の仕立てのようである。大陸の大地から顔をあげたような土臭い表情で、鼻下に薄く髭がのびている。敗戦時の推定年齢一歳の彼は、日本名、父母の職業、家族構成、家族といた時の生活状況、すべて「不明」とある。身体的特徴として「眉間にほくろが二つある」。「二一年一〇月、母が、吟爾浜市南崗木介街の養父母の家(ロシア風の建物)で、養母趨羨挙に預けた」 彼の記録もこれだけだ。幼児の頃の写真も手がかりになる品も何一つ持ってはいない。四十を幾つか過ぎた男が、年齢よりも老けた皺を刻み、節くれた手を垂れて緊張ぎみにカメラを見ている……。

思い出す。私自身のことをである。太平洋戦争の敗色が濃くなった昭和十九年九月、私は家族と近くの写真館に行き写真を撮った。国民学校五年生だった私は、東京の空襲を逃れ両親姉妹と別れて、東北の小さな町へ学童集団疎開をしたのだが、その数日前だった。二度と生きて会えぬかもしれないと両親は覚悟して、記念写真を撮ったのである。近所の人びとがみなそうしていた。幸い私の家族は翌年三月十日の東京大空襲に生きのび、敗戦後私は両親姉妹と再会できたが、戦災孤児になった友人は、そのときの写真を手がかりに両親の消息をたずねて、戦後しばらく焼跡をさまよった。

人生の特別の日に、緊張ぎみに正面をむいた一葉の写真。今日、誰もがカメラを持ち写真を撮る行為は日常茶飯事だけれども、特別の日の一見おもしろみのない肖像写真は、写真という芸術の原点といえる。自然な表情をさりげなくとらえた動きのある写真よりも、よそゆきでスタティクであるゆえにかえって、すぐには言葉にならぬ人生の言葉を深いところから静かに語りかけてくる。

この一千九十二人の肖像は、戦後四十五年をへて戦争の悲惨さがまだ終っていない長い歳月を刻みながら、「私は誰ですか」と人間としての存在証明を、肉親ばかりか戦争を忘れがちな日本人のすべてに求めている。九年間に及ぶ訪日調査が一区切りつき、残留孤児問題が報道から消えてゆくこれから、いっそうこの事実を忘却することはできない。

何も映っていない白い背景に、わが子として育てた中国人養父母や家族、その中国の山河、そして、まだ訪日できない孤児たちの父となり母となった姿も立ち上ってくる。肉親と再会させてあげたいが、ここにいる人びとの多くはおそらく、自己のルーツを証明できないまま中国人として生涯を終るかもしれない。わかっていても名乗り出ない肉親もいるという複雑な奥の深さを思えばなおさらに、その肖像は瞬間の表情でありながら終ることのない戦争の一生をそれぞれに語りかけてくる。私は座右の書として一生かかっても読みつくせないだろう。(了)

(新潮 1990年11月号・窓 さえしゅういち)